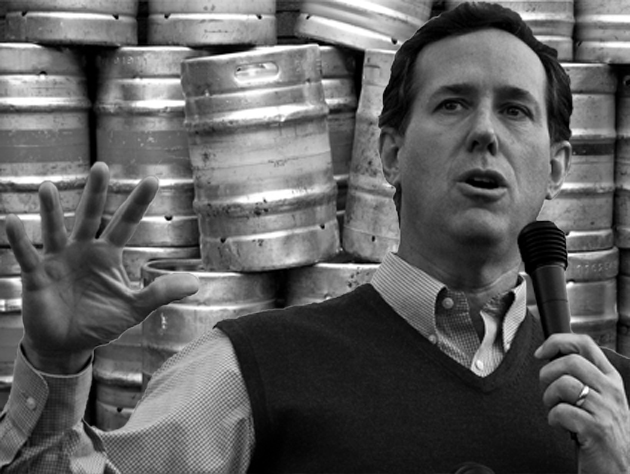

Former Sen. Rick Santorum (R-Penn.)Brian Cahn/ZumaPress.com; <a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/cat.mhtml?lang=en&search_source=search_form&version=llv1&anyorall=all&safesearch=1&searchterm=keg&search_group=&orient=&search_cat=&searchtermx=&photographer_name=&people_gender=&people_age=&people_ethnicity=&people_number=&commercial_ok=&color=&show_color_wheel=1#id=29284762&src=a734d4a838cc44cc70b70b7661d1c798-1-96">Shutterstock.com</a>

Rick Santorum might not be the political candidate you’d most associate with a keg party. But during his 12 years in the Senate, few members did more to promote the suds industry’s interests in Washington than Santorum.

Big Beer is big business in Pennsylvania, home to major breweries like Rolling Rock, Yuengling, and Keystone. And the beer industry has worked hard to make its voice heard in Washington, channeling millions into lobbying and campaign contributions. From 1995 through 2006, Rick Santorum was one of the upper chamber’s biggest beneficiaries of beer industry cash. Wholesalers, brewers, and their top executives filled Santorum’s coffers with at least $80,000 in campaign donations. And they got their money’s worth: Four times during his two Senate terms Santorum pushed to cut the beer excise tax by half, over the protests of economists and public health experts who say that a lower tax would lead to a loss of revenue and lives.

The beer excise tax isn’t the hottest topic on the campaign trail, but it’s serious business in Washington, where the alcohol industry spent $79 million on lobbyists between 2001 and 2006 alone. The industry-backed Beer Institute, to take one example, spent $3.9 million on lobbyists over that period, and chief among its goals was reversing a seemingly innocuous piece of the vast federal tax code. Set at the flat rate of $9 per barrel in 1951, the federal excise tax on beer (paid by the brewer) went unchanged for 40 years, until it was raised to $18 per barrel in 1991.

The beer lobby opposed the new standard long before Santorum came on board, and sought willing allies in Washington. In 1997, the New York Times noted that “the politically powerful beer industry has been hoping to persuade Congress to reduce the excise tax on beer.” To help win support for repealing the excise tax increase, Anheuser-Busch bankrolled a “Roll Back the Beer Tax” web campaign that launched in 2002, touting the Main Street cred of “Joe & Jane Six Pack: The Average American Beer Drinkers” and leaning on the work of the Beer Institute.

But since the tax is not indexed to inflation, the real tax rate has been steadily eroding since the Eisenhower era; the current rate actually marks a 75 percent decline from its original value, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

“The name of the game is to deflect attention at all costs from the fact that really we should be raising beer taxes and the most brilliant way to do that was devised by the beer industry by creating this ‘roll back the beer tax’ campaign,” explains Michele Simon, president of the industry watchdog Eat Drink Politics. Santorum took up the industry’s agenda in Congress. “He was just parroting what the beer industry had told him to say,” Simon says.

In some cases, almost literally. Santorum’s floor speeches and public statements in support of his beer tax repeal measures read like an almost verbatim rehash of industry talking points.

Here’s a statement from the Anheuser-Busch-backed website, RollBackTheBeerTax.org: “In 1990, Congress raised taxes on luxury items like expensive cars, fur coats, jewelry, yachts, and private airplanes and doubled Federal excise taxes on beer. Though most of the luxury taxes were repealed in 1993, the beer tax remains in place.”

Here’s Santorum in a 1998 floor speech introducing his beer tax repeal bill: “The federal excise tax on beer was doubled as part of the 1991 Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act…While taxes on furs, jewelry, and yachts were repealed through subsequent legislation, the federal beer tax remains in place with continued and far reaching negative effects.”

Here’s Jeff Becker, president of the Beer Institute: “The tax on beer is one of the most regressive of all taxes in the federal and state tax codes.”

And here’s Santorum in 1998: “The excise tax on beer is among the most regressive federal taxes”—and again in 2003: “I am proud to once again sponsor a bill to repeal this obsolete and regressive tax on working Americans.”

“He was just parroting what the beer industry had told him to say.”

According to Santorum, the tax increase had cost the American economy 50,000 jobs since 1991—including 30,000 in the beer industry itself—and he estimated that 43 percent of the cost of beer was a result of state and federal taxes. Both of those dubious figures have been trumpeted by the Beer Institute, the industry-funded shop that adds charts and figures to the beverage industry’s talking points.

Santorum, who did not respond to a request for comment from Mother Jones, has defended many of his less palatable legislative pursuits by noting that he was merely sticking up for his constituents. But if today’s comparatively tame tax rate is costing the beer industry tens of thousands of jobs, it’s tough to see how. The Center for Science in the Public Interest touts Bureau of Labor Statistics calculations showing that from 1990 to 2000—roughly the time period Santorum was fretting about the crippling effect of the excise tax—the beer wholesaler industry actually added 8,000 jobs, offsetting the 8,000 jobs lost in the beer manufacturing sector (as with the rest of the American economy, the industry has been shedding manufacturing jobs for decades). And despite Santorum’s claims, the beer excise tax is a lot less regressive than, say, federal tobacco taxes.

But there’s another issue at play here, too. According to public health researchers, when the beer industry saves money, the rest of society ends up picking up the tab.

Lowering the beer excise tax “would lead to an increase of sales of alcohol and an increase in drinking, and that would lead to an associated or proportionate increase in the health problems associated with alcohol,” says Alex Wagenaar, an epidemiologist at the University of Florida who has studied the impact of the tax on public health. “It’s chronic disease for people that drink heavily, it’s also, just for people that occasionally drink more than a very small amount, [an] increased risk for car crashes, pedestrian injuries, fights and assaults and things like that.”

That’s part of the reason why the Centers for Disease Control recommends increasing excise taxes on all alcohol products. So does Mothers Against Drunk Driving (although the group’s focus has been on the state level). In Florida alone, Wagenaar estimates that between 600 to 800 lives could be saved each year if the state’s real tax rate was returned to its 1983 level. A 1999 paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research posited that “raising the price of alcohol by one percent would decrease the rate of [domestic] abuse by 3.1-3.5%.”

Bad policy or not, Santorum wouldn’t be the first Republican nominee with deep ties to Big Keg. John McCain’s wife, Cindy, owned a majority stake in her family-owned beer distributor, which donated tens of thousands of dollars to the National Beer Wholesalers Association’s PAC at a time the organization was locked in a lobbying war with Mothers Against Drunk Driving.

You won’t hear a peep from Santorum about the excise tax these days, though, and he’s made only brief mentions of suds on the campaign trail. He told reporters in Iowa City that he prefers stouts and bocks to IPAs, and last August informed the Des Moines Register‘s editorial board that calling gay marriage “marriage” was like calling water “beer.” (He’s clearly never tried Keystone Lite). Santorum might not be the candidate you’d most like to have a beer with. For 12 years in Washington, though, he was the toast of the industry.