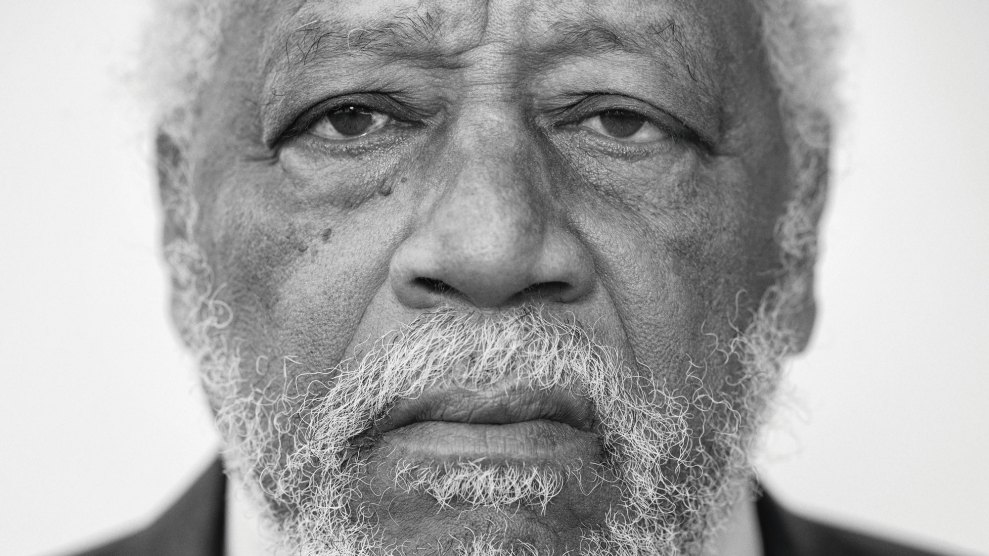

Brandi Levy was suspended from Mahanoy Area High School's junior varsity cheerleading team for sending two Snapchat messages to her roughly 250 followers.Mateusz Slodkowski/SOPA/AP

Update, June 23, 2021: In an 8–1 ruling, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Brandi Levy, the former Pennsylvania student who had been kicked off the high school cheerleading team and charged with violating school policy after sending vulgar Snapchat messages outside of school. Levy and her parents had argued that the suspension was in violation of her First Amendment rights. For more on the case, read below.

Brandi Levy just wanted to blow off some steam. When the rising sophomore learned that she’d been placed on Mahanoy Area High School’s junior varsity cheerleading team for a second season, she took to Snapchat to vent. “Fuck school fuck softball fuck cheer fuck everything,” Levy wrote in a selfie caption with friends, their middle fingers raised. After hearing that a freshman had made the varsity cheer team, Levy sent another Snap: “Love how me and [another student] get told we need a year of jv before we make varsity but that doesn’t matter to anyone else? 🙃” Her messages sparked B.L. v. Mahanoy Area School District—the most important student free speech case to come before the Supreme Court in a half-century.

Levy sent the two Snapchats on a weekend in October 2017 while hanging out at an eastern Pennsylvania convenience store. They went out to her roughly 250 followers, including fellow cheerleaders—one of whom took a screenshot and shared it with the school’s cheerleading coaches. Levy was kicked off the team, charged with violating a school policy against sharing “negative information regarding cheerleading, cheerleaders, or coaches…on the internet.”

When Levy and her parents appealed the decision, the Mahanoy Area School District sided with its coaches. Levy and her family sued the district, arguing that the suspension violated her First Amendment rights. Levy, represented by the American Civil Liberties Union of Pennsylvania, won in district court; the school district appealed, and in June 2020, a federal appeals court again sided with Levy, ordering that she be allowed to rejoin the cheer squad and ruling that “public schools have an interest in teaching civility…but they may not leverage the coercive power with which they have been entrusted to do so.”

The school district appealed again—retaining Lisa Blatt, chair of Beltway law titan Williams & Connolly’s Supreme Court practice, to make its case to the highest court. (Also in Blatt’s portfolio: a notable op-ed in favor of Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s 2018 nomination to the court.) The Department of Justice took the school district’s side, filing a brief that favored a more expansive interpretation of “school speech.”

In May, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in the case, grilling attorneys for both parties on whether, and to what extent, public educational institutions can discipline students for off-campus and online speech—and what impact a ruling may have on schools’ powers to curb harassment. If schools could only discipline “disruptive” forms of speech, attorneys from the Solicitor General’s office argued, addressing discrimination and bullying would become a “nightmare.”

The justices posed scenarios in which harmful or offensive speech might affect a student’s education. If, outside of school, a student told a female student, “You’re so ugly, why are you even alive,” Justice Sonia Sotomayor wondered, would that require school disciplinary action? If male students created a website to rank female students’ appearance and sex lives, Justice Elena Kagan asked, should the school get involved—and how?

The court’s ruling, expected later in June, may have ramifications far beyond Levy’s cheer squad. In May of this year, the ACLU of Indiana filed suit on behalf of a 14-year-old student, I.B., who had been suspended for posting a TikTok video that shared information about classmates who had used racial slurs, including the n-word. Though I.B. posted the video on her own device, off campus, during her summer break—and experienced bullying as a result—her central Indiana public school suspended her, calling the video “slander.”

Gavin Rose, a senior staff attorney with the Indiana ACLU, expects the Mahanoy ruling to affect I.B.’s case: If the Supreme Court sides with Levy, I.B.’s off-campus speech would likely be protected as well. If not, schools may only have to show that off-campus speech could “disrupt” students’ learning—leaving students like I.B. on the hook for exposing on-campus racism.

Levy’s attorney, ACLU national legal director David Cole, told National Public Radio that a ruling broadening schools’ power to punish students for off-campus speech would “transform a limited exception into a 24/7 rule”—forcing students to “effectively carry the schoolhouse on their backs in terms of speech rights wherever they go.” To win her case, Levy will need the court’s 6–3 conservative majority to agree.