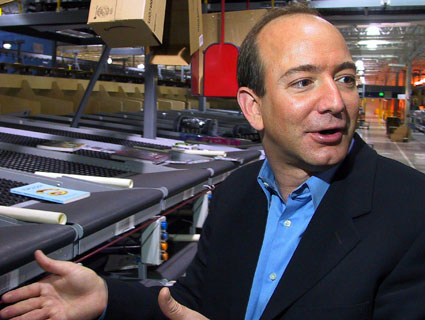

Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos. Mark Richards/Zuma

When can you tax a business? If Amazon had its way, the answer would be never. In June, the online retail giant launched a $5 million petition drive against a new California law requiring online retailers with a physical presence in the state to collect sales tax. At stake: $200 million in revenue, on top of another $100 million for localities.

Amazon refused to enforce the law, arguing that since it’s an online entity, it doesn’t have a physically taxable presence (the company has been waging similar battles in South Carolina, Texas, Illinois, Tennessee, and New York). To drive its point home, Amazon cut off service to its California-located affiliates. If an affiliate could be plausibly be described as having a physical presence in California, Amazon didn’t want anything to do with it, as The New York Times’s David Streitfield explained. Meanwhile, the company barely broke a sweat collecting the 500,000 signatures needed to get a referendum on the measure on the ballot in next June’s election. When you consider the fact that Amazon was asking Californians to pledge their vote to paying less when they buy stuff online, that should be no surprise.

The two sides could be approaching a deal. On Wednesday evening, the two sides reportedly agreed that Amazon won’t have to collect sales taxes until September of next year. In return, it will abandon its referendum, clearing the way for state lawmakers to settle the issue of taxing online retailers for good. But plan could still fall through.

It might seem kind of insane that online businesses could avoid their tax obligations in this way. As Kevin Drum explained, it all dates back to a 1992 Supreme Court ruling that set the physical presence standard excusing online companies from their tax obligations. No one back in the baby-Internet, halcyon days of AOL and Netscape, predicted that online retailers would one day be raking in $150 billion a year. That’s lots of potentially taxable cheddar that states have been leaving on the table.

Currently, there are a host of bills on the federal level aimed at helping corporations use Amazon’s physical presence argument. These bills would hit crippled states where it hurts, at a time they can least afford it. So don’t expect this issue to die after next September. Next to the sheer convenience it offers, avoiding taxing purchases is Amazon’s chief competitive advantage, as Kevin explained:

For all its talk of technology and convenience and selection, Amazon basically stays in business because it can charge slightly lower prices than brick-and-mortar stores. A level playing field might be good for state coffers and the schools and police officers they support, but to Amazon that doesn’t matter. It’s nothing personal, mind you. Just business.

With all that’s at stake—for states and corporations alike—the battle has just begun.

CORRECTION: This post has been edited to reflect that the deal between Amazon and the Californa state house has not been officially agreed to.