For nearly 30 years, the Reel M Inn has occupied a squat, stucco building on a corner along Southeast Division Street in Portland, Oregon. Sleek condos and coffee shops have erased most of the neighborhood’s blue-collar grit, but the Reel, as locals call it, remains the same: a classic dive bar with neon signs and fishing knickknacks layered on its dark-paneled walls. Until closing time at 2:30 a.m., bartenders serve pop-tops and shots from behind the narrow wooden bar—“Bloody Marys are about as fancy as it gets,” Carey Bolton, the Reel’s manager and co-owner, tells me. The tiny kitchen churns out fried chicken and jojos (potato wedges)—and pretty much only chicken and jojos—for 16 hours a day, 365 days a year. The wait for food can run up to two hours, but the clientele doesn’t seem to mind. The most devoted regulars are the dishwashers, cooks, and waitstaff from the high-profile restaurant row that turned the neighborhood into a foodie mecca. “We end up being a place that feeds the restaurant world in Portland,” says Alex Briggs, the Reel’s other co-owner and Bolton’s husband.

Briggs, a Portland native with a low voice and an even lower tolerance for bullshit, grew up just four blocks from the Reel. “I thought of it as this walled-off, windowless bar with a cool neon sign my middle school teachers went to for a drink after school,” he says. Once he got a fake ID, he started going there, too. Bolton, warm and equally no-nonsense, grew up in British Columbia and began her career in the restaurant industry as a teenage dishwasher. In 2014, following a move to Portland, Bolton became manager of the Reel, where she met Briggs. They got married and, in 2018, they bought the bar. “It took everything in us to purchase this place,” Briggs tells me. In 2019, business boomed, and the Reel closed for only two days: one for equipment failure, the other for a staff picnic. But as the coronavirus pandemic took root, neighboring restaurants shut down, and the Reel ended up closing for 77 days in 2020, and 88 in 2021. Even when open, it hobbled along on takeout and a few outdoor tables in between Portland’s rainy spells. “At every turn—as creative as you wanted to be—there’s still so many things tying your hands behind your back,” Briggs says. “It’s just like a Sisyphean task to try to even make sense of how you can possibly survive.”

There are half a million small independent restaurants and bars like the Reel. They account for three-quarters of all the country’s eating and drinking establishments and employ roughly 11 million people. To operate a restaurant under ordinary circumstances is a perilous endeavor. To operate during a pandemic proved nearly impossible. Thousands of independents are among the estimated 90,000 restaurants that have closed since March 2020, a year in which 2.5 million restaurant workers lost their jobs.

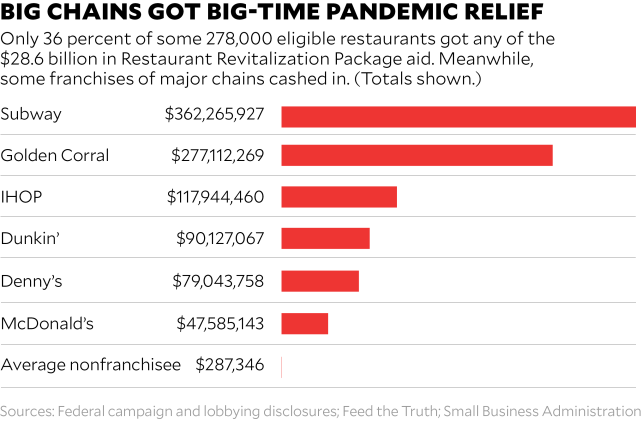

But while the Reel and fellow neighborhood joints limped by during the last two years—if they were able to stay open at all—a different story emerged for corporate restaurants. National chains like Applebee’s, P.F. Chang’s, Ruby Tuesday, and TGI Fridays all received federal loans between $5 million and $10 million from the first pandemic relief package Congress passed in March 2020. Thousands of Subway, Dunkin’, and McDonald’s franchises received that funding, too—and more cash again from the dedicated $28.6 billion in restaurant relief that passed in March 2021. By the end of 2020, financial experts raised stock expectations for major chains such as Darden (parent of Olive Garden) and Bloomin’ Brands (parent of Outback Steakhouse), which thrived by quickly pivoting to online ordering and delivery-friendly menus. One industry analysis spoke promisingly of steakhouse chain Texas Roadhouse, citing “industry closure activity, shouldered mostly by independent restaurants,” as a chance for the corporation “to expand its footprint into smaller markets.”

That independent restaurants struggled while big chains flourished wasn’t an inevitable outcome. Behind this dynamic was a force that has fiercely protected the industry’s Goliaths: the National Restaurant Association. On one level, the NRA is simply another trade association that lobbies on behalf of an industry and provides education and legal support to its members. In practice, it has bent federal, state, and local governments to the will of the corporate behemoths, claiming to represent the nation’s 500,000 food service establishments, even though less than 10 percent are members. Its critics call it “the other NRA”—an acronym the association avoids and almost never employs, but one that paints the group as comparable to the National Rifle Association, a trade group so enmeshed in corporate and GOP interests that it hardly represents the desires of most gun owners. Celebrity restaurateur Tom Colicchio described it with more diplomacy: “The [National Restaurant Association], I think, is conflicted—representing full independents but also representing the chains,” he tells me. “It’s kind of hard to do.”

For its part, the organization considers its mission unambiguous and expansive. “The National Restaurant Association is the voice of the restaurant industry,” a spokesperson for the group writes in a statement. “We represent and advocate for every restaurant at the federal, state, and local levels of government.” The spokesperson adds, “To say that the National Restaurant Association only represents chains is false.”

As the pandemic raged, tension inherent in the NRA’s mission gave way to open warfare as the industry cracked along the fault lines that the NRA long sought to obscure. New voices ascended to challenge the association’s power, and even succeeded to some degree. But as the crisis enters its third year, the NRA continues to guard the interests of its large corporate members while neighborhood diners and taverns wonder whether they’re about to serve their last meal.

The now-mighty trade group has humble roots. In 1916, Kansas restaurant owners banded together to block local farmers from raising the price of eggs, which then dropped from 65 cents to 32 cents. Thus, the nation’s nascent restaurant consortium notched its first win. Three years later, at the National Restaurant Association’s inaugural convention, 200 owners from across the country pledged to tamp down another potential drain on profits: organized labor.

Union hostility aside, the trade group spent its first several decades primarily as a booster organization that helped transform restaurants’ images from “greasy spoon” lunch counters to elegant, family-friendly establishments. In the 1930s, it ran ads urging married men to “Take Her Out to Dinner at Least Once a Week.” A 1950s campaign told Americans to “Enjoy Life—Eat Out More Often,” and pictured happy families seated together in dining booths.

The evolution into political juggernaut began amid a vicious partisan fight over President Bill Clinton’s ill-fated health care plan. During a 1994 town hall in Kansas City, Missouri, Godfather’s Pizza CEO Herman Cain challenged the president on the cost of mandating employer-based coverage. “On behalf of all of those business owners that are in a situation similar to mine,” Cain asked, “my question is, quite simply, if I’m forced to do this, what will I tell those people whose jobs I will have to eliminate?” Clinton rejected the causality, but Cain pressed on, arguing he’d have to pass increased costs on to customers and, in turn, lose business to even bigger chains that could more easily absorb the expense. Conservatives hailed Cain as a hero. Soon thereafter, Jack Kemp, the former NFL star and 1996 vice presidential candidate, traveled to Cain’s Omaha home to meet him, and convinced him to advise the Dole–Kemp presidential campaign.

The episode not only dealt another blow to the prospects of health care reform, but it also tied the NRA’s fate to that of the Republican Party. In 1996, Cain became CEO of the NRA and further strengthened its clout. As Congress weighed lowering the legal blood alcohol content limit for drunk driving, the association balked, arguing that such a change would hurt restaurant liquor sales. Its members similarly testified against federal indoor smoking bans. But its most significant legacy was quashing efforts to raise the minimum wage and offer paid sick leave to employees.

Holding down the cost of labor became the association’s raison d’être. In 1996, Cain led the charge to defeat an effort to raise the subminimum wage, which allows restaurants to pay servers less than the actual federal minimum wage because, in theory, they make up the difference in tips. A legacy of Jim Crow, the tipped minimum had been tethered to the higher federal minimum wage, but Cain and allies claimed that a higher tipped minimum would increase both unemployment and inflation—at a time when both were at their lowest since World War II. He succeeded in getting the two wages delinked. The subminimum wage, only $2.13 an hour in 18 states and still under $7.25 in nine more, hasn’t budged since.

Attempts to raise it on the local level have met a similar fate at the hands of the NRA’s affiliated state groups, which receive policy and advocacy training from the national group. When Washington, DC, held a vote on a ballot measure to eliminate the subminimum tipped wage in 2018, the NRA gave more than $70,000 to Save Our Tips, an astroturf campaign that convinced bartenders and servers that such a ban would hurt their bottom lines. The ballot measure passed, but DC’s city council later reversed it, thanks to pressure from the NRA. The Illinois Restaurant Association killed Chicago’s efforts to raise the minimum wage to $15 and eliminate the subminimum wage—even though Mayor Lori Lightfoot had won the election promising to do so.

When Democrats made similar attempts in the Covid relief package earlier last year, the NRA killed the measure and all but obliterated it from the Democratic agenda. They argued these “increased workforce costs are particularly difficult for independent owners to manage” and “the elimination of the tip credit would hurt millions of servers who rely on the current system where they earn between $19-$25 an hour with tips.” Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.) assured me in November that raising the wage was “absolutely something we’re going to do before the end of the year, because it’s one of our highest priorities as a caucus.” But Congress left Washington in December without breathing a word about it, a testament to the durability of Cain’s vision.

The CEOs after Cain have been cut from a similar corporate cloth. Marvin Irby, the NRA’s longtime chief financial officer and current interim CEO, did stints at Disney and Kraft Foods. He replaced Tom Bené, who was previously the CEO of Sysco and spent 23 years ascending the corporate ladder at PepsiCo. Dawn Sweeney, who helmed the group for 12 years starting in 2007, now works at a Connecticut-based consulting group alongside the former executives of Starbucks, Jamba Juice, and Pizza Hut. Both the NRA’s current CEO and top lobbyist earned spots on Washingtonian magazine’s 2021 list of “Most Influential People,” the index of Beltway insiders “who’ll be shaping the policy debates of the years to come.”

Leadership that’s so tied to chains comes as no surprise, since most of the organization’s more than $4.3 million in dues revenue comes from its 165 corporate members. Starbucks, Yum! Brands (owner of KFC and Pizza Hut), and Darden paid $50,000, $79,000, and $150,000, respectively, to the NRA in 2019. Members also include food and beverage behemoths like PepsiCo, which regularly pays the NRA between $250,000 and $500,000 in dues, as well as hospitality giants like Disney, which shells out between $50,000 and $100,000 annually. Another top revenue source, according to the association’s spokesperson, is from “the ServSafe suite of training products,” which offers operators and staff food safety and service training.

Some of that money goes toward schmoozy receptions on Capitol Hill, and the NRA’s newish headquarters on L Street—“larger, cooler digs,” Washingtonian reported in 2013—which has a conference room named for Coca-Cola. The NRA has spent more than $5.7 million on federal campaigns since 2007, making it the second-largest food funder after the Farm Credit Council, which lobbies on behalf of the country’s nearly $1 trillion agriculture industry. Roughly 80 percent of the NRA’s campaign spending goes to Republican politicians; when the group boosts Democrats, it’s typically those with a conservative bent, or the chairs of congressional committees key to its interests, such as agriculture. Its top five recipients over the last 15 years have all been Republicans; House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) leads the group with $56,000 in receipts since 2007, according to a report from Feed the Truth, a food industry watchdog group. (Unsurprisingly, the NRA opposed the 2001 McCain–Feingold campaign finance reform bill.)

The crown jewel of that political operation is its lobbying. The NRA spends an average of $3 million a year on lobbyists, a total of more than $38.4 million in the past decade. Its leading lobbyist, Sean Kennedy, served under President Barack Obama as a liaison to moderate Republican and Democratic senators. But on the whole, “it’s a very conservative group,” says Craig Holman, a campaign finance and lobbying expert at Public Citizen, a consumer advocacy organization. “They’re heavily skewed toward the Republicans.”

Where there are efforts to regulate, the NRA appears. When New York City Mayor Mike Bloomberg proposed a ban on extra-large soda servings in 2012, the NRA made sure no such ban took hold at the federal level. The NRA has repeatedly opposed clean energy legislation, citing chefs’ preferences to use gas in the cooking process. Its war on expanding health benefits remains a constant: When President Obama attempted to pass universal health care 15 years after Clinton, the NRA again backed the successful fight against its demise. These efforts have been replicated on the state level through its Restaurant Advocacy Fund, which targets “legislators and special interest groups” whose “numerous bills and regulations” could “hurt restaurants’ ability to remain in business.” And as for paid sick leave for restaurant workers? That remains a nonstarter thanks to their lobbying.

By Washington standards, the NRA’s level of political spending puts it near the middle of the pack, but the group is “more influential than those amounts would suggest,” Public Citizen’s Holman explains. That’s because its powerful corporate members also shell out millions, rowing their boats in the same direction as the trade group.

“That’s just the tip of the iceberg,” Holman adds. “There aren’t a lot of trade associations that carry that kind of weight.” He puts the group’s influence on par with that of PhRMA, the trade organization that represents the pharmaceutical industry (even though the pharmaceutical lobby spends significantly more). The NRA also operates much like the US Chamber of Commerce, a trade group that used to pursue small-business interests until CEO Tom Donahue took over in 1997. Now it spends more on federal lobbying than any other organization, backing GOP candidates and a big business agenda.

And as with the chamber, the NRA kept up its small-business facade, despite its corporate leanings. When the NRA is summoned before Congress, it frequently sends an independent restaurateur—often well-connected and wealthy—to appear on its behalf. At some point in their remarks, owners drop a line like this one from Washington, DC, restaurant owner Geoff Tracy in 2008: “I believe, in many ways, I represent the American Dream,” citing “hard work, education, and an entrepreneurial spirit” as a recipe for success, and reminding lawmakers that restaurants are “rooted in communities and our neighborhoods.”

All of this is, of course, technically true. But the NRA is not broadly representative of independent restaurants’ needs or realities. Instead it engages in a sort of “political identity theft,” argues Sarah Crozier of the Main Street Alliance, a progressive small-business advocacy organization. Tax breaks, deregulation, privatization—that’s not necessarily the agenda of small-business owners, she notes.

“At their core, what they’re saying is that businesses, both large and small, have shared common interests, and the base assumption there is wrong,” Crozier adds. “It’s part of the powerful narrative that the business Right has perpetrated over the past few decades.”

When Briggs first heard in late January 2020 that Covid-19 had been detected in nearby Seattle, he and Bolton stocked up on hand sanitizer and, later, when hoarders depleted supermarkets, 80-proof vodka to see if they could make it themselves. He’d heard mumblings that other restaurants were thinking about shutting down for a few weeks. “Initially, we were like, ‘Shutting down? That’s such a big move. Do we want to find out more information?’” Briggs recalls.

But he didn’t know who to ask. The Reel wasn’t a member of any local restaurant or hospitality associations—and certainly not a member of the National Restaurant Association. (“They just seem like a complete corporate entity that only works for large corporations,” Briggs tells me. “I have no idea what they’re doing besides trying to advocate for, like, Applebee’s. No friend of ours.”) Other restaurant owners were similarly at a loss. On March 16 that year, Democratic Gov. Kate Brown banned gatherings greater than 25 attendees. But neither she nor the state’s health department offered any guidance to restaurants. Portland chefs began to wonder if there was any way to operate safely.

The restaurateurs didn’t know anyone who knew much about the government—except for Erika Polmar, an Oregon food and farm advocate with a cult following for her traveling farm dinners. She wasn’t a public health expert or a lawyer, but she had nearly gone to prison for failing to obtain the permits required for those dinners, a most Portlandia of crimes that turned her into an advocate for land-use changes. When the pandemic forced her to retreat to her couch, “my phone started lighting up with texts and calls from chefs I’ve worked with,” Polmar recalls. Their messages had a similar tenor: Nobody is supporting us, no association is working for us, and we can’t figure out how to get in touch with the governor. “‘You know a thing or two about policy. Can you help us?’” Polmar recalls them saying.

Polmar helped write a letter, signed by more than 60 Oregon restaurant owners and employees, asking Brown to shut down the state’s restaurants and bars but also to give them the financial support to do so. “The very act of serving food to a diner requires that we violate social distancing protocols,” the letter read. “We find ourselves faced with the impossible choice of putting our staff at risk physically or financially.” Brown finally ordered dining rooms to close days later but offered nothing by way of compensation. Briggs and Bolton had decided to close the Reel shortly before.

The dynamic was repeated in cities and states across the country. But as the crisis escalated, only the corporate players had a direct line to the government. On March 17, President Donald Trump and Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin held a call with a dozen top executives of nearly every major US food chain, including Wendy’s, Domino’s, and Subway. Trump encouraged the brands to keep their drive-thru and delivery services going—a pivot most smaller operations couldn’t easily make or preferred not to, since staying open would put the health of their employees at risk.

The same week as Trump’s meeting, Portland chef Naomi Pomeroy told Polmar she was joining a call with some other national chefs to talk about the crisis crippling their industry. She’d seen the letter Polmar had written—would Polmar like to attend? On March 18, Polmar and about two dozen chefs and restaurateurs held the first call of what would become the Independent Restaurant Coalition. Though they hadn’t intended to create an alternative to the NRA, the group soon became just that. The idea for the coalition began with Tom Colicchio, who, in addition to hosting Top Chef, owns seven luxury restaurants across Los Angeles, Las Vegas, and New York. As he closed his businesses and laid off nearly 500 employees, Colicchio received a random call from a lobbyist friend he’d met through his advocacy work on food and farming issues. “I joked, ‘Independent restaurants need a lobbyist,’” Colicchio recalls, “and his response was, ‘That’s a good idea.’”

Save for Polmar, many of the chefs on that first call were Colicchio’s famous colleagues, amounting to a who’s who of the Foodie Industrial Complex, such as José Andrés and Andrew Zimmern. For most, it was the first time they’d considered dipping their toes into politics. Polmar describes the general feeling as, “‘I don’t think anybody’s representing us. How do we get in there?’” In the coming months, Polmar would become the group’s executive director. The ask? A $120 billion rescue fund for the hard-hit independent restaurant industry.

The NRA was also seeking a dedicated restaurant relief fund—albeit one open to all restaurants, including chains. But although the NRA promised independent restaurants it had their back, Colicchio was skeptical. “Why would I be okay putting my fate in someone else’s hands?” he asked. David Chang, who owns the Momofuku restaurant empire, put it this way in a Washington Post interview: “Do you trust Big Tobacco?”

Those fears were well founded. By the time the IRC began holding daily Zoom check-ins, the NRA already had the ear of lawmakers, demanding a carve-out in the Paycheck Protection Program to allow big chains to qualify for the $349 billion fund intended for small businesses. When the program began taking applications in early April, TGI Fridays, P.F. Chang’s, and Ted’s Montana Grill walked away with $10 million loans—each. “They not only got to the head of the line—they got concierge service,” says Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D-Ore.), who represents much of Portland and its surrounding county in Congress. “Sadly, the smaller, independent restaurants—literally mom-and-pop operations—were left to fend for themselves.”

The IRC found its champion in Blumenauer, a 73-year-old lawmaker whose daily uniform of a bow tie, acetate glasses, and a neon-colored bicycle-shaped lapel pin matches his district’s hipster aesthetic. In May 2020, he worked with the IRC to turn its $120 billion relief fund request into a bill with guardrails to ensure it “wasn’t gobbled up by a few large actors as we saw with the Paycheck Protection Program,” Blumenauer says.

As they went from Zoom to Zoom pleading their case to members of Congress used to dealing with NRA power brokers, the chefs-turned-rookie-activists used their novice status to their advantage. “The message that we got loud and clear from some people on Capitol Hill was that they didn’t want to work with [the NRA],” Colicchio says, noting some lawmakers held grudges against the lobby for how the PPP loophole it demanded “burned” small businesses. “We were told by senators, ‘We’ve got to work with you. We actually trust you guys.’”

But the NRA remained a roadblock. It supported a version of the bill, introduced in the Senate, that would allow small-business owners of franchises to qualify. The group praised the Senate’s proposal to support “all restaurants that are suffering.”

“The NRA did not lift a finger in the House,” Blumenauer says, adding that the group “actively worked against us. All along they had a different agenda. They wanted to help the majority of their financial supporters—the big chain operators.”

Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.), then the chair of the Senate’s Small Business Committee, was also steadfastly against any targeted small-business bailouts. Blumenauer says the combination proved devastating. “At any point, if they would have thrown in with us, I’m quite confident that we may have been able to overcome the Rubio objection,” Blumenauer says. Both bills languished for all of 2020, during which time an estimated 110,000 restaurants closed, temporarily or permanently. Not until Joe Biden took office with a Democratic majority in Congress did the Restaurant Revitalization Fund finally pass. It was the NRA’s preferred version of the bill—$28.6 billion in targeted aid to restaurants, including chains and franchises, in the form of grants of up to $10 million to cover any shortfalls between pre-pandemic and 2020 revenues. And it included a two-week “priority filing period” for restaurants owned by women and people of color, many of whose restaurants had been shut out from previous relief. The Reel filed under that special period because Bolton is the majority owner. They learned in May the business would receive a grant of $1.2 million—its entire lost revenue for 2020. “It was a moment of like, ‘Wow, for the first time we can chart a path toward stability,’” Briggs says.

But the victory would be short-lived: Lawsuits filed by white business owners in Texas and Tennessee challenged the legality of such a priority program. One accused the government of “actively and invidiously discriminating against American citizens solely based upon their race and sex.” Three thousand restaurant owners had their funds rescinded—including the Reel. A month after learning they’d received the grant, the Small Business Administration (SBA) informed them that the money would never come. “We went through the floor when we heard that we weren’t getting it,” Briggs says. “That cloud has never fully lifted.”

All $28.6 billion had dried up. The SBA denied the applications of more than 177,000 restaurants—most of them independents like the Reel—due to a lack of funds. Only about a third of all applicants—roughly 100,000 restaurants—received relief. Single-location restaurants had an easier time getting funds than chains did, according to a New York Times investigation, but among the recipients were thousands of Subway, Dunkin’, and McDonald’s franchises, many of which had already benefited from the Paycheck Protection Program. Eleven Hilton and Wyndham-affiliated hotels received a total of $24 million through the fund. There were eight airport and stadium concessions companies that received $10 million each. The IRC cried foul, deeming them “ineligible businesses” given that “Congress clearly spelled out that only eating-and-drinking places should qualify for relief,” it said in a press release. (The text of the bill does cover such businesses, including through loopholes that benefit franchises.) “It was a program with great intentions that was horrifically underfunded,” Briggs says, “and carried out in a way that just became a clusterfuck.”

Replenishing the restaurant relief fund remains the IRC’s top priority. Over the last few months, the group has churned out several letters to congressional leadership on the matter, including one from early December that warned 86 percent of restaurants and bars that didn’t receive grants would close if the fund weren’t replenished. The National Restaurant Association also urged that the fund be replenished, although the group didn’t respond to my questions on how it differed from the IRC in its approach to restaurant relief.

“The amount of relief they got, and the fact that workers got nothing—in every state, even the bluest states—is insane!” Saru Jayaraman shouts to me over the din of traffic on a main drag in downtown Oakland, California, in June. We’re sitting outside Café Gabriela, a Filipino coffee shop, waiting on my coffee and breakfast sandwich—a pair of fried eggs, ham, and a mountain of lemony arugula piled on a baguette. At $12, my total meal was more expensive than a comparable bodega offering, but that’s kind of the point. In most restaurants, the price of food the customer pays does not actually cover the cost to prepare it.

Jayaraman has spent the last two decades fighting to improve working conditions in the restaurant industry. She’s the founder of One Fair Wage, a progressive advocacy organization that has cultivated a network of nearly 2,000 restaurants that have pledged to pay their entire staff at least $15 an hour with tips on top. Café Gabriela, which has been a member for several years, offers what restaurants, to Jayaraman, should: fairly paid work compensated through fairly priced food.

The industry’s reliance on the tipped minimum wage—and the NRA’s efforts to keep it—has made working in a restaurant generally a terrible job, especially for the most vulnerable employees. Workers of color are less often employed in customer-facing roles, and those who are earn far less in tips on average than their white counterparts, thanks to customer bias. Women in particular endure a constant drumbeat of sexual harassment to avoid jeopardizing their tips. Federal law requires restaurant owners to make up the difference between the subminimum wage and the full minimum wage if tips fall short, but a 2014 Department of Labor study found that a whopping 84 percent of owners have violated that rule. Fast-food workers rely on food stamps at twice the rate of those in other industries.

And the pandemic made a lousy job worse. More than one in four restaurant workers lost their jobs in 2020, and nearly half of them failed to receive unemployment insurance, according to an analysis by One Fair Wage. Working for cash tips often means staff don’t report all their income, and their subminimum wage was too low to qualify for any government support. Thanks in no small part to the NRA’s lobbying, many restaurant workers lacked both sick days and health insurance. A study of mortality rates among California workers found that line cooks had the highest risk of death from Covid of any occupation—even health care workers. Bakers and chefs weren’t far behind. And the NRA’s legal arm fought to keep workers on the job as it backed lawsuits against local and state bans on in-person dining, deeming the measures “unfair, unclear restrictions that have no rational basis in fact,” as they did in an Oregon lawsuit.

Meanwhile, not a single penny of the $28.6 billion in restaurant relief funding was earmarked for workers. The restaurants that did get a grant often got a check equivalent to 100 percent of their 2019 revenue, but none was required to be allocated toward staff wages, commonly their biggest expense. The historic suppression of wages, the lack of compensatory funds from the relief package, and a protracted pandemic have converged into an existential crisis.

Yet Jayaraman is feeling hopeful. Once millions of Americans had received vaccines and were ready to go out to eat, the workers to prepare and serve that food were scarce. Headlines touted a “labor shortage” in the restaurant industry, as Republicans and business-friendly Democrats blamed generous unemployment benefits as the root cause. But Jayaraman saw something else. “We don’t call it a labor shortage—we call it a wage shortage,” she says. “The lightbulb for workers, I do believe, is what has resulted in the current staffing crisis. The fact that they won’t go back to work without it—come on. They’re voting with their feet.”

The pendulum of power had started swinging back toward workers. Since the beginning of the pandemic, One Fair Wage has tracked more than 3,000 restaurants that have adopted Jayaraman’s model. Some restaurateurs who had previously fought against ending the tipped wage have begun calling Jayaraman for guidance on how to apply One Fair Wage’s approach—“not always altruistically,” she notes, but “because they just quite often have no choice.” The average paid rate for hourly leisure and hospitality workers climbed above $15 for the first time in 2021, up nearly $2 from the year before. After years of describing a $15 minimum wage as a death knell for the bottom line, Denny’s chief financial officer told shareholders last April that wage increases mandated at the state level had actually improved both sales and guest traffic. The CEO of McDonald’s, which had stopped backing the NRA’s lobbying against the federal minimum wage hike in 2019, told shareholders that the fast-food giant would do “just fine” through any hikes. “It’s a dream come true,” Jayaraman says. “Restaurant owners and workers finally all saying, ‘Things have to change and we’re willing to make those changes.’”

The marketplace has also shifted the policy conversation. Washington, DC, is again attempting a ballot measure to end the subminimum wage. The NRA’s state affiliates recently joined an off-record conversation with fair wage advocates through the James Beard Foundation, eager to learn more about the economics of the model Jayaraman supports. The one group that hasn’t moved is the NRA, which continues to press against tipped-wage reform efforts.

But the IRC also hasn’t thrown its limited weight behind a minimum wage hike. It remains focused on getting the Restaurant Revitalization Fund replenished and isn’t willing to spend political capital on something that could divide its membership. While some restaurateurs in the group favor pushing for higher wages, others don’t. Their founding mission, after all, was to save an industry in crisis, not to reform it. Polmar defends this stance with an analogy to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: “The Restaurant Revitalization Fund is sort of like the base of the pyramid,” she says. “If you can shore yourself up financially, then you have the opportunity to reimagine everything from your menu to your staffing model.”

As the pandemic drags on, there are signs that the National Restaurant Association is losing some of its potency in Washington. The association has changed leadership three times over the last two years, and more fundamental changes may be at hand. “The restaurant industry today is very different than it was in February 2020,” the spokesperson explains. “As the industry recovers and approaches a ‘new normal,’ we’ll work with the industry to determine how to move forward on long-term solutions to issues like paid leave.” Neither Darden nor Marriott listed the NRA on their respective 2020 political disclosures, for the first time in the last five years.

The IRC has recently filed to become its own trade organization, and some independent restaurateurs are casting off their NRA memberships in favor of joining the IRC, according to restaurateurs with whom I spoke. “A lot of people are coming to us because they don’t feel like they’re well represented by the NRA,” Polmar says.

Back in Portland, business at the Reel M Inn is “okay,” Briggs says, grateful for the loyal following that hasn’t balked at the bar’s vaccination requirement. The industry regulars haven’t come in the droves they once did, mostly because many nearby restaurants haven’t returned to full capacity and are still doing a hybrid of dine-in and takeout models that require less staff. “It’s just that domino effect,” Briggs says.

And another crisis looms. At the Reel, a fried chicken order has always come with a free side of ranch dressing. But that was back when mayonnaise was $5.49 a gallon. That gallon is now $18.79, a side effect of the supply-chain disruption. The Reel charges $2 for each takeout container of ranch to offset the cost. “People are so grateful that we’re open and they are grateful to be back out and they are so kind,” Bolton says. “In the same breath, they have a hard time spending that. ‘Oh, now I’ve got to spend two bucks on ranch?’”

In the restaurant industry, customers aren’t just part of a transaction; they’re guests. It’s a meaningful distinction that doesn’t just romanticize an otherwise ordinary fixture of capitalism but places the locus of power almost entirely in their hands. When Bolton arrived at the Reel one Saturday morning, a gray-haired man sat at an outdoor table waiting for her to open. After exchanging pleasantries, he demanded to know whether Bolton was still going to allow him the super-discounted $5 chicken breast special.

“I don’t blame people for not knowing the intricacies of our business. They don’t want to sit there and have me bore them with a [profit-and-loss sheet] about what it takes to do something,” Briggs says. But it’s been a lonely year. “The anxiety and desperation and fear and pain and suffering that has been incurred by us just to simply survive,” he says, trailing off. “If you’re not restaurant industry, people just don’t seem to realize how hard it was.”

But if the industry is to survive, maybe customers should know how hard it is. Maybe they should be prepared to pay more for meals, to be thoughtful about which spots they frequent, to support restaurants that commit to paying staff a fair wage. To let go of an entitlement mentality for the good of the people who fuel the industry, and for the benefit of all the unique eateries that stitch together neighborhoods and communities.

The alternative is what financial analysts predicted of Texas Roadhouse a year ago: The chains will fill the void. “There’s such short-term, small-minded thinking that’s going on in Washington,” Briggs says. “So if they want this whole country to be a Chipotle…you’re going to break every single small business, and you’re only going to work towards the corporatification of everything.”

Correction: A previous version of this story misstated that Carey Bolton and Alex Briggs refiled for SBA funds. In fact, they never refiled. The story has also been updated to correct Erika Polmar’s profession and location.