When I meet Kenny Belov mid-morning at San Francisco’s Fisherman’s Wharf, the boats that would normally be out at sea chasing salmon sit tethered to their docks. The steady breeze coursing through the bay belies choppier conditions farther out—so rough that the local fishermen threw in the towel for the fifth morning in a row. Belov scans the horizon as he explains this, feet away from the warehouse of his sustainable seafood company, TwoXSea. Because his business hinges on what local fishermen can bring in, he’s used to coping with wild fish shortages.

But unlike these fishermen, Belov has a stash of treasure in his warehouse, as he soon shows me: a golf-cart-size container of plump trout, their glossy bodies still taut from rigor mortis. The night before, Belov drove north to Humboldt to help “chill kill” the fish by submerging them live into barrels of slushy ice water. Belov can count on shipments of these McFarland Springs trout every week—because he helped grow them himself on a farm.

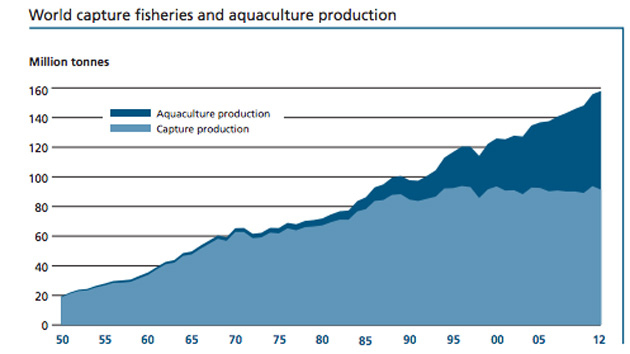

For many consumers, aquaculture lost its appeal after unappetizing news spread about commercial fish farms—like fish feed’s pressure on wild resources, overflowing waste, toxic buildup in the water, and displacement of natural species. But consider this: Our appetite for seafood continues to rise. Globally, we’ve hungered for 3.2 percent more seafood every year for the last five decades, double the rate of our population. Yet more than four-fifths of the world’s wild fisheries are overexploited or fully exploited (yielding the most fish possible with no expected room for growth). Only 3 percent of stocks are considered underexploited—meaning they have any significant room for expansion. If we continue to fish at the current pace, some scientists predict we’ll be facing oceans devoid of edible marine creatures by 2050.

Aquaculture could come to the rescue. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations predicts that farmed fish will soon surpass wild-caught; by 2030, aquaculture may produce more than 60 percent of fish we consume as food.

One of the most pressing concerns about aquaculture, though, is that many farmed fish are raised on a diet of 15 million tons a year of smaller bait fish—species like anchovies and menhaden. These bait—also known as forage fish—are ground up and converted into a substance called fishmeal. It takes roughly five pounds of them to produce one pound of farmed salmon. Bait fish are also used for nonfood products like pet food, makeup, farm animal feed, and fish oil supplements.

It may appear as though the ocean enjoys endless schools of these tiny fish, but they too have been mismanaged, and their populations are prone to collapse. They’re a “finite resource that’s been fully utilized,” says Mike Rust of NOAA’s fisheries arm. Which is disturbing, considering that researchers like those at Oceana argue that forage fish may play an outsize role in maintaining the ocean’s ecological balance, including by contributing to the abundance of bigger predatory fish.

And that’s where Belov’s trout come in: Though he swears no one can taste the difference, his fish are vegetarians. That means those five pounds of forage fish can rest easy at sea. It also means that the trout don’t consume some of the other rendered animal proteins in normal fishmeal pellets: bone meal, feather meal, blood meal, and chicken byproducts.

Belov and McFarland Springs’ owner David McFarland were inspired to switch to vegetarian feed in part by Rick Barrows, a USDA researcher. About six years ago, recounts Barrows, several USDA studies confirmed that fish rely on nutrients—vitamins, minerals, fatty acids, and protein—rather than fishmeal or fish oil, to thrive. If those nutrients could be found in other products, including purely plant-based substances, then aquaculture might not be so dependent on feeding fish other smaller fish.

Barrows and team began to test about 50 potential materials a year, and now have a database of 140 that anyone can browse through online. Belov was one of their first commercial partners. The plant-based food fed to McFarland Springs’ trout consists of a hearty blend of marine algae, freshwater micro algae, vitamins, minerals, flax, flax oil, corn, and nut waste. The resulting complete protein means the trout’s omega 3s are high and their omega 6s are low—a ratio that’s said to enhance anti-inflammatory properties. And “they don’t have the concentration of heavy metals that come from the bait fish,” Belov says. I took one of his rosy fillets home and turned it into trout lox; find the recipe here.

McFarland Springs manages the trout’s waste by funneling it out into a natural sagebrush pasture where it composts the soil.

Barrows thinks region-specific material for this type of feed offers the most potential. For instance, his team learned that around 5 percent of California nuts can’t be sold because they’re broken or disfigured. They realized they could repurpose excess nut parts for the trout feed; the nut bits helped round out the complete protein. Lately, Barrows has become especially excited about turning barley surplus from the beer industry—which comes at a cheap price in Montana, where he’s based—into a feed-grade concentrate for trout feed.

“You can get just as much growth rate out of fishmeal-free feeds as fishmeal,” says Barrows. And his lab has proven as much with eight different fish species: cobia, Florida pompano, coho salmon, Atlantic salmon, walleye, yellowtail, and White seabass.

But the price difference still stands in the way for many fish farmers. Belov pays slightly more than $1/pound for his plant-based feed, whereas fishmeal pellets average around $0.71/pound. He sells his trout for $6.95/pound, about a dollar more than conventional. But he’s well positioned in the affluent Bay Area, and he usually sells out of his McFarland Springs trout well before the end of each week. As innovation continues in the realm of plant-based feeds, he’s hopeful, along with Barrows, that the price of the pellets will continue to drop.

Here in the United States, we consume plenty of farmed fish already, but only 5 percent of it is sourced domestically. “If we didn’t import so much farmed seafood,” implored Four Fish author Paul Greenberg in a recent New York Times op-ed, “we might develop a viable, sustainable aquaculture sector of our own.” It doesn’t just boil down to economics: The locations we generally export from, like China and South Asia, don’t have near the stringent environmental and health regulations as the US. “Growing more seafood at home would help with trade deficit, but also we could control the safety more,” says Barrows.

Though our current aquaculture sector is relatively tiny, US farmers are in a better position to innovate, because we have a sophisticated animal nutrition research center and feed sector, says NOAA’s Rust. “We’re the leading technical country in the world on feed.”

Belov wasn’t always open to aquaculture, and he still feels that fish—such as some salmon—with healthy wild fisheries attached to them should never be farmed. That way, environmentally responsible fishermen can stay in business. His long-term strategy for sustainable seafood? Draw from the “amazing [wild] fisheries that exist, and then you backfill with intelligent aquaculture, and yes, you can feed the planet with sustainable marine products.” Which may take more work, but as he puts it, “We depleted the ocean. It wasn’t anybody else’s fault. So it’s our job to fix it.”