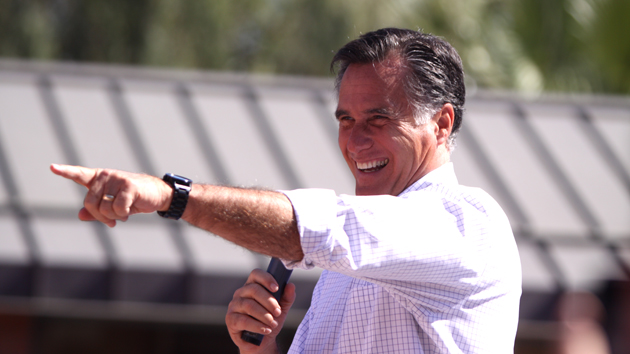

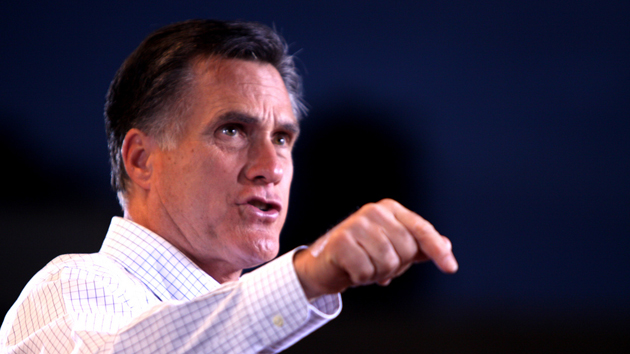

<a href="https://www.flickr.com/photos/gageskidmore/6878658111/">Gage Skidmore</a>/Flickr

The political media world has been in a tizzy these past few days due to the news that Mitt Romney is serious about taking a third stab at a presidential run. On Friday, the Wall Street Journal reported that Romney had told a group of Republican fat-cat funders—who else?—that he was pondering a 2016 bid. On Monday, the Washington Post revealed that Romney was trying to get the band back together, calling former aides and donors and informing them he was almost ready to jump in. With Jeb Bush, another GOP prince with a business career open to political attacks, plotting his own 2016 moves, Romney’s actions raised the possibility of a dynasty-versus-dynasty clash that would cause awkward conversations in country clubs and corporate boardrooms across the land, with the two tussling to win the hearts, minds, and mega-dollars of the GOP establishment. Given that the voting base of the Republican Party will likely be motivated by tea party passions, not centrism or concerns about electability, a Romney-Bush primary battle might be akin to a contest to make the best salad at a cannibals’ convention. Nevertheless, it promises to be a bitter and bare-knuckled brawl, as each camp has already begun shooting spitballs at the other.

For Romney, the key question is this: What would he do differently than last time? In 2012, he did manage to win the GOP nomination, but he achieved that within a profoundly weak Republican field. Rick Perry opposed his way into inconsequence. And Romney only had to vanquish Newt Gingrich, Rick Santorum, Jon Huntsman, Ron Paul, Herman Cain, Tim Pawlenty, and Michele Bachmann—none of them serious contenders. In the general election, he was widely panned—even by Republicans and conservatives—as a less-than-stellar campaigner who could not fully exploit the external factors (a still-sluggish economy, low approval numbers for President Barack Obama) that afforded the Republicans a good chance of seizing the White House. And, of course, there was that 47 percent moment—for which Romney has been offering contradictory and factually-challenged explanations ever since.

This race promises to present Romney with more serious contenders. And in these early days of the Romney-Bush slugfest, there are signs that the problems that plagued Romney four years ago will re-emerge in this new iteration. Jeb Bush reportedly plans to release a decade or more of his personal tax returns. Romney stubbornly refused to do so three years ago—and handed the Obama campaign an easy, what-is-he-hiding issue. Will Romney relent this time around? How would he explain yet another switcheroo? And in recent months, Romney has been privately telling Republican influencers that Jeb Bush, as a presidential candidate, would have a Mitt Romney problem. Well, that’s probably not exactly how Romney has put it, but in making a case against Bush he has pointed out that Bush’s business ties—for instance, he worked for Lehman Brothers before the financial collapse—would leave the brother of George W. Bush open to the sort of anti-plutocrat assaults that descended upon Romney in 2012. Yet if Bush would be vulnerable to such criticism in 2016, couldn’t Romney expect to experience a rerun of what occurred last time? Has he done anything since his concession speech—say, spend his days building homes for low-income Americans—that would inoculate him from a reprise?

There doesn’t yet seem to be much of a New Romney in the making—though the twice-failed presidential candidate has reportedly told donors that should he enter the fray he would aim to run to the right of Bush. (This appears to be more a decision of calculation than principle, which, no doubt, Ted Cruz, Rand Paul, and others will note.) So what might Romney change up for a 2016 bid? Here’s a modest suggestion: no behind-closed-doors fundraisers.

Romney need not be reminded that his 47 percent comments were surreptitiously recorded by bartender Scott Prouty at a May 17, 2012, fundraiser at the lovely Boca Raton, Florida, home of hedge-fund tycoon Marc Leder. The price to get in the door: $50,000 per plate. It was in this ritzy setting—with no media present—that Romney, responding to a question from one of the 1 percenters in attendance, dismissed almost half of all Americans as freeloaders who do not take responsibility for their own lives. It’s a fair assumption that Romney spoke freely in this instance because he felt comfortable in Leder-land. Moreover, the power of the video was enhanced because it showed this candidate speaking within his natural environment—think of it as wildlife footage—and revealed that what goes on in private can be quite different than what voters are permitted to see.

So Romney ought to make a pledge: no more exclusive chats just for the benefit of zillionaires. Whenever he has a fundraiser, he should allow the media to attend. (For small soirees at fancy homes, there can be a pool crew. No need to trample the garden or ruin the rugs.)

In an interview with the New York Times last year, Romney did note that were he ever to campaign again, he would want a constant reminder that anything he says could be recorded and used against him:

I was talking to one of my political advisers, and I said: ‘If I had to do this again, I’d insist that you literally had a camera on me at all times.’ I want to be reminded that this is not off the cuff.

But Romney was clearly more worried about inadvertently uttering something stupid and believed he would need extra help to prevent him from going off script. That’s a start. But the larger point concerns transparency: In Boca, Romney was able to speak differently than he would in public because he was with like-minded swells in the safety of Leder’s mansion.

Promising to end private talks with those who can afford to pay tens of thousands of dollars for the privilege would signal that Romney now realizes that political access due to wealth is undemocratic and that politicians should not be allowed to get away with sharing their real positions in private with patrons while singing a different tune before the voters. Most people don’t remember that at that Boca Raton dinner Romney expressed a much different and more hawkish view on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict than the position he had stated in public. Voters deserve to know what the candidates truly believe—at least as much as the donors.

It’s tough to see how Romney 2016 will explain away his best-known and most notorious words of 2012. In private, he has told GOP millionaires that he is thinking of running as a candidate who will address poverty. (It seems as if he has swiped the issue that Rep. Paul Ryan was developing, now that Ryan, Romney’s ticket-mate in 2012, is not running for president.) Perhaps this is Romney’s strategy for de-47izing himself: Talk about the poor. And there’s nothing wrong with that. Yet he might also help his cause if he takes a step that shows he knows how much he screwed up in Boca and that indicates he wants to run a different kind of campaign. And there’s this: swearing off private fundraisers will have the benefit of ensuring that Romney does not make the same mistake twice.