A prisoner hoeing weeds at the edge of a wheat field in the Louisiana State Penitentiary once asked me: What are you doing here? If he were a free man with a camera, he said, he would be somewhere else—out of the blazing summer sun, far from this 18,000-acre prison on former plantation land.

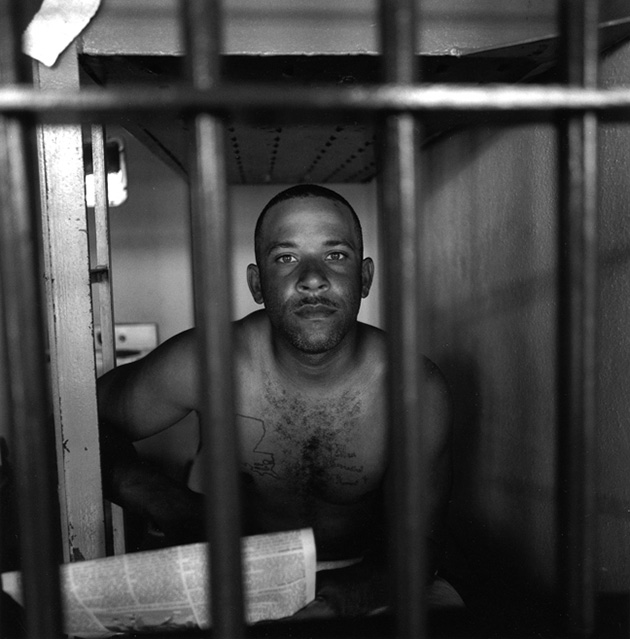

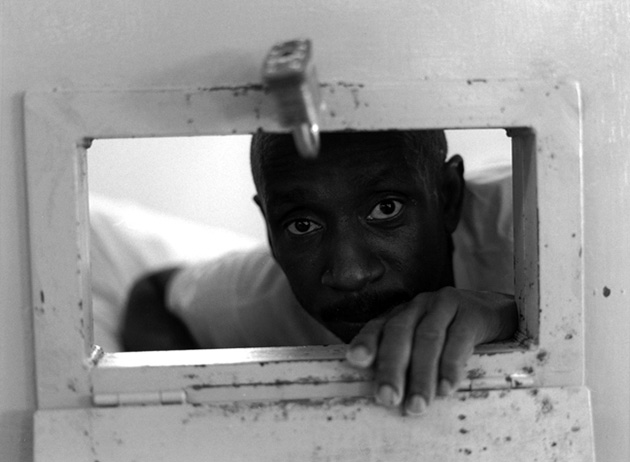

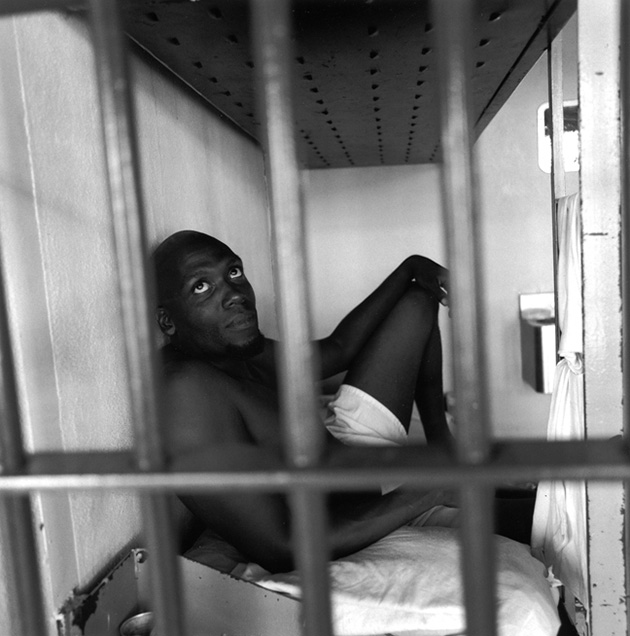

I heard the same question often through the year I spent photographing at Angola. I answered that I’d come to make their largely invisible world visible to the outside. I said I wanted to document daily life in the prison and to represent them as individuals, to reconnect them in a way to a world they had lost. I talked of the prison-industrial complex and the deep-rooted inequalities of the Southern criminal justice system. (Almost 80 percent of the inmates at Angola are African-American and 85 percent of the approximately 5,100 prisoners are serving life sentences.) But as I spoke of injustice, it was obvious I wasn’t telling them anything they didn’t know from their daily lives.

Eventually I stopped trying to explain what I was doing. I simply kept taking pictures. Chaperoned by a prison official at all times, I visited dormitories, cellblocks, and even the prison hospice. I photographed prisoners laboring in the mattress and broom factories, the license plate plant, the laundry, and in fields of turnips, collard greens and wheat. I felt the suffering that ran like a stream through their lives to others—family members, victims—in the outside world. And I hoped that somehow, my images would show them not as part of some desolate hell hidden in a bend of the Mississippi River, but as part of a social fabric, however rent, that includes us all.

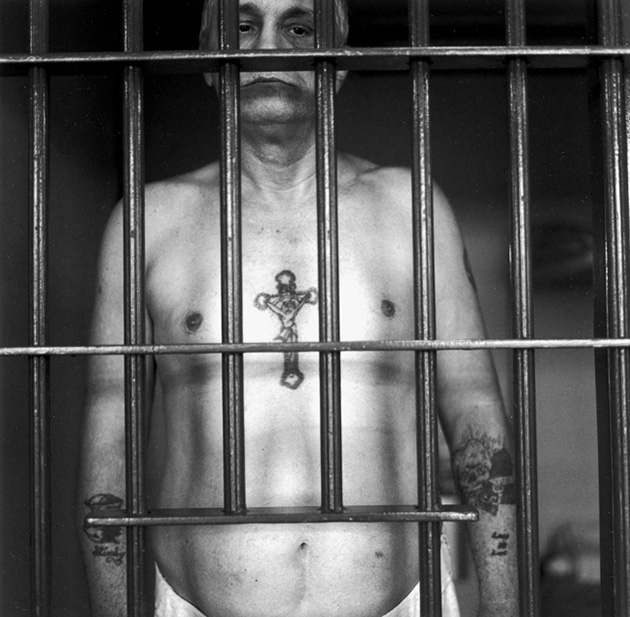

Main prison, cell block A, lower left, cell 8, Louisiana State Penitentiary.

Main prison, cell block A, lower left, cell 15, Louisiana State Penitentiary.

Prison Hospice, Louisiana State Penitentiary.

Cell block A, upper right, Louisiana State Penitentiary.

Cell block A, Louisiana State Penitentiary.

Main prison, cell block A, upper left, cell 4, Louisiana State Penitentiary.

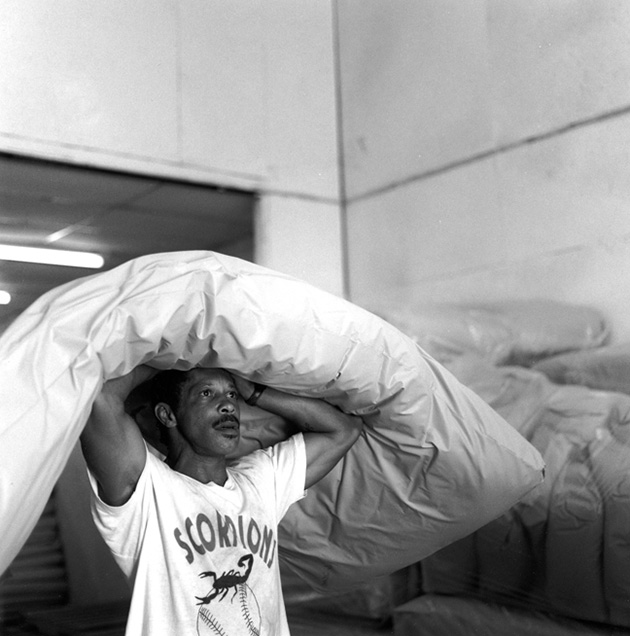

Prison laundry, Louisiana State Penitentiary.

Loads mattresses onto a truck, Louisiana State Penitentiary.

Chopping weeds around wheat fields. He lives in Camp D, Falcon dormitory. Louisiana State Penitentiary.

Louisiana State Penitentiary.

Prisoners in the ring with a bull during Angola’s annual rodeo, Louisiana State Penitentiary.

Death chamber being renovated, Louisiana State Penitentiary.

Prison hospice, Louisiana State Penitentiary.