Kate Sheppard is reporting this week from Vietnam, where she’s learning how the country is already adapting to climate change. To read her first dispatch—from a farm where one family is planting a new type of watermelons designed to withstand weird weather caused by global warming, click here.

The disappearing coastline is one of the most oft-cited concerns about climate change, as rising sea levels gradually chip away at the edge of our terrestrial domain. In Vietnam, that’s certainly a concern, with 2,025 miles of exposed coastline. But more immediately, the rising seas are pushing salty water into freshwater sources like the mighty Mekong River.

The delta is the region of southern Vietnam were the branches of the river reach the sea. Known here as the “Nine Dragons” of the Mekong, the tributaries pass through fertile farmland before emptying into the sea. Salinity intrusion has long been a problem, but as the sea level rises, the salty waters of the South China Sea are traveling farther up the long fingers of the Mekong. The salt poses an immediate threat to much of the agriculture here: rice, coconuts, and other crops. It’s also making it harder for people who live here to access freshwater for drinking, cooking, and bathing.

This is a particular challenge in Vietnam’s Ben Tre province, whose land lies between four of the Mekong’s dragons. I visited Ben Tre, a sleepy coastal province about two hours from Ho Chi Minh City, as part of a field trip for the Community-Based Adaptation Conference taking place in Vietnam this week. Ben Tre is the most affected of the country’s provinces in terms of sea level rise, with 50 percent of its land area expected to be submerged by 2100 with one meter of sea level rise (which is within the range of what scientists predict will occur). But saltwater intrusion is already a major problem, and local officials say that the brackish water is creeping as much as five kilometers farther up the river each year. (It’s also exacerbated by decreased flow down the Mekong from big dams upstream, and by more severe dry seasons that mean less fresh water flowing through.)

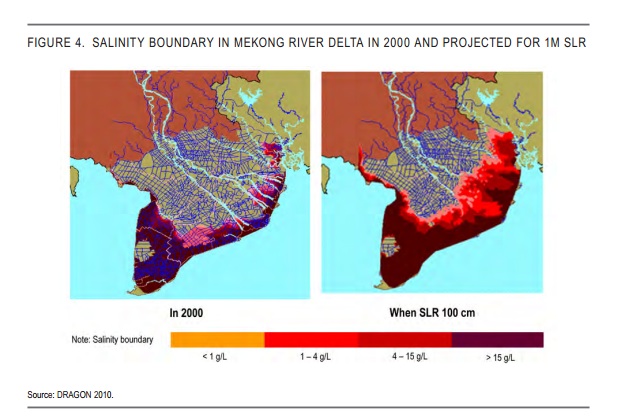

It’s not just in Ben Tre. Here’s the projection for salinity intrusion throughout the Mekong Delta from climate researchers at Can Tho University’s DRAGON Institute:

DRAGON Institute/World Bank

DRAGON Institute/World Bank

Home to 1.3 million people, Ben Tre has nearly tripled its GDP in recent decades by increasing agricultural and shrimp exports, and boasts that it’s the “coconut capitol” of Vietnam. But access to freshwater is crucial to continued development here, and getting that water is getting really difficult.

This is one reason the Vietnamese government has made Ben Tre a pilot site for a National Target Program to Respond to Climate Change. The first projects have included building a dam and a sluice gate to protect freshwater in the region. Earlier this week, I went out to see the earthen dam in the Thanh Tri commune that now closes off a branch of the river so that salt water can’t enter. To get out to this part of the country, we crossed over five smaller fingers off the river, rumbling over five tiny one-lane bridges.

The dam was started in 2010 and completed a year later. Now, on one side shrimpers and farmers load up large boats with goods for transport. On the other, coconut trees grow along the freshwater. Atop the dam, a few locals are repairing small wooden boats used to navigate the tributaries and channels. The province also built a large sluice gate on another branch of the Mekong to prevent saline intrusion back in 2002.

The newest dam might seem underwhelming; after all, who hasn’t seen a dam before, and this one is really just a pile of dirt. But they’re significant for several reasons. For one, it’s expensive to build a dam. This project was paid for with part of a $25 million grant from the Danish government, which is also providing technical support for the province. And for two, it’s kind of a big deal to dam off open access to a waterway—a permanent testament to the fact that the Vietnamese government doesn’t think this problem is getting any better any time soon.

A pile of coconuts beside the new dam Kate Sheppard

A pile of coconuts beside the new dam Kate Sheppard