Sara Mendez-Morales had lost almost all hope. It was a cold stretch in early February, and she had spent nearly six months in the custody of US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in Butler County Jail, a notorious detention center about 35 miles north of Cincinnati. Former detainees have dubbed the facility the “dungeon” and called their incarceration “traumatizing.” The weeks of being deprived of fresh air or sunlight and unable to step out of the two-person cell for longer than an hour and a half had sometimes led Mendez-Morales to wonder if she should just sign her own deportation order.

Finally, her luck started to change—or so she thought.

Last November, Mendez-Morales had applied for asylum and two other forms of deportation relief with the help of an attorney who argued she was part of a larger group of at-risk “Indigenous Guatemalan women who have reported their abusive ex-partner to the police.” An expert witness familiar with the conditions in Guatemala supported this claim, testifying that he didn’t believe that Mendez-Morales would be “completely safe” anywhere in the country. Mendez-Morales herself was deeply fearful of what awaited her. So over the course of two video hearings before a Cleveland immigration judge, Mendez-Morales, a soft-spoken 34-year-old with a round face and full dark hair, shared her story.

She told Judge Bruce D. Imbacuan how she had left Guatemala in 2007 at the age of 20 after surviving abuse and sexual violence—only to arrive in the United States and experience a different form of it. She had been in America for a few years, she explained, when she met a Guatemalan man named Gaspar. She already had one daughter from a previous relationship and they had another together. Initially, Gaspar seemed kinder and less prone to violence than other men in her life, including an aggressive former partner and an abusive and ruthless father who had often made her feel worthless. But the relationship with Gaspar turned violent and in the spring of 2019, she learned he had abused her then 10-year-old daughter. Undocumented and afraid, Mendez-Morales, who’s also a cancer survivor, reported him to her doctor, who contacted child protective services. Soon she found herself trapped in a nightmare: The police arrived, Gaspar had fled, and she ended up being convicted of child endangerment for allegedly having been complicit in the sexual abuse. Despite maintaining her innocence, she was separated from both daughters and served 500 days in prison. Gaspar, meanwhile, returned to Guatemala.

When she was released from prison in August 2020, Mendez-Morales became a target for deportation. ICE immediately picked her up, and she lost her freedom once again. After she described her ordeal to Judge Imbacuan, he granted her protection from deportation on February 1, 2021. In a 14-page decision, the judge, who doesn’t often side with immigrants, agreed with her lawyer and the expert witness, saying that if Mendez-Morales were deported and her aggressors found her, she’d likely suffer “even worse torture.” His ruling was nothing short of a lifeline for Mendez-Morales. Finally, someone had believed her.

But there’s a catch: The criminal conviction for a serious crime barred her from qualifying for asylum and an alternative form of relief known as withholding of removal, which is available, for example, for people who have been previously deported and are ineligible for asylum. So the judge granted Mendez-Morales what’s known as deferral of removal under the Convention Against Torture (CAT), a temporary safeguard from deportation that has one of the highest legal standards to meet.

For 20 days, Mendez-Morales sat in detention eagerly awaiting her release and reconnecting after nearly two long years with her two US citizen daughters, who’d been placed in foster care. Then ICE appealed the decision. The agency’s lawyer argued that she’d given inconsistent testimony and that the judge had wrongfully found that the Guatemalan government would be “willfully blind” and fail to protect Mendez-Morales. She was consigned to indefinite detention while the appeal was pending.

“I didn’t do anything and yet I’ve paid for it,” Mendez-Morales told me during one of the first conversations we’d have over many months. Speaking from a payphone at the ICE detention facility in Hamilton, Ohio, she continued, crying, “I don’t know why I’m going through this nightmare.”

Sara Mendez-Morales

Courtesy of Sara Liebler

Proving fear of persecution or the likelihood of torture back home to win asylum and other protections such as CAT in a US immigration court is never easy. It’s even more challenging for the thousands of people pursuing cases from detention centers across the country, almost half of whom lack access to legal counsel.

But even for the lucky few like Mendez-Morales who find a lawyer and manage to beat the odds, a win does not mean a smooth path to a life in the United States. ICE holds the power to appeal any decision with which it disagrees (in both detained and non-detained cases), and it often does—which, for those in detention, can mean extra months or years of being locked up after having made a successful claim. “In my own experience and that of colleagues,” says Kim Alabasi, a Cleveland-based immigration attorney working on Mendez-Morales’ case, “the government will almost always appeal cases where a respondent is lucky enough to win.”

To be clear, ICE isn’t obligated to pursue any appeal. Attorneys and officers are instructed to follow a set of priorities and use their prosecutorial discretion. Under the Trump administration, virtually all undocumented immigrants were considered a priority, and lawyers representing the government were encouraged to keep filing appeals, particularly in cases involving immigrants in detention, with criminal convictions, or who were deemed a “national security or public safety risk.” The scope of targets for enforcement under President Joe Biden is more limited, focusing on national security and public safety threat categories as well as recent arrivals at the border. And ICE attorneys are urged to consider a number of additional mitigating or humanitarian factors—serious health conditions, for instance, or ties to the community. And in light of the massive immigration courts backlog of more than 1.3 million cases, a memo from May by ICE’s principal legal adviser states that attorneys can decline to appeal a case if they’re unlikely to win. But the guidance still allows enormous latitude for prosecutors to pursue cases outside of the main priorities and ultimately leaves the decision to release someone at the discretion of individual local ICE field offices.

ICE is under no obligation to keep immigrants in custody. In fact, under a 2004 policy, ICE is supposed to release noncitizens who have been granted asylum, withholding of removal, or CAT while an appeal is pending. Still, ICE enjoys enormous discretion, so exceptions may apply to people the agency considers a national security threat or a danger to the community. Much as with the appeals guidance, ICE officials enjoy a wide latitude to behave as they see fit.

Data obtained by a public records request with the Department of Justice’s Executive Office for Immigration Review, which presides over immigration courts, shows that ICE was responsible for more than half of the 4,252 immigration cases—of asylum, withholding of removal, or CAT—that were brought to the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) between October 2015 and June 2021, fighting to overturn a grant of deportation relief in about 2,700 individual cases. Of those, almost 1,000 involved immigrants in detention who’d been previously awarded protection. The appeals process can drag on for months or years, and the outcome is unpredictable; the BIA can dismiss or sustain or send the case back to the immigration judge for further consideration. In that event, the case might wind its way to federal courts. Even if the immigrant prevails, the prolonged litigation almost inevitably imposes additional emotional and financial burdens. Win or not, it can be a losing game.

Raha Jorjani is an immigration defense attorney with the Alameda County Public Defender’s Office in California and an expert in the intersection of criminal and immigration law. The fact that the government’s decision to appeal keeps noncitizens in detention—even after they have won their case—“is one of the most disturbing aspects of immigration law,” she says. “It causes people with strong claims to give up their cases to avoid suffering the painful consequences of prolonged detention.”

Jorjani has practiced detention and deportation defense for more than 15 years, but one case still haunts her. As a teenager, Walter Cruz-Zavala fled El Salvador and settled in San Francisco, where MS-13 gang members recruited him. After a few months, an informant with the US government convinced him to get a tattoo, one of the generally understood signs of gang affiliation. Cruz-Zavala was then prosecuted for conspiracy as part of a gang crackdown operation; he was placed in federal custody and spent nearly three years in solitary confinement—which amounts to torture under international law—before being acquitted in 2011. But he began drinking as a way to cope with his unaddressed trauma, which then led to a DUI and a conviction for carrying a concealed firearm. Those charges landed him in ICE custody in July 2017.

Cruz-Zavala won his case twice before two immigration judges, based on the likelihood that he’d be tortured in his home country. Still, ICE continued to appeal, and he remained detained in the Mesa Verde ICE Processing Center in Bakersfield, California, for more than three and a half years as his case bounced between the BIA and immigration judges.

In July 2020, the BIA ordered a do-over when his case had already been decided by the second immigration judge, even though it did not cite factual errors or dispute previous decisions, according to reporting by the Intercept. But this time, the judge reversed his decision and Cruz-Zavala found himself back at square one, having to fight all over again, while detained. “You can’t tell your loved ones when or if you’re coming home,” Jorjani says. “The psychological impact of indefinite immigration detention is something I believe we’ve not begun to grapple with as a society.”

That summer, Cruz-Zavala got infected with COVID-19 and recovered. Jorjani filed a habeas corpus petition with a federal district court challenging his prolonged detention, but it was denied months later. Shortly thereafter, Cruz-Zavala finally surrendered to circumstances and gave up on his claims.

The whole ordeal was unlike anything Jorjani had ever seen. “You should win because your arguments are stronger,” she says of the government, “not because you bullied people.”

John Bruning, an immigration attorney with the nonprofit Advocates for Human Rights’ Refugee & Immigrant Program in Minneapolis, puts it simply: “The default is: Even if you win, you stay locked up.” Consider ICE’s detained population in Minnesota, where about 10 percent of the approximately 100 immigrants remain in custody despite having won their cases. One of Bruning’s clients, who had a criminal conviction for drug possession a decade earlier, was detained for 46 months, the longest for an ICE detainee in the state. He had won relief twice and had a third appeal pending with the BIA when he was released in April on a $100,000 bond. Another client, who would call Bruning from detention with suicidal thoughts, had to wait 14 months before being released.

“As time goes on, they start to question their own sanity,” says Bruning. “People are barely holding it together and start acting out because they have nothing to lose and feel trapped. It’s torture for them. They feel like they’re being punished for having won.”

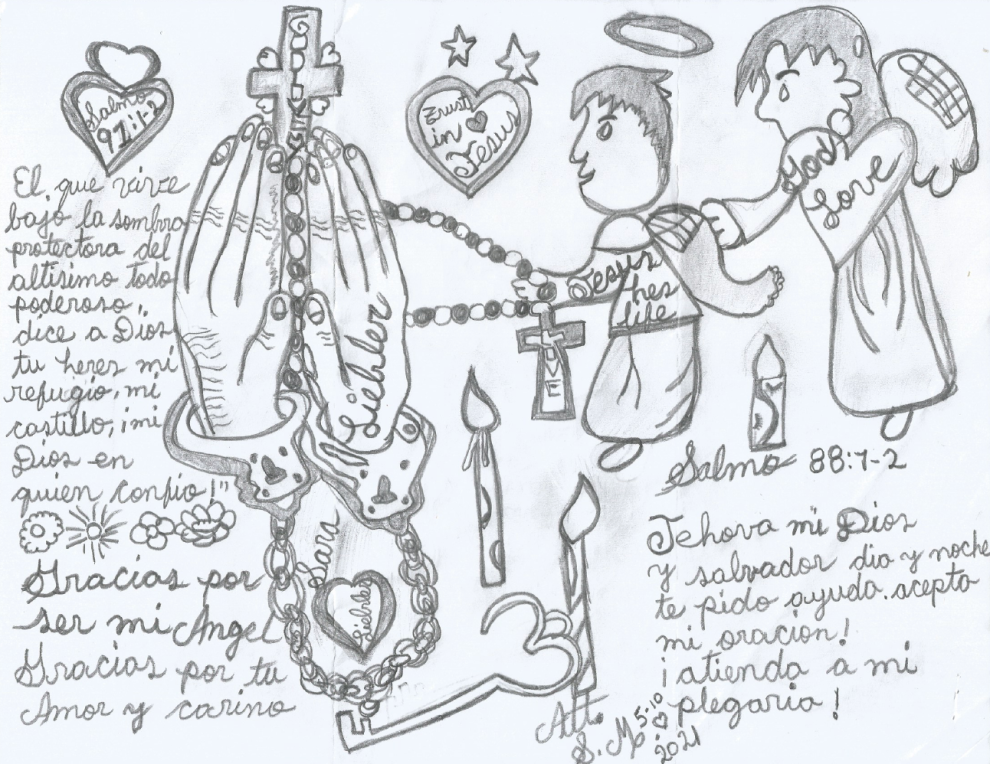

“Thank you for being my angel. Thank you for your love and kindness,” Mendez-Morales wrote to a friend and volunteer.

Courtesy of Sara Liebler

The way Mendez-Morales sees it, she’s paying for the mistakes she made as well as those she didn’t. “I am only a woman who got everything wrong in my life,” Mendez-Morales wrote in a written statement to her lawyer Kim Alabasi, from April 2020. “Since my childhood, I felt like garbage, a child, a young and filthy woman. I always felt my life was not worth anything.”

She was born in San Rafael Pétzal, the second oldest of six children. Mendez-Morales dreamed of being a teacher but had to drop out of school at just 6 years old to help support her family, starting work in the fields growing beans and corn. At home, her father would beat her, sometimes with coffee tree branches, other times with pieces of wood. By the time she turned 8, Mendez-Morales was working six days a week washing the nixtamal to make tortillas and cooking for hundreds of people on a ranch. Whatever money she earned, her father kept.

The sexual assaults began when she was around 13 years old. One rainy afternoon, she had just left a cleaning shift when three men grabbed and drugged her and raped her. She went to the hospital and to the police, but her assailants were never arrested. Mendez-Morales later began working at a restaurant where the owner’s son routinely abused her. When she was only 14, she became pregnant. Her father was enraged, beat her up, and kicked her out of the house. She decided to put the baby up for adoption and learned later that her daughter had been adopted by a family in the United States.

Finally, in 2007, Mendez-Morales decided to flee and follow some family members to find a new life in the United States. She estimates she tried to cross the US border with Mexico seven times, eventually arriving in Arizona and settling in Chattanooga, Tennessee, with relatives. There she became involved in a relationship that turned abusive; her partner threatened to kill her and burned her face with hot water, according to a police report. He was charged with aggravated assault and domestic violence and was deported to Guatemala. She fears that if she returned there, he might find her and seek retribution.

In 2009, Mendez-Morales gave birth to a daughter as a single mother. A few years later, they moved to Ohio and Mendez-Morales started working at a clothing store making $12 an hour and managed to buy a trailer. In 2015, she met Gaspar, who was also from Guatemala and was also undocumented. And once more, despite a promising beginning, she found herself in a relationship with an abusive man.

Their daughter was born the following year. During that time, Mendez-Morales was diagnosed with ovarian cancer and had to undergo surgery and a regimen of radiation therapy. She no longer wanted to have sex with Gaspar because it had become painful, and they grew apart. But any thoughts she might have entertained about leaving him were quashed by her family, who pressured her to stay and “put up with it because all men were like that.”

Then, one Saturday, Mendez-Morales was cooking pepián, a traditional Guatemalan spicy meat stew, before her shift at a laundromat. Her older daughter, then 10 years old, started crying, begging her mother to skip work. She kept asking for her father, which struck Mendez-Morales as odd since he had never been in the child’s life.

Her daughter broke down and told her mother Gaspar had taken her clothes off and had touched her. Mendez-Morales remembers she screamed and reached for the phone to call the police, but Gaspar grabbed it from her hands and broke it. In a court statement, Mendez-Morales described what happened next. Gaspar locked her and the girls in a bedroom for a few days and threatened to flee with their daughter if she reported him.

Mendez-Morales acquiesced but started searching for an apartment. In order to protect the girls, she had to quit her job. Finding an apartment without a steady income or legal documents proved impossible. Mendez-Morales was stuck. She says that she hadn’t been romantically involved with Gaspar for a year, but he forced her to have sex with him while the girls were sleeping. Not knowing what else to do and fearing for her and her daughters’ safety, she decided that at her next radiology appointment she would confide in her doctor. She hoped the physician would call the police, and they would arrest Gaspar.

On April 10, 2019, Gaspar drove her to her radiotherapy session and waited in the parking lot with the younger daughter, who was then 2 years old. As she’d planned, when Mendez-Morales’ doctor entered the consulting room, she confided in him about the abuse. The radiation oncologist listened quietly and told Mendez-Morales to get her baby out of the car while he called for help. But the appointment had already run late, so when Mendez-Morales appeared in the parking lot, Gaspar sensed something was wrong. “Are you staying or are you going?” he asked as he pulled her into the 2018 Mazda pickup and drove away. She kept hoping the police would arrive and follow them. “No one came to help me,” she said. Instead, Gaspar dropped them off at home and fled.

Later that day, an investigator with the Hamilton County Job and Family Services told the local police department he’d been warned of “an adult male having sexual contact and raping a 10-year-old female multiple times over the past five years.” Shortly afterward, a police officer appeared at the older daughter’s school.

Mendez-Morales was at home, worried as the clock ticked past 3:45 p.m. that her daughter still hadn’t come back from school. That’s when the family services investigator and several police officers arrived. A Spanish-speaking interpreter wasn’t immediately available, but nevertheless, they asked her questions about Gaspar and her knowledge of the reported ongoing abuse. Before the day was over, social workers removed her daughters from their home.

In the following days, Mendez-Morales had a supervised visit with the girls. During the visit, Gaspar called her. She says the video call didn’t last longer than a minute and she begged him to come back and turn himself in, even if she feared he might try to kill her. “I was too desperate,” Mendez-Morales told me.

On April 22, less than two weeks after the doctor’s appointment, the police arrested Mendez-Morales. She was charged with third-degree felonies of child endangerment and obstruction of justice. (It isn’t uncommon for women survivors of domestic violence to lose custody of their children to an abusive partner and, in some states, to be criminally charged based on “failure to protect” laws.)

The call was used as evidence that Mendez-Morales was aware of Gaspar’s whereabouts and was trying to protect him. Investigators also relied on testimony from the traumatized 10-year-old to accuse Mendez-Morales of having known about the abuse for a year—which she has disputed in court—and failing to report to law enforcement. Louis Valencia, Mendez-Morales’ criminal attorney at the time, says there were translation issues during the initial investigation when a detective acted as an interpreter. Her daughter’s account of events “jumped back and forth” and wasn’t chronological. Based on the flawed evidence, Valencia told me, he thought Mendez-Morales would have a good chance if the case were to go to trial.

Meanwhile, Gaspar is still wanted by police for multiple counts of rape, and he remains a fugitive. In an email, a lieutenant said the investigation case file and a body camera’s video footage of Mendez-Morales’ questioning couldn’t be released because they’re part of an ongoing prosecution of the male offender.

But as she considered spending possibly 16 years in prison, Mendez-Morales pleaded guilty to child endangerment, and the other charge was dismissed. (She says her lawyer advised her to enter into the plea agreement.) In September 2019, a Hamilton County court judge sentenced her to 18 months in prison.

“They needed to put it on somebody and the only person they had was Sara,” Valencia says. “She did the best she could.”

Sara Mendez-Morales during a video call from ICE detention in August 2021

Isabela Dias

Mendez-Morales spent much of her sentence in the Ohio Reformatory for Women, a state prison outside of Columbus. To cope with the sadness, she washed dishes, exercised, and joined a Bible studies program. “I felt like my life had no meaning,” she says. “For a year and a half, I didn’t want to stare at my face in the mirror; I was disgusted with myself.”

When her sentence came to an end in early August, Mendez-Morales was released—and that’s when she was immediately transferred by ICE to Butler County Jail in Hamilton, Ohio.

The facility was fraught with problems. In an August 2020 report, DHS’s Office of Detention Oversight found 34 deficiencies in the facility’s compliance with requirement in areas such as medical care, telephone access, admission and release policies, and environmental health and safety. Former detainees have described the food as inedible and complained about the lack of a proper recreational area. A civil rights lawsuit filed in December noted a “pattern of excessive use of force, punitive conditions and violence against detainees”; two men, one from Cameroon and one from Somalia, claimed correctional officers repeatedly threatened and beat them, and one detainee was pushed down a flight of stairs.

“They treat us worse than animals,” says Carolina Moreno, a 34-year-old asylum seeker from Michoacán, Mexico, who was detained in Butler County Jail around the same time as Mendez-Morales. “A cat or a dog would be better off than an immigrant in detention.” She fled Mexico in 2015 after members of the Knights Templar cartel kidnapped her mother and death threats and extortion followed. Moreno won asylum about halfway through her 15-month detention, but ICE appealed the case. For the extra months, Moreno longed to be with her 7-year-old son who had come with her to the United States. During this time, she was infected with the h pylori bacteria, a carcinogen that can cause gastritis and ulcer disease, and was ill for weeks, overcome with fatigue and nausea.

In March, Moreno was finally released. But she’s still dealing with depression and panic. “I have evidence that I deserve asylum but still they kept me there as if I were a criminal,” she says. “I feel like they play with our rights.”

Danya Contractor, a coordinator with the local advocacy group Ohio Immigrant Visitation, says she has seen multiple women at Butler County Jail who have won deportation relief and could have been released to the community but stayed detained while ICE filed appeals. In Mendez-Morales’ case, she adds, the government is “punishing a woman we know did all she could possibly do under the hardest circumstances possible.”

On March 17, Alabasi, Mendez-Morales’ immigration attorney, requested Mendez-Morales’ release under ICE’s new detention review process, arguing that she didn’t fit any of the enforcement priorities. After her case was reviewed, a supervisory detention and deportation officer with the Detroit Field Office in charge of Ohio disagreed. The officer determined that Mendez-Morales could not be released because of her criminal conviction for an offense that “is particularly serious as it involves complicity in the sexual abuse of a minor.”

Alabasi responded that Mendez-Morales had in fact reported the abuse, has no history of violent behavior in the 14 years she has lived in the United States, and wasn’t a flight risk. Mendez-Morales also had a pending application for a trafficking visa known as a T visa with US Citizenship and Immigration Services. (Mendez-Morales says that upon their arrival in the United States in 2007, her uncle forced her into prostitution to pay $3,500 to the coyotes who arranged the trip.) But ICE continued to deny Mendez-Morales’ request for release. A spokesperson said the agency keeps following enforcement priorities and makes decisions about custody on a case-by-case basis. “She and I are at our wit’s end at this point in terms of what else can we possibly do to get her released from ICE custody,” Alabasi told me.

In the spring, the Butler County Sheriff’s Department terminated its 17-year-contract with ICE to detain immigrants, and Mendez-Morales was transferred to the Geauga County Safety Center, also in Ohio. Mendez-Morales said at least the food there was better and she could have fresh fruits and vegetables. She was able to see a psychologist and learn more English. But she was also going more than two years without the check-in appointments for her cancer treatment. All along what sustained her was a network of support from community members and organizations who mobilized as part of a campaign called “Suelta a Sarita”—Release Sarita, her nickname—to cover attorney costs and devise a legal strategy to retroactively reduce her criminal sentence and get her out of detention. An online petition asking for her release has garnered more than 13,000 signatures. “This is someone who got swallowed up by the system,” says Pastor Eber Flores of Liberty Heights Church, whom Mendez-Morales called at least once a week. “She’s running a race without a finish line.”

The whole time Mendez-Morales stayed in detention, she hasn’t had visits or calls with her daughters, who have been in foster care for almost two years and are being considered for permanent placement with adoptive families. Earlier this year, her older daughter wrote Mendez-Morales a letter saying she missed her; the younger was just beginning to say her first words when they were separated.

“This indefinite detention, aside from the ways it causes psychological and physical torture, it’s causing irreparable damage to her right to be a mother to her own children whom she gave up everything to protect,” says Sara Liebler, an advocate with Ohio Immigrant Visitation.

But at the same time, in a surprising twist of fate, her ordeal has brought her closer to her eldest daughter, the one she put up for adoption 18 years ago. Mendez-Morales first connected with Maya Rose Bliffeld through Facebook in 2014. Maya, who was 12 years old at the time, and her adopted parents found Mendez-Morales’ family in Guatemala and learned her biological mother had been living in the United States.

“Sara was always part of our story from the very beginning,” Maya’s father, Sebastian Bliffeld, says. Growing up, all Maya had of Mendez-Morales was a picture from the adoption record file. But years later, through occasional phone calls, they began to make up for lost time. Mendez-Morales told Maya she had thought of her every single day and how relieved she was to know she was safe and well. Maya shared videos of herself playing piano and helping her little sister do homework.

“She’s never been dealt a good hand in life. It was sort of a losing battle before she even started,” says Maya, who is now an international studies student at Fordham University. “I just don’t know that she knows how not to suffer.” But she also describes her birth mother as selfless and savvy. Sebastian says Maya is a powerhouse and he recognizes some of the same traits in her biological mother. “She doesn’t just sit back and let things happen,” he says. “She fights and she fights and she fights.”

Maya is grateful to Mendez-Morales for giving her a chance at a better life. She wanted to reciprocate by becoming involved in advocating her release. “A lot of people see a poor woman in a poor situation, but I see a strong woman in an unjust situation,” she says. “Knowing that’s who my birth mother is, someone who has it in her to keep going every day, is incredible and that will stay with me for the rest of my life.”

Finally, on August 26, Maya and others’ efforts and Mendez-Morales’ resilience paid off—she was released from ICE detention. The BIA decided to dismiss the government’s appeal. “The BIA decision was pretty short, just stated that they wouldn’t disrupt the credibility finding and that Sara met her burden,” Alabasi wrote me in an email. She had won her case for a second time.

For Mendez-Morales, the experience was disorienting, long overdue, and a surprise all at once. After Liebler’s sister picked her up from detention, they stopped at a gas station so Mendez-Morales could get a Pepsi. They bought three pairs of trousers and three shirts so she could change from the prison clothes. Her first meal was a steak assado, rice, tortilla, and salad at a Mexican restaurant. “I couldn’t eat everything. My stomach got full,” she told me. “It’s a big change.” In the following days, she went to the church to thank God and had a Zoom meeting with all the people who’d been there for her, including Maya, Sebastian, Liebler, and Alabasi. “I wasn’t alone,” she says. “I did it with their help.”

But the road ahead won’t be easy. Mendez-Morales has already applied for a work permit but she still lacks identification as her passport got lost when she went to jail. “Everything she needs to rebuild her life is on hold now,” Liebler says. Sebastian agrees. “Her life now is completely different from her life before,” he says. “On some level, freedom is not freedom. Yes, she has a roof over her head but she’s still a victim of circumstance.”

As grateful as she is, Mendez-Morales knows she has to rebuild her life. She’s hoping for some visitation with her daughters and perhaps a future as a family. Without them, she feels alone and empty.

“I’m starting all over,” she says. “I’m never going to give up.”

Top image credit: Mother Jones illustration; Sara Mendez-Morales courtesy of Sara Liebler; Smith Collection/Gado/Getty Images