Mother Jones; Getty

Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology, often ranked as the country’s top public high school, lies across the Potomac River from Washington in Alexandria, Virginia. For years, the magnet school’s student body has been majority Asian American, with paltry numbers of Black and Latino students. While the situation at TJ irked the county school board for a decade, and in 2012 drew a civil rights complaint to the US Department of Education, tweaks to the admissions process failed to increase those underrepresented demographics.

In June of 2020, as the murder of George Floyd sparked both nationwide protests and a fresh reckoning with racial injustice, the school released its most recent admissions data. The number of admitted Black students was somewhere under 11—a figure “too small for reporting” due to privacy concerns. A week later, TJ’s principal emailed students and parents: “Our school is a rich tapestry of heritages,” she wrote, but one that does “not reflect the racial composition” of Fairfax County Public Schools. “Our 32 black students and 47 Hispanic students fill three classrooms. If our demographics actually represented FCPS, we would enroll 180 black and 460 Hispanic students, filling nearly 22 classrooms,” she added.

The school board and superintendent began to contemplate a new admissions policy that would increase the school’s diversity, an effort that was pushed along when the state of Virginia soon urged magnet schools to submit such plans.

A backlash quickly formed, as a group of parents called the Coalition for TJ alleged that the school board was purposefully trying to lower the number of Asian American students in an act of anti-Asian discrimination. The group enlisted the Pacific Legal Foundation, a nonprofit libertarian law firm that had recently filed two cases on behalf of Asian American parents in other states who wanted to preserve existing admissions policies at selective public schools.

This month, the Coalition for TJ and PLF’s lawyers will petition the Supreme Court to hear their case. If the justices decide to take it up, they will do so in the wake of a long-sought conservative victory from June, when the court effectively ended affirmative action in college and university admissions. To many on the right, the decision striking down Harvard and the University of North Carolina’s policies was just one battle in a larger war against efforts to increase racial diversity across society—one that could, through the TJ case, again reach the Supreme Court within a year.

This next phase targets admissions policies in K-12 schools, and is an effort to maintain the status quo, even as American public education grows increasingly segregated. Radically, the lawyers driving this test case have invited the Supreme Court to go beyond its rejection of affirmative action and ban admissions policies that do not actually take race into account.

“If the government is simply choosing a race neutral policy in order to achieve a racial result, we are going to object,” explains Joshua Thompson, who leads the Pacific Legal Foundation’s education litigation. “You cannot have a racial purpose consistent with the equal protection clause,” Thompson argues, except “to remedy past government discrimination.”

If the court accepts that argument, it would constitute a sea change—not just in education, but in broader American life. For decades, public officials have considered racial disparities and segregation in arenas as varied as education, pollution, and health policy to be problems government should tackle. Under PLF’s theory, even the desire to eliminate racial gaps could be successfully challenged in court.

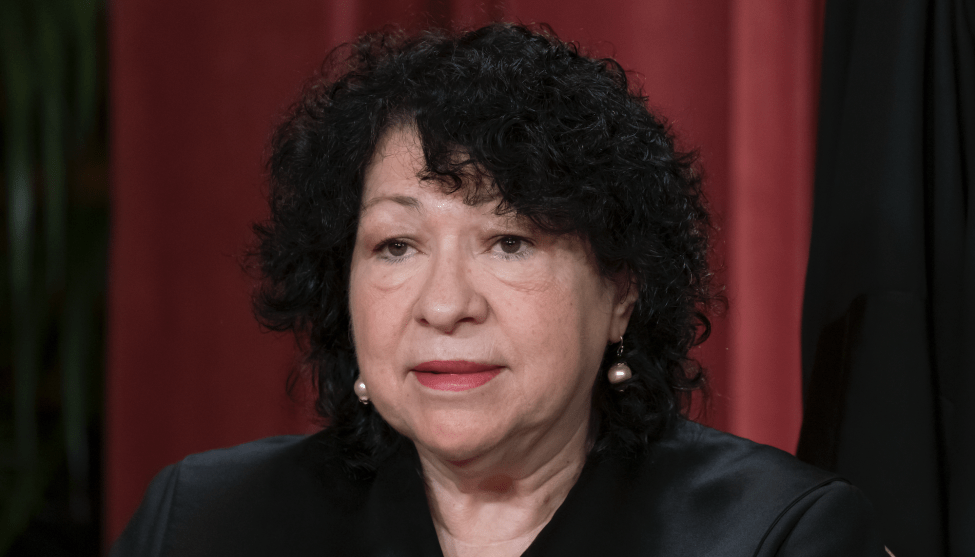

“The goal of the Pacific Legal Foundation and others in this extreme colorblindness movement is to take racial justice off the table as an objective for policymaking at all levels of government,” says Sonja Starr, a law professor at the University of Chicago who has closely followed the foundation’s cases. If the Supreme Court adopts this view, she warns, “it would be a legal earthquake.”

The Pacific Legal Foundation isn’t shy about the potential of the Thomas Jefferson case to have far-reaching effects. “The challenge in TJ is: Is your true purpose a racial purpose and are you trying to hide that racial purpose through race neutral means?” says Thompson. “That has universal application. That doesn’t just apply to universities, but it applies to high schools, it applies to contractors, it applies to employment.”

“The TJ opinion will just simply reach a lot more areas,” he says.

Not only are Thompson and PLF asking the Supreme Court to go much further than it was willing to in June, they are also seeking to have it take a big step away from its own precedents. While the court has rejected “racial balancing”—the goal of matching a student body to the demographics of the community—for decades it has held that boosting diversity is a compelling interest for colleges and universities as well as K-12 schools. And far from condemning race-neutral and race-blind policies that seek to minimize racial disparities, the court has encouraged such policies, particularly in K-12 schools.

While the Supreme Court’s recent affirmative action decision ended college admissions policies that use race as a plus factor, it did not formally upset its holding that diversity is a compelling interest, nor rule that it is an impermissible one, nor condemn race-neutral means to achieving it. It only held that Harvard and UNC failed to use race in a constitutional manner. While the practical implications of the decision will make it harder—if not impossible—for colleges and universities to weigh an applicant’s race in admissions, the goal of diversity so far remains good law.

Several civil rights experts expressed skepticism that the court would be willing to use the Thomas Jefferson case to undo decades of precedent. “If what you do is tell TJ they cannot adopt race neutral measures that open up opportunity for more students,” says University of South Carolina law professor Derek Black, “then what you’re saying is ‘We’re gonna block anything that somehow or other benefits Black people.'”

“That’s a bridge too far,” Black, an education expert, concludes.

But the current court has shown a willingness to overturn precedent, embrace radical decisions, and rule more like partisan actors than jurists. The TJ case would present yet another test showing how far the conservative majority is willing to go.

June’s Harvard and UNC decision, which kept diversity as a compelling interest, was fashioned by Chief Justice John Roberts. In the wake of attacks on the court for discarding long-held legal doctrine—most notably the right to abortion under Roe v. Wade—Roberts threaded the needle, effectively ending race-conscious admissions programs in higher education without explicitly overruling precedent. “He gets to have his cake and eat it too,” says Reginald Oh, a law professor at Cleveland State University. “He gets to basically abolish affirmative action while saying he did not.”

If Roberts had taken racial diversity off the table it would signal a much easier task for the Pacific Legal Foundation, which wants the court to adopt the position that working to increase racial diversity should be unconstitutional. Instead, he called it a “commendable” goal.

But elsewhere in the opinion, Roberts seemed to sympathize with PLF’s mission by stressing that the purpose of the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause was to create a colorblind society—a conclusion the court’s liberal dissenters, who instead argued the clause was meant to create an equal society, resist as harmful and ahistorical. “The equal protection clause is not intended to be a bulwark for the status quo,” explains NAACP Legal Defense Fund attorney Michaele Turnage Young, even though in the Harvard case, it served as one.

The June decision was not the first time the court struck down an admissions policy that took students’ race into account, and may not even be the best guide for how today’s court might rule in the Thomas Jefferson case. In a fractured 2007 opinion authored by Roberts, the Supreme Court invalidated two public school desegregation programs that weighed racial identity. That opinion seemed hostile to integration plans that used race, but a majority of the justices held that public primary and secondary schools are allowed to consider both the educational benefits of diversity and the negative effects of racial isolation. (Roberts did not join that part of the decision.) In the wake of the ruling, public K-12 schools largely opted to pursue racial diversity through policies that do not take individual students’ race into account. The TJ case and other similar ones seek to overturn this framework.

In December 2020, the county school board put its new Thomas Jefferson admissions regime in place. It jettisoned a $100 application fee and standardized test, which it worried acted as barriers to poorer applicants. In their place, TJ would use a more holistic review, including a problem-solving essay and a self-assessment of social skills like communication and collaboration, alongside their special education status, whether they are economically disadvantaged, and whether they’ve had to learn English. Most spots are reserved for applicants with GPAs that put them in the top 1.5 percent of 8th graders at each of the district’s middle schools. Unfilled spots would go to the strongest remaining applicants, judged on the same factors, with an additional boost for students from middle schools with weaker records of sending graduates to Thomas Jefferson. Importantly, the policy was not just race-neutral, but race-blind: no admissions officer knew the race of any applicant.

In March 2021, the Pacific Legal Foundation sued amid the selection of the class of 2025, alleging the new policy intentionally discriminated against Asian Americans in violation of the constitution’s equal protection clause. Citing statements by school board members, the superintendent, and TJ’s principal, the suit argued officials acted with animus toward Asian Americans, and pointed to an expected reduction in Asian American students as evidence that the policy would have a disparate impact on them.

The class of 2025, the first admitted under the new policy, did see Asian American enrollment drop from 73 percent to 54 percent. But it was more diverse. The share of Black students grew from 1 to 7 percent; Hispanic enrollment grew from 3 to 11 percent. White enrollment also ticked up from nearly 18 percent to 22 percent.

Some Asian American applicants fared much better: according to court records, the number of low-income Asian American students grew from just one to 51. Indeed, county figures show that the biggest beneficiaries of the new policy were low-income students, with their share shooting up from 0.6 percent to 25 percent.

The following year, numbers of Black and Hispanic freshman slightly declined, while Asian American enrollment grew toward 60 percent. As Starr notes in a forthcoming law review article, “if this was an anti-Asian policy, it was a remarkably ineffective one.” Nonetheless, in February 2022, Claude M. Hilton, a Ronald Reagan-appointed federal district judge, ruled in favor of PLF and the Coalition for TJ.

The Fairfax County School Board, now represented pro bono by Donald Verrilli, a former solicitor general in the Obama administration, appealed. His first task was to immediately ask the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals to stay Hilton’s decision; TJ was deep into selecting its 2026 class with no way revive the standardized test. He succeeded, allowing the policy to remain in place. When PLF asked the Supreme Court to reverse that ruling, the high court declined to hear their case. But in an indication that at least three justices would be sympathetic to PLF’s arguments, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, and Clarence Thomas dissented.

This May, in a 2-1 decision, the 4th Circuit formally reversed Judge Hilton and ruled for the school board. The policy, it found, did not have a disparate impact on Asian Americans, nor was it a product of intentional discrimination. The court ruled Hilton had erred in multiple ways, including by adopting an analysis that simply compared the percentage of Asian American students before and after the race-neutral policy’s implementation. “That approach would simply turn ‘the previous status quo into an immutable quota,’ thereby opening a new policy that might impact a public institution’s racial demographics—even if by wholly neutral means—to a constitutional attack,” the court wrote, quoting the school board’s brief.

The TJ case is one of several currently being litigated by the Pacific Legal Foundation, all alleging that changes in admissions policies at elite public schools violate the equal protection clause by discriminating against Asian Americans. The first arose in New York City in 2018, when it sued to block a policy to create more economic and racial diversity in the city’s specialized high schools by expanding space reserved for students from low-income middle schools. The foundation lost that case in district court and is awaiting a decision on appeal. In 2020, PLF challenged a new admissions policy for selective middle schools in Montgomery County, Maryland, again alleging it intentionally discriminated against Asian Americans. That case is now itself before the 4th Circuit. The foundation is also suing to admit several students to prestigious Boston schools who were denied entry under a plan the group claims was discriminatory.

Last year, America First Legal, a conservative group founded by former Donald Trump adviser Stephen Miller, filed a similar case in Philadelphia. Litigated with the help of Jonathan Mitchell, the former Texas solicitor general who orchestrated Texas’ infamous bounty-hunter abortion ban, the group alleged that a newly created admissions lottery for Philadelphia’s elite public high schools that gives a leg up to students from under-represented zip codes is a form of racial balancing. The suit remains in district court.

Starr calls this wave of litigation the “canary in the coal mine,” and describes the legal question it raises as “the likely future of litigation in the educational diversity space after the [affirmative action] cases.”

That’s because “colleges are likely to do very much the same thing that TJ and other public magnet schools at the K-12 level have,” Starr explains, and turn to race neutral policies that still stand to increase racial diversity. The cases will help determine whether that remains a viable—and legal—path.

The Supreme Court’s June decisions breathed new life into the broader push to block schools and businesses from promoting diversity—efforts that go beyond what the decision actually mandated. By the end of that month, America First Legal sent a letter signed by Miller threatening 200 law schools with legal action if they did not “immediately announce the termination of all forms of race, national origin, and sex preferences in student admissions, faculty hiring, and law review membership or article selection.” It sent similar warnings to nearly every medical school in the country and has threatened “woke corporations, law firms, and hospitals.” The group provides an intake form and toll-free hotline for workers who who think they’ve been “victimized by woke politics”—indications the outfit is looking for a plaintiff to challenge the constitutionality of job-based diversity, equity, and inclusion programs.

Ed Blum, whose group Students for Fair Admissions was behind the successful suits against UNC’s and Harvard’s affirmative action policies, emailed 150 colleges unsolicited directions for complying with the court’s new dictates, telling them to not only enact bans on considering race when selecting their student body, but to block admissions staff from reviewing applicants’ race—either individually or in aggregate. In July, 13 Republican state attorneys general similarly fired off a letter warning Fortune 100 businesses against weighing race in hiring, promotions, and contracting. But according to David Hinojosa, an attorney at the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights who argued against Blum’s group at the Supreme Court, demands for an entirely race-blind admissions or hiring process are not required by the court’s opinion. Given what the court actually held, Hinojosa says such tactics demonstrate cynical overreach: “They’ll try and leverage whatever they can to ensure that power remains in the hands of white people in America, especially white males.”

While these missives overstate the breadth of the Supreme Court’s affirmative action ruling, they accurately capture the intent of the next phase of their movement, one that targets not just race-conscious policies—but almost any attempt to increase diversity.

The recent affirmative action ruling doesn’t directly bear on the TJ case. “The Supreme Court’s decision in the Harvard-UNC cases does not have direct precedential value for race neutral programs at all,” says Turnage Young, who has represented civil rights groups in the TJ case. “That question was not before the court.” But in a press release, PLF signaled both its coming strategy and its optimism that the magnet school cases are the court’s logical next step: “the fight for race-blind admissions will persist, as universities are expected to pivot to ‘proxy discrimination,’ using facially race-neutral factors to achieve desired racial outcomes.”

Indeed, Roberts’ June opinion did sound some notes that Thompson and the Pacific Legal Foundation can take heart in—even if they aren’t formal legal holdings—including the chief justice’s view that the equal protection clause envisions a colorblind society. The debate over the clause’s meaning ran through several cases the court heard last term, and the conservatives’ perspective is central to PLF’s contention that the goal of diversity is unconstitutional. While that view has never been endorsed by the Supreme Court, it is a proposition at least several current justices may be willing to accept.

Roberts’ decision also used a phrase that PLF has deployed in its TJ case—“zero-sum”—to portray a scenario where a Black applicant who got a leg up in admissions due to affirmative action necessarily disadvantages a white applicant who did not. Lawyers for PLF plan to ask the court to extend that logic to race-neutral policies that foster diversity, arguing such changes are also a “zero-sum” form of discrimination: that any policy boosting Black and Latino enrollment intrinsically harms some other racial group. As the Fourth Circuit has already pointed out, the fact that a given policy somehow changes a school’s demographics is not in itself enough evidence to win a discrimination claim. But the argument will have at least a few sympathetic ears at the high court.

Finally, Thompson points to the end of Roberts’ decision, where the chief justice suggested he wouldn’t tolerate policies that seek to work around his affirmative action ban. What “cannot be done directly cannot be done indirectly,” he wrote, explaining that his ruling prohibiting race-conscious admissions is “leveled at the thing, not the name.”

That line, says Thompson, casts doubt that the court would agree with “the idea that you can adopt racial proxies to achieve a racial purpose.”

“And in that respect,” he says, “Harvard anticipates TJ, even if it doesn’t directly speak to it.”