Mother Jones illustration

In the early 1960s, researchers noticed that women seemed to have lower rates of heart disease than men—but only until menopause, when women’s estrogen levels dropped. At that point, their levels were similar. To get to the bottom of the discrepancy, they set up the first-ever study to test hormone supplements as a preventative treatment for heart disease. In the study, researchers enrolled 8,341 men—and exactly zero women. It would be some 30 years before a comparable clinical study would look at how hormone therapy impacts women, in women.

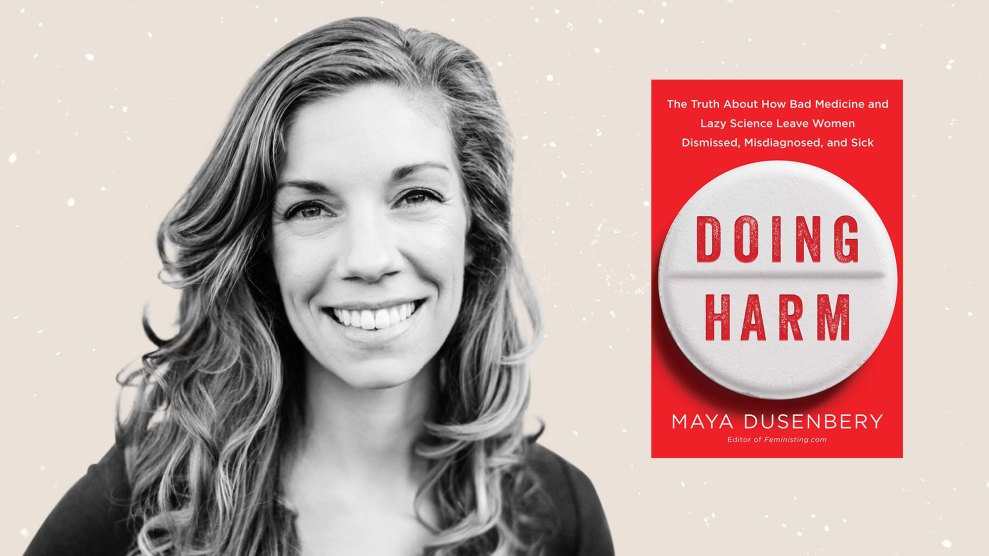

Maya Dusenbery’s new book, Doing Harm: The Truth About How Bad Medicine and Lazy Science Leave Women Dismissed, Misdiagnosed, and Sick, is a seemingly endless catalog of examples like these, which, taken together, lay out the myriad ways in which sexism affects the medical care that women receive. It’s full of horrifying personal stories as well: Consider Maggie, who, as a senior in college, spent 48 hours trying to convince doctors that she was in excruciating pain, barely able to breathe. Her vitals were normal, so a doctor told her, “You need to calm down. I think you’re having a panic attack.” Over two days in and out of the ER, doctors blamed her pain on her being a “stressed-out student,” a “dramatic personality,” and “a drug-seeker looking for prescription painkillers.” By the end of those two days, doctors realized that Maggie was not suffering from anxiety. One of her organs had ruptured, and she was going into septic shock.

The idea that sexism influences the medical care women receive is not new, nor is it that surprising. But Dusenbery’s book goes beyond observation and, through hundreds of studies and an immense amount of empirical research, explains exactly how the problem is systemic. Today, Dusenbery (who previously worked for Mother Jones as a fellow) explains, certain diseases have been studied mostly in men, and “medically unexplained conditions” are often unexplained because they used to be called “hysteria.” Most of all, Dusenbery emphasizes one key, and novel, point: that what she terms the “knowledge gap” and the “trust gap” are mutually reinforcing. “We have been left out of a lot of research,” Dusenbery tells Mother Jones. “That lack of knowledge perpetuates this idea that women are prone to symptoms that have no evident physical cause.”

Mother Jones recently spoke with Dusenbery about the history of sexism in medicine, how the feminist movement might have failed women’s health, and her personal experience with autoimmune disease.

Mother Jones: You begin your book with a personal story about your struggle with rheumatoid arthritis, which is an autoimmune disease. Would you mind speaking about your experience receiving that diagnosis and with the disease? Also, how did it lead you to this book?

Maya Dusenbery: I got diagnosed pretty quickly and easily. I had a textbook case of rheumatoid arthritis, so I was able to diagnose myself pretty easily with Google and get in to see a rheumatologist who confirmed it.

I found out later that I was really lucky in that regard. Once I got diagnosed, as a researcher, I wanted to learn as much as I could about not just rheumatoid arthritis, but also autoimmune diseases. I started learning how common they are, affecting 50 million people in the United States, and 75 percent of those people are women. And then, as I started learning more about other peoples’ experiences getting diagnosed, I realized that a lot of women have stories of feeling like their symptoms were minimized and brushed off as stress or depression, and they experienced really long diagnostic delays.

I was confused about why, if autoimmune diseases are so common, the medical system seemed to be bad at recognizing them and diagnosing them quickly and efficiently.

That got me interested in looking at this topic more broadly. I am a feminist writer and I have written a lot about reproductive health, so it’s not like I was a stranger to thinking about women’s health. But until that personal experience, I hadn’t looked beyond reproductive health to think more broadly about how sexism was playing out in medical care for women when they’re sick, as opposed to [when they need] routine reproductive health care.

MJ: When you started zooming out from reproductive health and thinking more broadly about how the medical system treats women, how did you then decide what to focus on?

MD: That’s a good question. Figuring out how to organize the book was hard. I was hoping to sort of use heart disease as an example of a disease that has been studied largely in men. We had just assumed that we could study men and extrapolate the results to women and not consider the possibility that there may be some sex/gender differences. So the model of the disease that we’ve created—studying men for basically the first 35 years we were looking at it—is a male model. And heart disease is a really clear example of a disease where, once we started doing that research, it turned out, oh yeah, there’s actually a lot of differences [between men and women]. There are differences in symptoms and risk factors. There is a whole kind of female pattern disease that has been not recognized until recently. I was hoping to make the point that that is the case in other diseases too.

Then, I decided to focus on autoimmune diseases because they are so common. Also, I think a lot of the problems women face getting diagnosed for [autoimmune diseases] are applicable to other chronic illnesses. Unlike an acute thing like a heart attack, there are long diagnostic delays for things that are not life-threatening that can go on, and on, and on.

MJ: Reading your book, it was remarkable to realize how little research has been done on some of these subjects. What were some of the books that you see as a precursor for yours?

MD: In some ways I feel like women have been [talking about the trust gap] forever. That has been a complaint since the ’60s and ’70s—it was a major part of feminist critiques of the medical system. Everybody agreed that that was a problem, but maybe it’s been accepted as a problem so much that it’s not seen as a problem. Because it hasn’t become a major part of feminist critiques since.

Osler’s Web, which is the definitive, early history of chronic fatigue syndrome, is helpful in pulling together all of what was happening in the ’80s and ’90s around the disease. But beyond just chronic fatigue syndrome, I found it to be really eye-opening [in showing how] biomedical science is created by humans. We sort of forget that there are actual people making decisions within institutions that then have these enormous and long-lasting effects on what we know in science. And huge effects on people’s lives. We see science as some thing that happens instead of recognizing that human beings do science, and their biases and their mistakes can have huge ramifications.

MJ: As someone who doesn’t have a background in science, that was one of the things that I was very struck by: remembering that doctors are human, scientists are human, and they’re making very human decisions all the time.

MD: Right. And Paula Kamen’s memoir All In My Head also delves a bit into the history of hysteria. She’s one of the only people I came across with some explicit criticism for the feminist movement for not focusing enough on women’s illness. She also offers some insight on why that might be—namely, that second wave feminists fighting to prove that women could compete with men in the workplace and public life were perhaps a bit reluctant to highlight health problems that disproportionately affect women, given that biological difference has always been used to justify women’s inequality.

And I don’t think we’re actually safely past that history today. As we saw in the coverage of Hillary Clinton’s pneumonia during the campaign, women’s sickness still gets used against them in a way that doesn’t happen as much to men. Recall Trump’s comments about Megyn Kelly being on her period, which invoked this long-standing myth that women’s hormones make them unfit leaders.

Certainly, compared to early generations, our generation takes for granted that women can do anything men can do, so there’s perhaps less defensiveness. I think it’s also easier today to talk about sex/gender differences in health because we have a more nuanced, complicated understanding of disease—we know that most diseases result from a combination of genetic vulnerabilities and environmental factors. In other words, we know, in a way that we really didn’t a few decades ago, that biology isn’t destiny—that biology is malleable.

But I do think this has been one of the challenges: the fact that women have been harmed both by medicine treating them as innately different from men—as in the case of women being considered especially prone to psychogenic symptoms or treating their reproductive cycles and transitions as sort of inherently pathological—and from medicine ignoring real sex/gender differences and being blind to women’s unique needs. So we have to walk and chew gum at the same time: being skeptical of medical claims that overstate or essentialize these differences, while calling attention to the ways that differences that in fact really matter to clinical care have been overlooked by taking a one-size-fits-all approach.

MJ: There are so many unbelievable stories about individual women’s experiences with sexism in this book. How did you start finding these women and gathering these stories?

MD: I created a Google Doc calling for stories and posted it on Feministing. I also spread it through my personal networks. From that I got almost 200 people.

The stories that ended up in the book are not even the worst ones. There are lots of stories that I couldn’t include. I hope that people really recognize that these aren’t super rare stories. A lot of the women felt like their stories must be the exception. But when you see in the aggregate how common this actually is, you realize that’s not the case.

There’s a lot of silence around these experiences that I didn’t fully appreciate. I think that there’s a real tendency to internalize what a medical expert is telling you and to assume that if you’ve had an experience like this, it was because you just weren’t advocating for yourself as well as you could have, or maybe it was just your individual bad luck. There’s a lot of power in women starting to talk with each other about these stories and realizing that it’s not just them. It’s not an individual problem, it’s reflective of larger systemic problems.

MJ: Throughout the book, depending on the study or the data that you’re talking about, you’ll mention how things break down for women along racial lines. What did you find about how these experiences differ for women of color?

MD: In most cases, that intersection of race just makes it even worse for women of color. In particular, the stereotype that patients of color are drug seekers was a really prevalent one. In addition to that, there’s an empathy gap that is in some ways separate from the trust gap that affects all women.

Most of those who have looked at gender disparities in treatment have concluded that the problem seems to be most pronounced in women’s initial encounters with health care providers—in that time before doctors have figured out the cause of the pain or fatigue or other symptom and are relying on the patient’s report of their symptoms. That’s when the stereotype that women are overly anxious or emotional or exaggerating or prone to hysteria can lead to this distrust in the reliability of their reports. But once there’s objective evidence that something is really wrong, usually the gender gap closes—or at least narrows. It’s not so much about not caring about women’s symptoms but about just not believing they’re as bad as they say.

But I think medical racism is rooted in a somewhat different problem, or a few different ones, and is more likely to persist past those initial encounters. Patients of color, especially black patients, are under-treated even for post-surgical pain, when obviously there is no uncertainty about there being a real reason for the pain. Experts in racial disparities suggest that there is a real empathy gap at play—an inability to feel moved by, or perhaps even recognize, the suffering of patients of color. And as one of the studies I discussed in the book suggested, for black patients, that may be in part rooted in these really, really old myths about black people having some sort of superhuman invulnerability to pain. Experts also say that patients of color sometimes get under-treated for things like cancer due to an assumption that they either can’t afford or aren’t willing to comply with a more aggressive treatment approach.

I was interested in exploring the actual treatment and medical knowledge that women receive once they’re in the medical system. [I couldn’t] go into the barriers to just accessing [medical care], which obviously, you can write whole books about that as well. It’s important to recognize that in some ways those barriers to access become more important than these issues, because if you can’t go to the doctor, that’s the biggest problem that you face. If you don’t have health insurance that lets you go to two, three, seven, ten specialists to get the proper diagnosis, then you’re just out of luck.

MJ: After laying out how sexism affects the medical treatment that women receive, you write a bit in your conclusion about what we can do. Could you speak a little more about that?

MD: One of the surprising things that I learned was just how hard it is to change medical school curricula and how slow that process is in the best of times, let alone when you’re calling for changes across every clinical area. But there’s a growing recognition that medical education needs to change to incorporate emerging knowledge of sex/gender differences. I think that’s a hopeful sign.

In the last decade or so, there’s also been more recognition that diagnostic errors are this blind spot. We haven’t been tracking them, but we should be. The fact that doctors don’t get feedback on their diagnostic errors means that [errors] become self-perpetuating. And it’s not about individual arrogance, it’s about that lack of feedback. There’s a lot of potential to get better systems in place if that feedback is happening.

And of course, there’s a lot more discussion within medicine about implicit bias around race and class and weight. I hope that the book can spark more attention on the work that is already happening, and also help draw connections between these different areas.

MJ: How can we reach people who may not have access to this information or who may not have the opportunity to read this book?

MD: The problem is that, probably, only the most privileged women are the people who are going to be reading this book. The solution can’t be an individual one where women are just called upon to be better self-advocates. Because one, that just shouldn’t be a burden on anybody. And two, many women don’t have access to the information, language skills, cultural/social authority, and financial resources it takes to become the super-empowered patient who can self-diagnose and go to a million specialists.

That creates this system where there’s a real divide between the haves and have-nots. I’ve been very hesitant, in doing these interviews, to give individual advice because I do think that these are systemic problems and they won’t be solved for all women unless the system itself is radically changed.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Image credit: Caitlin Nightingale

Disclosure: Maya Dusenbery worked for Mother Jones as a fellow.