The hunter climbs high into the mountains in search of his new bird, looking to sharp clefts in the splintered rock faces where golden eagles usually make their roost. He snatches a four-month-old eaglet—old enough to hunt and survive without her mother, but not too old to adjust to a new life among people—and takes her back to his home, where he feeds her yak, sheep, and horse meat by hand. The meal is the start of a lasting bond. For the next decade or more they will be inseparable partners, returning to the mountains to hunt each winter, when their prey—foxes and, at times, wolves—betray themselves with fresh tracks in the ice and snow.

The eagle hunters, known as burkitshi, are members of Mongolia’s Kazakh minority, living in the remote valleys of the Altai Mountains in the country’s far west. Australian photographer Palani Mohan spent five years traveling there, documenting the nomadic lives of the 50 or 60 men who still hunt as their ancestors did 1,000 years ago. They will likely be the last generation of eagle hunters, says Orazkhan Shinshui in the introduction to Mohan’s book, Hunting with Eagles. Shinshui, who is in his mid-90s, is considered the oldest and wisest of the burkitshi.

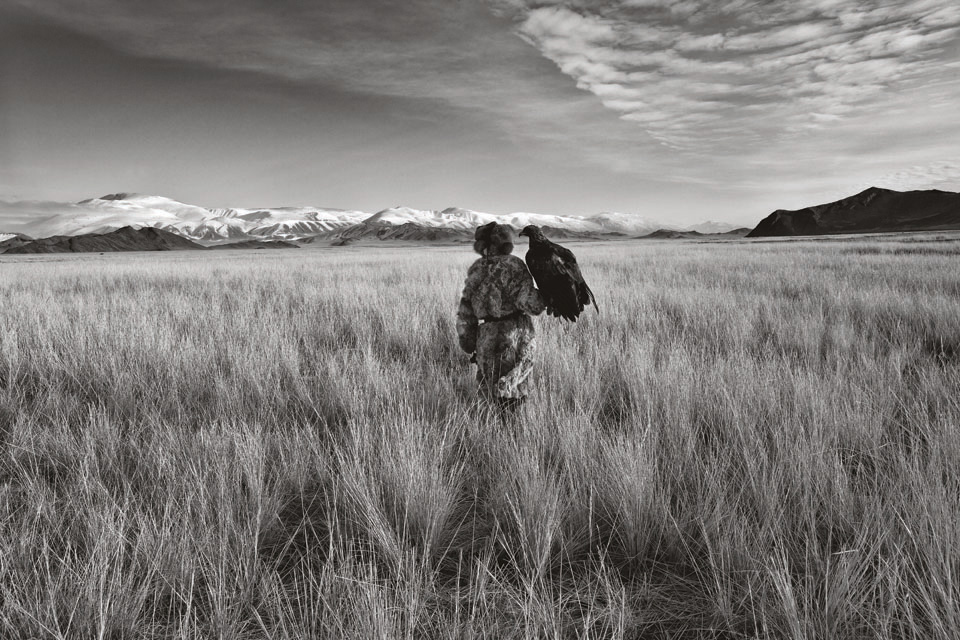

Mohan’s gorgeous photographs capture the howling isolation of the land—flat, treeless valleys dominated by swirling clouds and jutting, windswept peaks. And yet the fierce-eyed eagles seem to preside over the vast emptiness, enveloping the landscape with their enormous wingspan. The hunters, proud and rugged on the hunt, peer out from thick fox-fur coats, bearing the scars of the landscape upon their faces.

But other photographs examine the deep bond between hunter and eagle as it is fostered both on the frigid hunt and in the comparative warmth of the ger, or yurt—the bird calmly cradled in a hunter’s arm, or lying immobilized on the frozen ground, hooded and swaddled against the cold. “When you’ve lived with someone, like I’ve done many, many times with these hunters, you really see the bond,” Mohan says. The hunters gushed with stories of loving their eagles more than their wives, talking about them as though they were children.

Though hunters have partnered with eagles for thousands of years in Central Asia, the young men who would have carried on their fathers’ way of life are choosing a more modern existence. They’re moving east to Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia’s capital, or working along the new roads connecting Russia with China. “They want all the things that any teenager in the world wants. They want money. They want to meet girls. They want to listen to music,” Mohan says. “The old guys like Orazkhan find this very problematic.”

The tradition of keeping eagles in the home has continued, but now it’s mostly for the tourists, Mohan says. “There are golden eagle festivals popping up left, right, and center every year. They’re quite hideous, really; it’s completely traumatizing for the eagles.” He’s heard about eagles that have died of heart attacks, startled by the noise as busloads of iPad-bearing tourists descend upon isolated communities.

Any self-respecting hunter, Mohan says, would never bring his eagle to a festival. “You need to love the bird to be a true eagle hunter, and the bird needs to love you. That does not exist until you live with them out in the sticks.”

Mohan, who was born in Madras, India, and is a vegetarian, says the isolation and brutally cold temperatures, which can plummet to negative 40 degrees Fahrenheit, made the hunting trips the most physically difficult excursions he’s undertaken for his work. The conditions took a toll on his equipment as well—he took to strapping batteries under his armpits and against his thighs to keep them warm and retain their power. “I felt that I was missing the majority of my pictures because I just couldn’t quite work the buttons and I was wearing too many warm clothes,” he says, although he got better at it over the years.

But Orazkhan, who has spent his life here, fears the winters have grown less harsh in recent years, causing many eagles to migrate elsewhere. “He talks about how the winters used to be much longer; the clouds used to be much darker and more fierce,” Mohan says. “The salt lakes that surround him used to stay frozen for many more months than they do now…It really is quite sobering when you’re sitting there in the middle of nowhere, talking to a 94-year-old man who has never heard of the term global warming, and he’s talking about something drastic happening there.”

After 10 to 15 years of partnership, the eagles are taken far from home, given a feast of meat, and left to rejoin the wild—although it can be challenging to keep the bird from circling straight back to its hunter. “Golden eagles are like no other bird,” Orazkhan says in the book. “They want to be with you. They love you. And they love to kill for you. When the time comes to let them go, it’s the hardest thing a man can ever do.”

Hunting with Eagles: In the Realm of the Mongolian Kazakhs is available through Merrell Publishers. In the meantime, enjoy a few more of Mohan’s photos below.

A previous version of this article misidentified the age at which the eagle is taken from its nest.

Here’s more from Mohan at a TEDx talk he gave in Sydney: