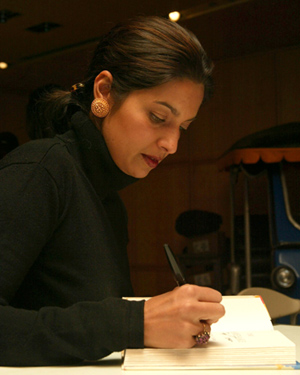

Nancy Kaszerman/ZUMA

In an essay exploring her love of sentences in last Sunday’s New York Times, the great writer Jhumpa Lahiri put together some awful sentences. I say “put together” intentionally: The sentences themselves were mostly fine, at turns even terrific, but in several places they were assembled quite awfully. This surprised me in light of Lahiri’s literary talent and the reputable publication to which she was contributing. Where the heck was her editor?

A few paragraphs into the piece (inaugurating a Times series called, ahem, “Draft”), Lahiri explained how artful sentences are essential to great literature—that they “remain the test, whether or not to read something.” The rest of the paragraph was a demonstration of a writer allowing her impulse for metaphor to spring off the page, wrestle her to the floor, tie her to the desk, and run out to the corner store for a six-pack and a lottery ticket. She continued:

The most compelling narrative, expressed in sentences with which I have no chemical reaction, or an adverse one, leaves me cold. In fiction, plenty do the job of conveying information, rousing suspense, painting characters, enabling them to speak. But only certain sentences breathe and shift about, like live matter in soil. The first sentence of a book is a handshake, perhaps an embrace. Style and personality are irrelevant. They can be formal or casual. They can be tall or short or fat or thin. They can obey the rules or break them. But they need to contain a charge. A live current, which shocks and illuminates.

This seems to taste like chicken, but is dissatisfying because you know it’s not chicken. Chew on it again, this time with a brief annotation of its tangled metaphorical sinews:

The most compelling narrative, expressed in sentences with which I have no chemical reaction, or an adverse one, leaves me cold. [chemistry, temperature] In fiction, plenty do the job of conveying information, rousing suspense, painting characters, enabling them to speak. [visual art, and possibly mechanics or magic] But only certain sentences breathe and shift about, like live matter in soil. [meaning what? tree roots? worms? gophers?] The first sentence of a book is a handshake, perhaps an embrace. [now they are human] Style and personality are irrelevant. They can be formal or casual. They can be tall or short or fat or thin. They can obey the rules or break them. [with human traits and behaviors] But they need to contain a charge. A live current, which shocks and illuminates. [or objects possibly carrying electricity]

I decided to keep reading even though there was additional metaphorical muck to wade through. (“Sentences are the bricks as well as the mortar, the motor as well as the fuel.” A nice harmonic touch there with “mortar” and “motor,” but say what?) I’m an admirer of Lahiri’s work; her first collection of short stories, the exquisite Interpreter of Maladies, was a touchstone for me as a MFA student and resides in my cherished-books section at home. Even here, with her very next paragraph, Lahiri takes your hand and pulls you close, sharing her enthusiasm for reading in a foreign language and what that can teach the true lover of language. It’s the same length as the prior paragraph but uses only one metaphor.

Maybe I’m being a little unfair here—after all, the piece was in a newspaper, not one of the Pulitzer prize-winning author’s books. And Lahiri did include a few lines I found memorable: “The urge to convert experience into a group of words that are in a grammatical relation to one another is the most basic, ongoing impulse of my life.” Now that’s an impulse I can relate to.

If anything, Lahiri’s essay underscores a truth that most of us who spend our days crafting sentences know: Unless you were born the equivalent of Mozart or Michael Jordan, you not only appreciate but also demand having a good editor to back you up. Even if the only one available is, well, you.