<a href="http://www.zumapress.com/search_results.html?SRCH1=syria+rebel&srchtype=&kwd=&person=&person_text=&timerange=&ksrchtype=&RESULTSPERPAGE=96&FILESrchType=is&FILE=&agency=&newspaper=&keyName=&colName=&agencyName=&newspaperName=">Daniel Leal-Olivas</a>/ZUMA

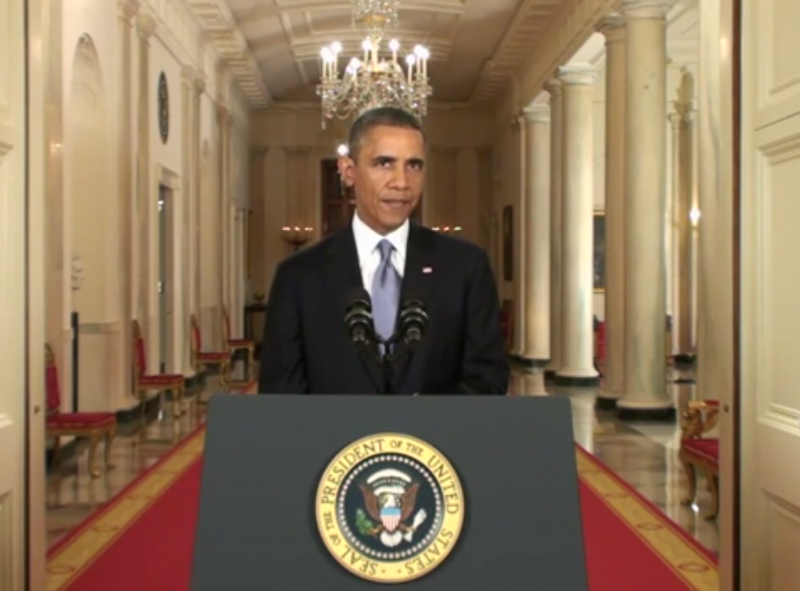

In recent weeks, the Obama administration and hawks favoring a strike on Syria have called for the continued support of supposedly moderate rebels fighting Bashar al-Assad’s regime. The United States has been sending millions of dollars in nonlethal aid to the rebels since February, and in June President Obama authorized secretly supplying weapons to opposition fighters. But with hundreds of Syrian rebel groups battling the regime—ranging from the relatively moderate Free Syrian Army (FSA) to the Al Qaeda-affiliated al-Nusra Front—can the administration ensure that US aid is not winding up in the wrong hands? A system designed to monitor the disbursement of nonlethal supplies to the rebels is supposed to make sure assistance goes only to vetted fighters—but, according to government oversight experts, it relies on too much good faith.

The Syrian Support Group, a US-based nonprofit that is the only organization the Obama administration has authorized to hand out nonlethal US-funded supplies to the rebels, insists it keeps track of who’s receiving this assistance based on handwritten receipts provided by rebel commanders in the field. According to Dan Layman, a spokesman for the group, this level of oversight is sufficient to guarantee US assistance is going to the right rebels and is being used appropriately. “What we’re getting from [FSA commanders] in receipts directly reflects what’s been given out and to whom, I’m very confident,” he says. “The government regularly asks us for updates and new receipts, often faster than we can produce them.” Layman doesn’t know if or how the US government verifies these receipts.

Khalid Saleh, the spokesman for the Syrian National Coalition, the chief political body representing the US-backed rebel forces, says countries supporting the rebels are doing audits of the delivery of lethal and nonlethal supplies, but he adds that he “cannot comment on which countries are performing the audits.” The State Department did not respond to questions from Mother Jones.

In 2012, Brian Sayers, then the Washington lobbyist for the Syrian Support Group, told McClatchy that “obviously, it’s always going to be difficult to say who’s the end user for every cent, every dollar, but we don’t see that the military councils will provide funds to the fringe groups.” Relying on local commanders to guarantee US assistance is managed effectively could lead to “massive corruption,” warns Aki Peritz, a senior policy adviser for Third Way and a former CIA counterterrorism analyst. Peritz notes that the supplies being handed out by the Syrian Support Group can be sold for cash or traded for weapons and ammunition.

Charles Tiefer, a law professor at the University of Baltimore and a former commissioner for the Commission on Wartime Contracting in Iraq and Afghanistan, says that in war zones, “it’s in a commander’s interest to give exaggerated numbers. We often see situations where a commander starts out with, say, three brigades, and then drops to one brigade, and continues to faithfully give receipts for the other two missing units. We call them ‘ghost employees.'” He adds, “I think Syria is the Wild, Wild West as far as knowing who is doing what.”

Here’s how the nonlethal aid system works. On April 30, the Syrian Support Group began receiving State Department contracts, worth about $12 million so far, to deliver supplies—including MREs, combat casualty bags, and surgical equipment—directly to Syria’s Supreme Military Council, the group that runs the Free Syrian Army and commands more than 560 military brigades. The US-based Syrian Support Group transports the supplies to the main Supreme Military Council warehouses*, and from there the the SMC takes over distribution. (The Syrian Support Group has also donated about $300,000 to $500,000 in cash to the rebels, but that money comes from private donors, not the US government.)

Saleh, the spokesman for the Syrian National Coalition, says that “the concern that lethal and nonlethal aid not fall into the wrong hands is shared by our coalition.” He says that every FSA brigade must meet certain conditions, including abiding by the FSA’s constitution, not having children or foreigners in their units, and accepting regular audits by the Supreme Military Council and countries providing aid.

The FSA’s top general, Salim Idriss, and his senior commanders are technically responsible for vetting the hundreds of FSA military brigades receiving US-underwritten supplies, but some of this work falls to province-level military councils and lower-level commanders at field offices around the war-torn country. “A commander from a particular area will authorize a group of soldiers to go to a Supreme Military Council warehouse, and then write a detailed receipt saying this unit picked up three crates of MRE rations from the warehouse,” Layman explains. The receipts are signed by the commander of the unit picking up the supplies and the local warehouse director, who is also under the command of the Supreme Military Council. Layman notes that his organization confers with senior commanders daily and has a staffer in Syria (a former Pentagon employee) who is responsible for oversight.

“The field-level offices talk directly to the Supreme Military Council staff, and the staff figures out exactly how much aid a certain brigade needs from the warehouse based on its size and combat activity,” Layman adds. “We’ll often see receipts that say a group has received only three or four cartons of MREs, so I don’t believe there’s any abuse of access to supplies.”

Tiefer, the former Commission on Wartime Contracting commissioner, says ensuring proper oversight requires more “than just fiddling with a receipt system.” He recommends that the US government establish an oversight body to monitor State Department aid to Syria, or assign this oversight responsibility to an existing inspector general.

Given the makeup of the Syrian opposition forces, there is a good chance that some US assistance could find its way into the wrong hands. There are up to 150,000 rebel fighters in Syria, some of whom are not affiliated with FSA, and at least 16 percent of the rebels are considered “radical,” according to the Syrian Support Group’s own estimate. “When I worked at the [CIA’s] counterterrorism center, for Iraq we estimated that Al Qaeda made up 8 percent of the insurgency,” says Peritz. “This is way worse—this means there are at least 15,000 extremists in Syria.”

US assistance ending up with radical elements of the opposition is not the only problem; this aid could also reach rebels committing atrocities. Last week, the New York Times posted a video of what it reported to be FSA-armed rebels executing shirtless prisoners. The Syrian Support Group issued a statement disputing the Times report, claiming the rebels in the video were from a non-SMC affiliated outfit that did not receive any supplies or funding from the Supreme Military Council.

This spring, one militia leader affiliated with the FSA—his brigade has since been kicked out—was filmed eating a dead soldier’s heart. “This stuff happens rarely, but it’s unfortunate,” Layman says. “With the guy who was eating a heart, he was part of a moderate faction…We work with Idriss and let him know that he needs to prevent these things.”

FSA supporters maintain that it can be hard for Americans to distinguish between radical and moderate rebels—and contend the current vetting process should be trusted. There’s “quite a bit of nuance in these forces,” says Yaser Tabbara, executive director of the Syrian American Council, a group advocating on behalf of the Syrian opposition. “Some of these forces have a religious undertone, they are practicing Muslims, but that does not necessarily make them extremists or against a civil Democratic order.”

Update: This post previously stated that the Syrian Support Group gets supplies to the border. Layman clarifies that the group makes sure it gets to the main SMC warehouses.