Graeme Jennings/Getty

On Tuesday, the Senate approved four new US ambassadors, something that typically would not pass for breaking news in Washington, DC. But before this week, only 2 of Joe Biden’s 69 ambassador picks had been confirmed, making his diplomatic corps substantially smaller than his predecessors’ at this point in their first term.

Few ambassador nominations are controversial, and the Senate can usually vote them through easily. But this year, Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas) has held up the nominees over a disagreement with Biden’s handling of a Russian gas pipeline in Europe. Instead of permitting senators to vote quickly, which requires unanimous approval, Cruz has made it so each pick requires hours of debate, stopping the Senate from doing other business.

“I’ve made clear to every State Department official, to every State Department nominee, that I will place holds on these nominees unless and until the Biden administration follows the law and stops this pipeline,” he said in August on the Senate floor.

The four nominees to pass Cruz’s blockade on Tuesday were all either former senators (Jeff Flake, Tom Udall) or spouses of former senators (Victoria Reggie Kennedy, Cindy McCain). Cruz, whose office did not return Mother Jones’ request for comment, told Washington Post reporter Seung Min Kim he permitted them to go through out of senatorial courtesy.

Even with those ambassadors in place, the United States still only has four chief diplomats in foreign capitals—the other two picks are stationed at the United Nations. Such a small lineup of ambassadors is not only a historical anomaly—George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump all had at least 20 Senate-confirmed ambassadors by this point in their presidencies—but a serious obstacle to the Biden administration’s ability to conduct diplomacy.

“It’s impossible to imagine a scenario where we can see not having enough four-star generals in place,” said Jenna Ben-Yehuda, president and chief executive of the Truman Center for National Policy. “It would be on the news every day, but that’s exactly what the State Department is facing.”

Biden kept some of Trump’s ambassadors in place, but still over half of all current ambassador postings are vacant, some for a long time: The United States has not had an ambassador to Singapore, for example, since Obama was president, though Biden finally named a nominee in August.

In most cases, the second-in-command or some other senior diplomat can be elevated to fulfill the typical duties of the ambassador, but this kind of promotion has a downstream effect on other officials who are forced to take on more work. It also is not practical in some embassies. “There are many countries who will not meet with anyone other than the appointed and confirmed representative of the president,” Ben-Yehuda said. “The big virtue that the ambassador has is the imprimatur of the support of the White House.”

Biden did not cause this unprecedented delay, but his administration has also not particularly prioritized filling out its diplomatic and national security teams. Despite increasing the size of the National Security Council staff, Biden has not shown the same preference for stocking other agencies.

At the State Department and USAID, “this administration has been pretty much the slowest in modern times in terms of nominating people,” Eric Rubin, president of the American Foreign Service Association and former US ambassador to Bulgaria, told me.

The problem is broader than just the State Department, as the confirmation process has kept many mid-tier positions vacant across the national security agencies. “Only 26 percent of President Biden’s choices for critical Senate-confirmed national security posts have been filled,” the New York Times reported last month, citing research by the Partnership for Public Service, which tracks presidential appointments. Twenty years ago, “57 percent of key national security positions were occupied.”

Cruz is a major reason for that, as are Sens. Josh Hawley (R-Mo.) and Rick Scott (R-Fla.), who have delayed nominees at agencies like the Department of Homeland Security. Hawley also threatened last month to delay all of Biden’s nominees to the State Department and Pentagon unless Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin resign.

The other area of concern for diplomats and scholars who study the Foreign Service is that of Biden’s nearly 70 ambassadorial nominees, more than 60 percent are not career diplomats. When selecting ambassadors, most presidents arrive at a mix between career officials, usually for more difficult posts like in Afghanistan or Russia, and party bigwigs or donors, who tend to get placed in more glamorous spots. As I reported during the Trump era:

Most ambassadors are career foreign service officers, highly trained professionals who have worked their way up through the diplomatic ranks. But a significant minority are so-called “political ambassadors” who come from outside the diplomatic corps—generally a mishmash of campaign donors, ex-lawmakers, and retired military officers.

Ryan Scoville, a professor at Marquette University Law School, researched ambassador appointments over time and found that under Obama, political ambassadors comprised 30 percent of total picks. Under Trump, that figure had climbed above 40 percent. This arrangement—rewarding donors and party leaders with plum diplomatic posts—was actually the source of some outrage from progressives like Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), who vowed during her presidential campaign to “end the corrupt practice of selling cushy diplomatic posts to wealthy donors.”

Biden’s preference for non-career appointees is “well above the historical average,” Scoville said, and like prior presidents, “Biden has proposed to send many of these people to developed countries that are attractive destinations for global tourism. In this respect, the Biden administration has not improved on the practice of the Trump administration.”

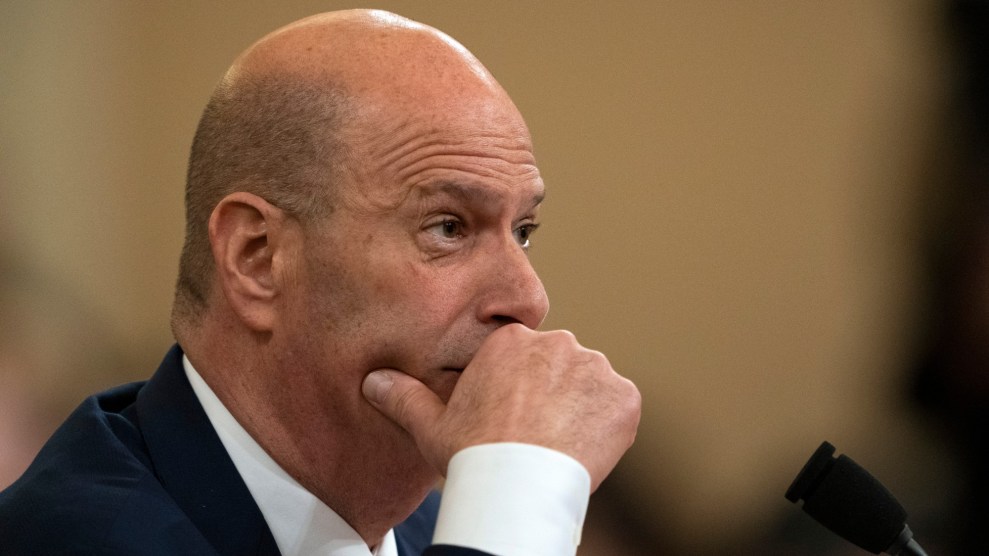

Though Biden has continued that trend, his political ambassadors have tended to be more qualified than some of Trump’s more egregious selections, including hotelier Gordon Sondland of Ukraine scandal fame and a handbag designer who became ambassador to South Africa. Biden’s nominees for ambassador to Poland and Panama are not career diplomats, but they each served as ambassadors under Obama.

Whether they will serve as ambassadors under Biden is a question that, as of right now, only Ted Cruz can answer.