Mmm... <a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-83572729/stock-photo-fresh-fish-fingers-with-potatoes-and-remoulade-sauce.html?src=xaJu5tAkLLV5FFwzMyEd9A-1-1">CGissemann</a>/Shutterstock

Many people think of climate change as something happening in the atmosphere, but a lot of the most important changes are taking place under the ocean.

In fact, up to one-third of the greenhouse gases humans release, and up to 90 percent of the global warming caused by those gases, ends up sunken in the sea. That has a lot of scary consequences: A rising sea level threatens coastal communities; rising seawater acidity kills off coral and shellfish; and changing conditions are forcing dozens of species, from whales to puffins, into unfamiliar regions of the globe. We’ve even got cannibal lobsters, for crying out loud.

Those impacts can also devastate vital US industries, as a peer-reviewed study published today in Nature illustrates. The research found that warming waters are to blame for a recent collapse of the cod fishery in New England. Although a smaller industry than major commercial fish like salmon and mackerel, cod, commonly used for fish sticks and other processed foods, is a multimillion-dollar business in New England.

But the fish have become increasingly rare. Last year, federal regulators slapped tight limits on cod fishing after they discovered that the population was at only 4 percent of the level needed to be sustainable. That was the lowest point in a nosedive that has played out over the last decade. In 2014, the commercial catch of cod in New England—about 5 million pounds—was 67 percent less than it was in 2004; the net value of the fishery was correspondingly cut by more than half, to about $9.3 million.

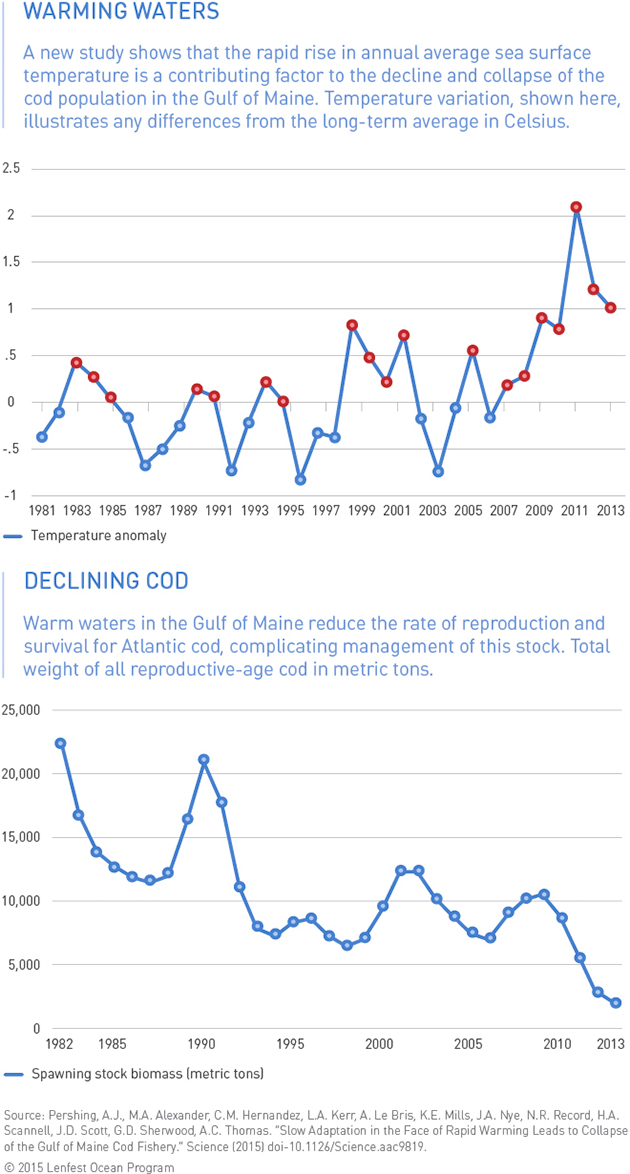

Researchers at the Gulf of Maine Research Institute wanted to know whether climate change played a role in that collapse. Indeed, they found that sea surface temperatures in the Gulf of Maine have risen 99 percent faster than those in the rest of the ocean, increasing especially quickly over the same decade-long decline of the cod fishery. The correlation is clear when you look at the two trend lines side by side, as in this chart from the study:

Higher temperatures make it harder for the fish to metabolize food, leaving them with less energy, especially at their prime reproductive age of about four years. That leads to fewer fish being born. Those that are born may have a harder time finding food, as the plankton they survive on move into deeper water in search of cooler temperatures. Deep water is home to more cod predators.

These problems have all been compounded by a lack of climate-savvy policy by fishing officials, the study found. Because the officials have largely overlooked the impact of ocean warming, they’ve consistently set quotas for commercial fishers far too high, giving the cod population no opportunity to rebound even in cooler years. In other words, overfishing has been rampant even when the overall catch comes in below the legally prescribed limit.

For that reason, the key solution that the researchers advocate is better integration of climate modeling in decisions about where, when, and how cod fishing should be allowed. In Canada, extreme limitations on cod fishing seem to have been remarkably successful in revitalizing the population. Still, those management choices aren’t getting any easier to make, as warming continues to rise; the only true fix for New England’s fishing industry is to slow the warming. Bear that in mind the next time you hear a politician complain about job-killing climate action policies.