The wooden and steel parts I need to build my untraceable AK-47 fit within a slender, 15-by-12-inch cardboard box. I first lay eyes on them one Saturday morning in the garage of an eggshell-white industrial complex near Los Angeles. Foldout tables ring the edges of the room, surrounding two orange shop presses. The walls, dusty and stained, are lined with shelves of tools. I’m with a dozen other guys, some sipping coffee, others making introductions over the buzz of an air compressor. Most of us are strangers, but we share a common bond: We are just eight hours away from having our very own AK-47—one the government will never know about.

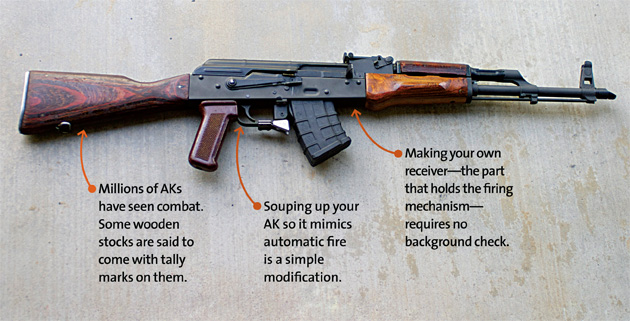

The AK-47, perhaps the world’s best-known gun, is so easy to make and so hard to break that the Soviet-designed original has spawned countless variants, updated and modified versions churned out by factories all over the globe. Although US customs laws ban importing the weapons, parts kits—which include most original components of a Kalashnikov variant—are legal. So is reassembling them, as long as no more than 10 foreign-made components are used and they are mounted on a new receiver, the box-shaped central frame that holds the gun’s key mechanics. There are no fussy irritations like, say, passing a background check to buy a kit. And because we’re assembling the guns for our own “personal use,” whatever that may entail, we’re not required to stamp in serial numbers. These rifles are totally untraceable, and even under California’s stringent assault weapons ban, that’s perfectly within the law.

Among those ready to get going at this “build party” (none of whom wanted their names used) are a father-son duo getting in some bonding time and a well-bellied sixtysomething with a white Fu Manchu who “loves” the click-ack! sound of a round being chambered. Assembling a Romanian variant is a builder wearing a camo jacket and a hat embroidered with an AR-15 rifle above the legend “Come and take it.” His knuckle tattoos read “PRAY HARD.”

We crowd in as our three hosts, all expert gun assemblers, hand out waivers with a list of questions: Are you a convicted felon? Ever been dishonorably discharged from the military? Addicted to drugs? Mentally unstable? The guy in camo looks up and, to much laughter, says, “So it’s all ‘No,’ right?”

The hosts collect our paperwork without checking IDs. We don eye protection and gloves, and soon the garage is abuzz with the whir of grinders, cutters, and drills. Sales of receivers—which house the mechanical parts, making a gun a gun—are tightly regulated, so my kit comes with a pre-drilled flat steel platform. Legally, it’s just an American-made hunk of metal, but one bend in a vise later and, voilà, it’s a receiver, ready for trigger guards to be riveted on. Sparks fly as receiver rails to guide the bolt mechanism are cut, welded into place, and heat-treated. The front and rear trunnions, which will hold the barrel and stock, are attached to the receivers.

Now I need a hand. A stout guy with caramel skin, tired eyes, jet-black hair, and a penchant for peppering his sentences with F-bombs assists me. He starts hammering the barrel into the front trunnion. “If this were an [AR-15] and we did this, we’d be crying doing so much damage,” he says. “But an AK, you can drop this thing in shit, drag it through the mud, smash it against the ground, pick it up, pull the charging handle, and keep shooting. That’s why they’re so popular.”

Durability and simplicity are why AKs have become the most widely distributed guns on the planet since their 1947 debut. They began proliferating in the late ’50s, when the Soviets permitted “fraternal countries” to manufacture Kalashnikovs at will. Soon they spread from one hot spot to another, their reputation for ruggedness and reliability growing along the way. Now there are as many as 70 million in circulation. Colombian drug lord Pedro Guerrero and Saddam Hussein’s son Uday had them plated in gold. Both Hezbollah and Mozambique display them on their flags.

Many kits come from stockpiles in former war zones. “I can guarantee you this one has bodies on it,” says one of the hosts as I peer down the barrel of a Yugo RPK. It’s lined with grit and soot. My host says the AK I’m building is an Egyptian “Maadi” that came to the United States via Croatia, likely having been shipped there during the Yugoslav wars. He tells me some wooden stocks come with tally marks notched in them.

We prep the metal components in a sandblaster and submerge them in a phosphoric acid solution to protect the steel from corrosion. Finally, we grease and assemble them, semi-automatic firing controls included. Owning a gun that can shoot full auto, like these did in a past life, is effectively illegal under federal law. But you can buy a souped-up stock that will harness each shot’s recoil to help trigger the next, a bit of clever engineering that mimics automatic fire—and stays on the right side of the law. Adding one would be a simple future modification.

The first guy to finish is all smiles, but he has a question: “Say some Johnny Law comes up who don’t know shit about this law, and I’ve got an AK without a serial number—then what?”

“There’s a series of laws that make this legal,” says one of the hosts. “Just print those up and have them with you in case Johnny Law does come by.”

The next morning I do exactly that before tossing my AK in the trunk and heading to a gun store so busy I have to take a number. I pick up a barrel cleaner, a 10-round magazine, and 40 bullets before driving out to Jawbone Canyon, federal land northeast of Los Angeles. I park on a bluff, walk to a spot where I can aim at a mountain of scrub brush and sand, and load five rounds. I empty the magazine in seconds. Their reputation has been rightly earned: AKs are popular because they work—every time.

I’m left wondering: Seeing how easy this is, are build parties monitored? Do hand-built weapons ever surface in crimes? Are the cops worried? When I call local law enforcement representatives from Los Angeles, Orange County, Santa Ana, and Garden Grove, they say they’ve never heard of such a thing. “That doesn’t happen here,” says Bruce Borihanh, an LAPD spokesman. But a cursory browse of online gun forums is enough to show that, well, clearly it does. There seems to be one about every month. Plus, I just attended one less than an hour’s drive from his office.

I’m reminded of what one of the build party hosts said before I left: “Remember that thing I told you about why people do this: These builds can happen only because they aren’t blown out to the public and law enforcement.”

People are selling AKs like mine on Armslist.com—the eBay of firearms—for as much as $1,600. In most states, there are no records tracking such private sales. California residents have to go through a certified dealer to sell them legally. But since this AK is untraceable to begin with, who’s to know how I choose to unload it?

Between you, me, and Johnny Law, here’s what happened to my homemade AK. Back in my garage I use a grinding wheel to cut the receiver in half and the other components into pieces. I put the scraps back in the cardboard box the kit came in and leave it for the garbage truck.

Target Demographics

Don’t call it an assault weapon! “Modern sporting rifle” is the term of art preferred by the National Shooting Sports Foundation to describe civilian versions of military rifles such as the AK-47 and M16. So who owns them?

• Around 3% of Americans have a modern semi-automatic rifle such as an AR-15 (the consumer version of the M16).

• 2% of semi-automatic rifle owners have 7.62 x 39 mm rifles, the most common caliber for AK-47s. 76% have .223 rifles, the most common caliber for AR-15s.

• 84% of owners are men. 86% are white. 60% have two or more semi-automatic rifles.

• Top reasons for owning a modern semi-automatic rifle:

Collecting: 28%

Avoiding future weapons bans: 27%

Target shooting: 18%

Protection: 17%

Hunting: 6%

• 25% made their most recent semi-automatic rifle purchase online, 10% at gun shows.

• 59% have a 20-plus-round magazine in their most recently purchased semi-automatic rifle.

• 28% say they’ve spent more than $600 on accessories and customization.

Sources: NSSF/Harris Poll, NSSF (PDF, PDF)