Central Valley cities like Fresno have struggled with air pollution for decades.Gary Kazanjian/AP

This story was originally published by City Lab and appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Kieshaun White says that he doesn’t like to talk politics when it comes to the environment. He prefers to stick to the data.

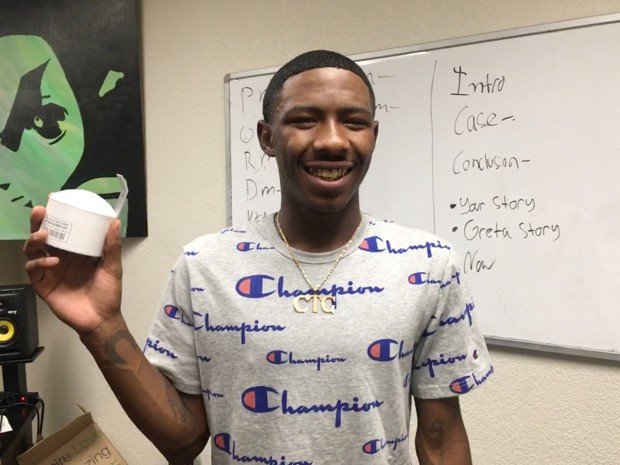

A year ago, as a high school senior, he launched a network of air-pollution sensors and real-time app to monitor breathability around his native Fresno. White founded Healthy Fresno Air, using grant funds from the city’s Boys and Men of Color group, which was recently awarded $50,000 by former President Barack Obama’s My Brother’s Keeper initiative.

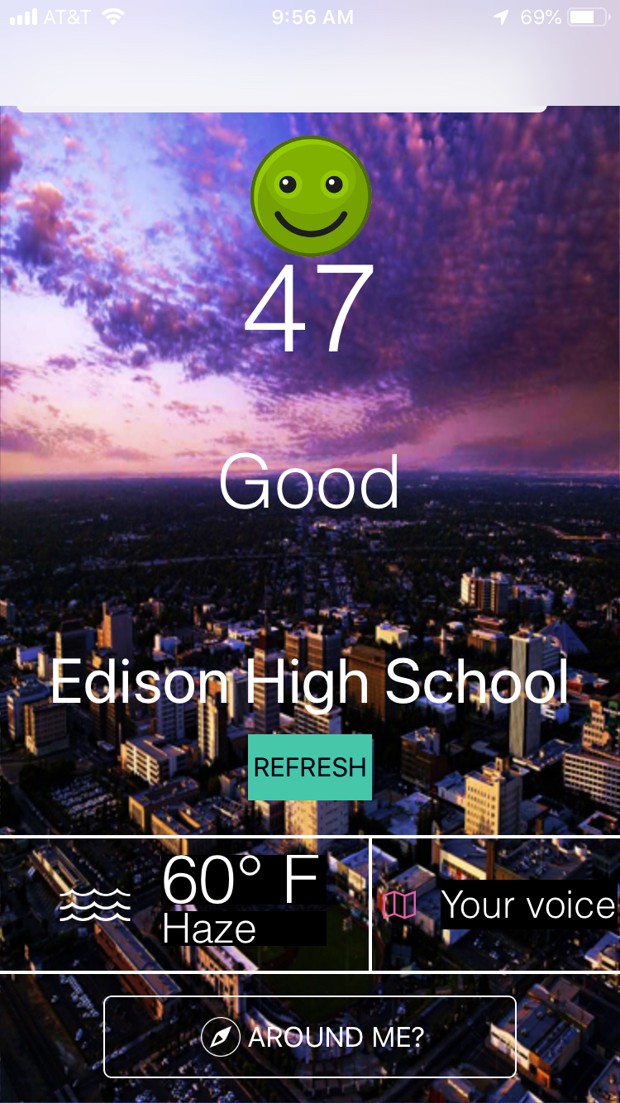

Kieshaun White’s air quality app shows pollution levels around the city in real time.

Healthy Fresno Air

At first, he deployed a handful of monitors at high schools on Fresno’s heavily polluted southwest side; since then, he has expanded the network to other quadrants of the city. This spring, he launched a public-facing app that shows real-time information gathered by the sensors about levels of PM 2.5 and PM 10—the fine particulate matter (PM) that blow off freeways and smokestacks and into mouths and noses.

Kieshaun White displays an air monitor from his Healthy Fresno Air project.

Laura Bliss/CityLab

The San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District headquarters in Fresno, seen on a September day that was rated unhealthy for sensitive groups.

Laura Bliss/CityLab

Apart from rampant respiratory disease, Valley residents also suffer from elevated rates of heart disease and stroke. Many health factors contribute to the high health risk, including widespread poverty and an economy that relies on low-paid hard labor. But air quality plays a large role. Fresno lies in the heart of the San Joaquin Valley air basin, a 250-mile-long bowl classified by the EPA as an “extreme non-attainment area.” For 30 years, the region has fallen far short of federal air quality standards, both in terms of ozone (commonly known as smog) and fine particulate matter.Especially lethal is PM 2.5., a tiny particulate that can move from the lungs into blood stream, constricting blood flows to the heart and brain. On days of elevated 2.5, hospitals see more heart attacks and strokes, said Genevieve Gale, the director of the Central Valley Air Quality Coalition, a nonprofit advocating for cleaner air. (Between 2015 and 2017, Fresno had nearly 250 days that were rated “unhealthy” by the American Lung Association.)

“This is arguably the most polluted air basin in the US,” said Gale. “And with a combination of vulnerable people and bad reactions, it’s a public health crisis.”

Further motivating White to take action on air quality issues—what got him “inflamed,” to use his word—was the huge disparity in health outcomes. Average life expectancy in his largely black and Latino community in southwest Fresno is about two decades less than in whiter, wealthier enclaves to the north. And his data has shown that the air is four times worse where he grew up, thanks to clusters of industry and highway interchanges. “I don’t want to die 25 years too soon,” White said.

The region’s pollution problems emerge from a toxic mix of human activity and natural topography. Heavy truck traffic going up and down the state’s inland freeways and agricultural machinery contribute a share of smog and particulates; so do wood-burning stoves, crop fires, and oil and gas extraction by the likes of Chevron, which drills across the land. Pollution from the Bay Area and Sacramento Valley can also waft its way south, sometimes joined by wildfire smoke from the nearby Sierras. Ringed by mountain ranges, the San Joaquin Valley is prone to temperature inversions that trap these pollutants, especially through hot summers and foggy winters.

The failure to comply with federal air quality standards isn’t for lack of trying, said Samir Shiekh, executive director and air pollution control officer at the San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District, the agency charged with regulating stationary sources of pollution for the region. “There are a lot of factors that have always made it more difficult than nearly any other area to bring ourselves into attainment of federal and state standards,” he said. “But there’s a positive story here.”

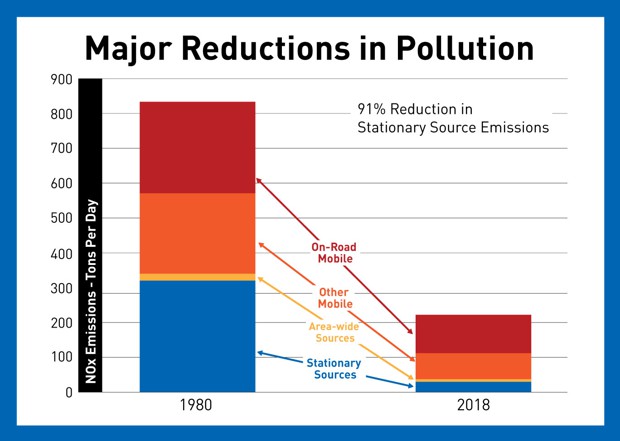

By issuing permits to businesses, requiring special vehicle registration fees, and investing billions of dollars in clean energy, waste processing, and vehicle fleet, the agency has measurably improved air quality since it began gathering data in 1980. Industry and agriculture used to be the primary sources of emissions in the Valley; today, both of those sectors now represent a fraction of the overall pollution. Now, the biggest source is from transportation.

There is much more to be done in order to come into compliance, said Sheikh. Recent strides include tighter rules on wood-burning fires and the release of two enormous community-led plans to reduce pollution in south Fresno and Shafter, a heavily polluted city in neighboring Kern County.

On the other hand, there’s also only so much that Shiekh’s agency has control over. Regulating tailpipe emissions and other “mobile” sources of pollution is the jurisdiction of CARB, which was formed in 1967 to help the state rein in its notorious vehicle smog. Now the Trump administration is in the process of undoing the strict fuel economy rules set by that agency. This puts the Valley in peril of getting hit with serious sanctions from the EPA, said Shiekh, since the region would still be held to the same high federal air quality standards without the state’s help in reducing smog and gas that doesn’t come from local emitters.

“The vast majority of our remaining air pollution challenge comes from those mobile sources,” he said. “Even if we were to shut down all of the stationary sources under our jurisdiction, that wouldn’t be enough to bring the Valley into compliance with the federal standards.”

Gale put it more bluntly. “Taking away tools from California to attain those standards is really dangerous,” she said. “We’ve been so far behind for so long that any additional time you add to the clock takes years off of people’s lives.”

In that sense, the federal government’s assault on California air quality rules appear to be the latest example of how White House policy directly harms some of the same people who voted for the president. (See also: the ongoing tariff war that is hurting some farmer livelihoods.) California may be a dependably progressive state, but much of the San Joaquin Valley votes Republican, and some of Trump’s closest allies in Congress represent the region. Kevin McCarthy, the House Minority Leader, hails from a district in neighboring Kern County; Devin Nunes’s district encompasses the Fresno suburb of Clovis.

The San Joaquin Valley Air Basin may not be in federal attainment, but it has made major progress in reducing emissions since 1980.

San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District

Aides for McCarthy did not respond to CityLab’s requests for comment; nor did those of Nunes. Jim Costa, the Democratic congressman who represents most of the city of Fresno, has condemned the Trump administration’s move. McCarthy has stated that he believes that a single emissions standard would be better for the state. “When you set emissions numbers that people can’t reach, and you aren’t taking economics into play… we could have one emission for everyone, and everybody would be happy,” he said in a 2018 interview with the Public Policy Institute of California.

For White, the political volleying feels like a dismaying waste of time. To him, the stakes are higher than Fresno’s bad air: White also organized Fresno’s local climate strike, leading youth marchers through downtown streets to call on leaders to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions that are warming the planet. They chanted lines that he came up with: We walk as one, we breathe as one, we’re not going to stop ‘til the work is done. In an upcoming march, White plans to brandish signs asking Costa to pledge support for the Green New Deal.

After all, election results don’t always fully represent what people need or want. The San Joaquin Valley has some of the lowest voter turnout in the state. In White’s neighborhood, people feel disempowered, he said. He hopes his work will change that. Right now, he’s working with city officials to install an air quality monitor in each of the 115 square miles that make up Fresno, which will make his platform more accurate and useful. And he’s building a database that anyone can use to find air quality information. “We want to give this data to the community and let them press it to decision-makers,” White said.

And now that he’s 19, White intends to vote for leaders who care about the planet—and encourage his neighbors to do the same. “People in the southwest area of Fresno think their voices don’t matter,” he said. “But if we vote en masse, it’ll show a difference.”