A white-crowned sparrow whistles. yhelfman/iStock

As spring approaches, US farmers are gearing up to plant about 180 million acres in corn and soybeans—a combined land mass nearly twice the size of California, mostly in the Midwest. The great majority of the seeds they sow will be coated with neonicotinoid pesticides: synthetic chemicals thought to be harmless to humans but that attack bugs’ central nervous systems—and, as new research shows, hinder birds’ navigation abilities.

Neonics, as they’re known, are the globe’s most widely used class of insecticide, representing a multi-billion-dollar market for their primary makers, the agrichemical giants Bayer and Syngenta. Meanwhile, a growing body of research suggests they harm pollinators like bees, birds, and water-borne insects (a major food source for birds and fish). The European Union has maintained a moratorium on several neonic uses since 2013.

Here’s a collection of the latest research on the ecological effects of these widely used farm chemicals:

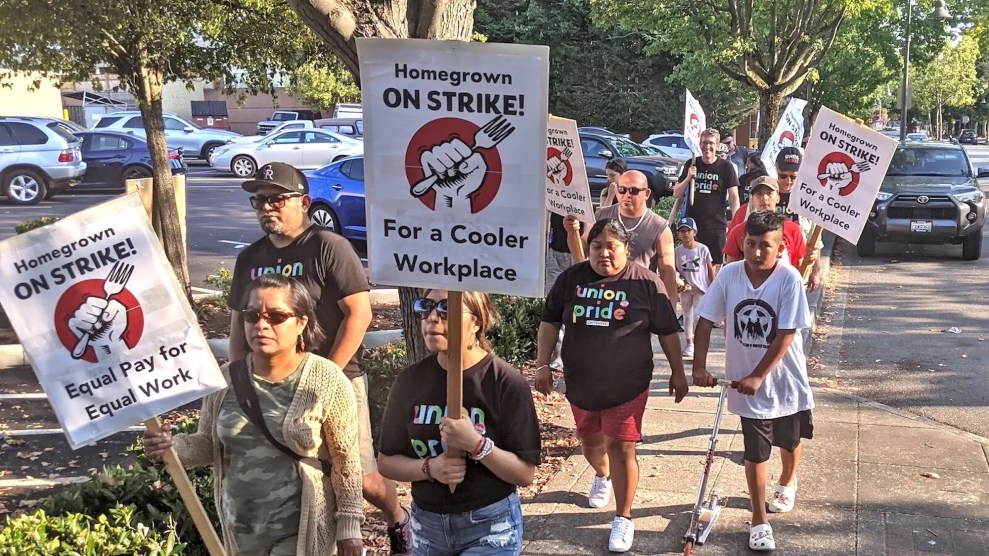

• Neonics may impair bird migrations. Lots of bird species scavenge seeds for their meals. And these days, many of those seeds are coated in neonics. In a study published last fall, Canadian researchers dosed white-crowned sparrows—a seed-eating, migrating songbird—with the insecticides at various levels. They found that just four seeds coated with imidacloprid, consumed over three days, was enough to cause “significant declines in fat stores and body mass” in the bird and a reduced ability to navigate.

The tendency of neonics to end up in water is also bad news for birds. In a great Audubon magazine piece from last year, Elizabeth Royte profiles one of the authors of the sparrows study, Christy Morrissey, a wildlife ecotoxicologist at the University of Saskatchewan. She tells Royte that only about 5 percent of the neonics in seed coatings are taken up by the plant. The rest, Royte writes, “leaches off the seed, accumulates in soil, and sluices via snowmelt, rain, and groundwater seepage into ponds and wetlands, where insects like midges and caddis flies—a staple for billions of grassland birds—start their lives.”

• They are all over the Great Lakes, the “world’s largest freshwater ecosystem.” For a paper published this year, researchers from the US Environmental Protection Agency and the US Geological Survey tested water entering the Great Lakes through 10 major tributaries for a year, starting in October 2015. They found traces of at least one neonic in 74 percent of the monthly samples, and at least three in 10 percent. “Neonicotinoid concentrations generally increased in spring through summer coinciding with the planting of neonicotinoid-treated seeds,” the researchers found.

The chemicals typically showed up at levels beneath the threshold known to kill water-dwelling creatures outright. But, the researchers warned, concentrations rose in the spring and summer months, a time when many aquatic species are at a “sensitive stage of development.” And they note that even at low levels, “near-constant neonicotinoid exposure” can cause subtle, long-term damage to aquatic ecosystems, as shown by this 2016 paper reviewed by a researcher from Environment Canada, our northern neighbor’s version of the EPA.

• They are terrible for bees. A series of devastating papers published in Science magazine last year showed just how harmful neonics are to the pollinators that are essential to the fresh fruits and vegetables we grow. In one, a team of Swiss researchers found traces of the chemicals in 75 percent of honey samples drawn from around the world—and 86 percent of the samples from North America. In another, published last June and funded by Syngenta and Bayer (and later hotly contested by them), UK, German, and Hungarian researchers found that neonicotinoids cause a “reduced capacity” of both wild and honey bee species to “establish new populations in the year following exposure.” Yet a third Science paper showed that bee hives kept near corn fields are constantly exposed to neonics during the growing season, causing “increased worker mortality” and “declines in social immunity and increased queenlessness over time.”

• And they’re not even very effective against crop pests. Neonics aren’t worth all of the potential damage to bees, birds, and aquatic animals they appear to be causing, argues a new paper reviewing previous research. The chemicals don’t appear to boost crop yields for farmers who use them. That assessment is consistent with 2017 paper from Purdue University researchers, which found “no benefit of the insecticidal seed treatments in terms of crop yield” to US corn growers. (That study also found that when farmers plant treated seeds, surrounding bees are routinely exposed to harmful levels of “neonicotinoid dust drift.”) Then there’s this 2014 paper by EPA scientists and economists, which revealed that for US soybean farmers, “most usage of neonicotinoid seed treatments does not protect soybean yield any better than doing no with pest control.”

Giving these findings, might the Environmental Protection Agency consider reining in use of these troublesome and ubiquitous chemicals? After all, the agency has been engaged in a slow-motion review of them since 2008, a process it claims it will complete by 2019. But Aimée Code, the pesticide program director for the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation, says the EPA has a “has a pretty high tolerance for risk” when it comes to assessing whether to restrict pesticides; it will tolerate ecological damage if it’s offset by enough economic benefit. That tendency is only amplified by the anti-regulatory zeal of Scott Pruitt, the current EPA chief, who was recently profiled by Mother Jones’ Rebecca Leber. As a result, “we are unlikely to see meaningful changes to how neonicotinoids are regulated under the current federal administration,” Code says.