Building a Better Ohio's Facebook page (top right and bottom left), <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/progressohio/6217874386/">ProgressOhio</a>/Flickr (top left and bottom right).

Driving west on Interstate 70 away from Columbus, Ohio, the state capital, the landscape quickly settles into flat farmland, a calming tableau punctuated by the occasional billboard pitching fast food or budget hotels or the pious life. (“Meet Nice People: Go to Church.”) The time passes easily, like the endless rows of corn, and before long you’ve arrived in the 8th congressional district, home to the most powerful Republican in Congress, House Speaker John Boehner. On a map, the district looks like a pocketknife bottle opener—flush against the Indiana border to the west, surrounding the city of Dayton on three sides without swallowing it whole.

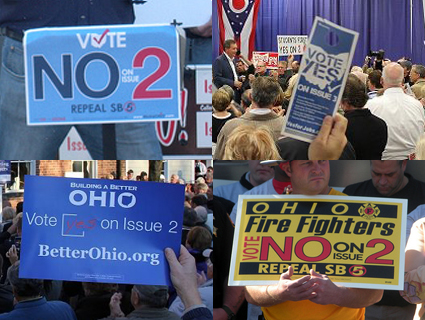

This is solid GOP country. Mostly white, firmly middle class, the 8th’s citizens haven’t elected a Democrat to the House since 1936—Republicans haven’t had a better winning streak in any of Ohio’s 18 other districts. But the current fight over SB 5, Gov. John Kasich’s new anti-union law, is defying political logic. Traveling around Boehner’s backyard and interviewing more than two dozen local pols and average citizens, I’ve encountered a deep divide over Issue 2—a thumbs-up/thumbs-down referendum that will either uphold or SB 5 or kill it.

“People certainly value the public unions and, in particular public-safety unions, but also are not in favor of seeing taxes go much higher,” says Larry Mulligan Jr., the mayor of Middletown, the second largest city in the 8th. He estimates local support for repealing SB 5 at “50-50.”

Mulligan knows firsthand how divisive the idea of curbing collective-bargaining rights—as SB 5 will do for 350,000 public workers—can be. Last December, a member of the Middletown City Council offered a resolution urging the state legislature to overhaul Ohio’s nearly 30-year-old collective-bargaining law. (Kasich, then governor elect, hinted he would do the same.) City leaders were barraged with hundreds of angry e-mails, and about 200 union members packed their chambers to voice opposition.

In the end, the council killed the resolution on a seven-to-one vote. Middletown, smack dab in Boehner’s district, was an opening salvo in the state’s battle over collective bargaining, says Councilman AJ Smith, who organized a protest against the failed resolution and is an outspoken opponent of SB 5.

Smith figures that plenty of local folks, like him, will vote no on Issue 2 on Tuesday, and that what happened with Middletown’s resolution bodes well. “If you could kill a resolution of this kind in the heart of the speaker’s district, you could kill it in the state of Ohio,” he says. Smith also cites the governor’s dismal approval ratings—in late September, Kasich supplanted Florida’s Rick Scott as Americas’ least popular governor—and the failure of pro-SB 5 forces to fully sell the bill to locals.

Driving around the district yields circumstantial evidence for Smith’s theory. In large swaths of Miami, Darke, Preble, and Butler counties, the No on Issue 2 signs appear to vastly outnumber the Yes ones. Many of the No signs mention firefighters or other public-safety workers who will feel the brunt of SB 5 if it takes effect, and many of the people I meet cite concerns over how the law would affect police and firefighters.

“I’m a conservative Republican, fiscally responsible, but I’m gonna vote no anyway,” says a 50-year-old bus driver and former cop with a silver goatee, who agrees to an interview only if I call him by his initials. Clad in a white Ohio State hoodie, JR says he was disgusted by Kasich’s attempt to crush bargaining rights for the men and women he used to work with. “If I didn’t have a dog in the fight, I’d go down the right-wing line,” he says. “This one is personal.”

Todd Morgan, a 42-year-old Huber Heights resident, told me his own union membership will make his no vote an easy one. But he stresses that’d he vote to repeal SB 5 regardless. A few doors down, Chastity Barger, 32, stands in a garage finishing off a cigarette. She cites her dad’s union membership and her friends’ opposition to Issue 2 on Facebook to justify her decision to vote no. Susanne Vulgamore, 61, a retired teacher in Tipp City, doesn’t think partisan politics is a factor. “I have not seen it broken down by party issues,” she says. “It’s that everyone knows a teacher, or knows a spouse who’s a teacher or firefighter.”

People also seem irked about how SB 5 was passed in the first place. Introduced by GOP state Sen. Shannon Jones, whose district overlaps with Boehner’s, it was rammed through the legislature despite sizeable public protests. In the process, it grew to more than 300 pages, an off-putting length to nearly every Ohioan I interview. “I’m just not in agreement with the way the politicians went about pushing the changes on us versus negotiating with unions,” says Joey Johnson, 51.

The 8th District residents who told me they would vote yes on Issue 2 mostly complained about what they saw as scare tactics by Kasich’s opponents—chiefly We Are Ohio, a labor-funded group that has raked in more than $20 million to repeal SB 5. “Most people are caving to the fear that cops and firefighters are going to disappear,” says Kevin Keller, 46, as he crossed the main drag in the town of Piqua. “But that’s so overblown.”

Other supporters claims Kasich’s bill was aimed at helping Main Street. “I think the governor’s trying to save money,” says Eric Baker, 29, who was shopping in the town of Troy. “It’s gonna make cash-strapped towns like this one be able to survive and get by.”

But nearly everyone, regardless of their stance, predicted Issue 2’s defeat—and recent poll numbers suggest that it could well be toast. AJ Smith believes the widespread opposition underscores how little the usual political lines matter in this particular fight. “This is not about Democrats; this is not about Republicans,” he says. “This is about right and wrong.”