Mother Jones illustration; Don Emmert/AFP/Getty

Recently, prosecutors got their wish. Though Judge Analisa Torres didn’t directly disqualify Bove, she did impose restrictions on the defenses Wang could mount if Bove continued as her attorney. After consulting with a court-appointed lawyer, Yang elected late last month to get a new attorney.

Federal prosecutors routinely work to ensure defendants are informed of lawyers’ potential conflicts, in large part to guard against issues that could be raised in an appeal. But former prosecutors told Mother Jones that efforts to actually disqualify defense attorneys are rare. “I can’t say that I’ve ever seen that,” said a former Southern District assistant US attorney who asked not to be identified. “That’s a big deal.”

Prosecutors’ effort to boot Bove from the Guo case had another important consequence: It revealed the existence of the counterintelligence probe into Guo’s foreign ties—an investigation that would normally have been kept secret. The outcome of that probe is unclear. It has not resulted in any criminal charges. Justice Department counterintelligence probes, unlike criminal inquiries, are not aimed at solving crimes but are instead intended to combat foreign espionage and protect US intelligence secrets.

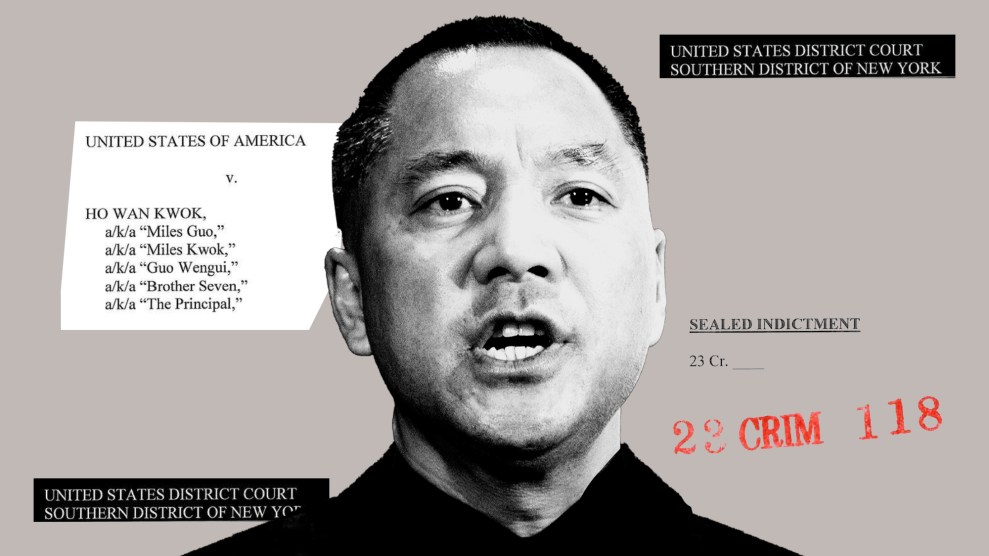

The court filings do not specify which of Guo’s foreign entanglements the FBI was looking into. But Guo, who arrived in the US in 2015 after fleeing imminent criminal charges in China, has been dogged by accusations—including in lawsuits by former allies—that he has secretly functioned as an agent for Chinese intelligence. In a letter included as part of a 2020 lawsuit against Guo, a large group of Chinese immigrants, including prominent critics of the Chinese government, alleged that Guo is “known to be an agent of China’s secret police.” In a 2021 ruling in a different lawsuit, related to a business dispute, a federal judge wrote: “The evidence at trial does not permit the Court to decide whether Guo is, in fact, a dissident or a double agent.”

Guo has denied those allegations, noting his outspoken attacks on the CCP have actually make him a top enemy of Chinese spies. (There seems to be some truth in those claims. An indictment this year of 44 employees of a Chinese-government-run social media troll farm alleged that they had standing orders to combat the online claims of a “Victim 1,” who is clearly Guo.) A lawyer for Guo, who is being held without bail in a jail in Brooklyn, did not respond to questions.

Within months of arriving in the US, Guo joined Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago club in Palm Beach. Guo began to publicly rail against the Chinese Communist Party in 2017, issuing colorful, though largely unsubstantiated, allegations about corruption among top Chinese officials. Guo’s credibility as an anti-communist dissident got a big boost from press reports revealing Chinese efforts to secure his extradition. A roster of powerful Americans—including casino mogul Steve Wynn, Trump fundraiser Elliott Broidy, and even hip hop artist Pras Michel—were accused of secretly assisting the Chinese extradition effort.

Guo’s rhetoric quickly won him enthusiastic support from large numbers of Chinese emigres, many of whom he is now accused of defrauding by embezzling funds they invested in his business ventures. Guo’s public anti-CCP stance—along with his wealth—also helped him forge relationships with Trump-linked CCP critics, including Bannon, Giuliani, and Jason Miller, who is now a top aide for Trump’s 2024 campaign.

The recent DOJ filings reveal that at the same time Guo was cozying up to powerful figures, the FBI was scrutinizing Guo.

Guo applied for political asylum in the US in September 2017. According an August 2023 filing by prosecutors in the fraud case, from April 2018 until May 2019, Guo “voluntarily provided information” to the FBI “in the hope of receiving assistance with respect to his US immigration status.” The New Yorker reported last year that Guo gave the bureau information on “Chinese leaders’ financial and private lives.”

The public part of the motion prosecutors filed does not say why Guo stopped talking to the FBI in 2019. But it makes clear that by that fall, Guo had gone from an FBI source to an investigative subject. The document—which includes a classified supplement and lengthy redactions—indicates that Southern District investigators opened a “matter” related to Guo on September 8, 2019. On October 3, they executed search warrants at Guo’s residence in Manhattan’s Sherry-Netherland hotel and his nearby office. Agents seized “more than 100 electronic devices and documents that were stored inside safes,” the filing says. Redactions of ensuing lines obscure what may be a more detailed description of the material the agents found, but the filing indicates that the investigation continued into at least the fall of 2020.

Prosecutors point this out to show that Bove, who supervised attorneys who drafted the search warrants, was involved in the case. They also cite emails that indicate Bove was aware of the separate fraud investigation into Guo, launched in May 2020, that resulted in the arrests of Guo and Yang earlier this year. Bove left the DOJ in December 2021.

Bove, who did not respond to inquiries from Mother Jones, disputed the government’s claims. He said in court filings that his involvement in the counterintelligence probe was not substantial and that the probe was not closely related to the criminal case in which Guo and Yang are now charged. Bove also seemed to add a bit of information. He said that the feds who conducted the searches were, specifically, “counterintelligence agents from the FBI.”

The government’s filings suggest Guo’s foreign connections went beyond his alleged links to China. The DOJ noted on August 9 that subsequent searches related to Guo’s March 2023 arrest turned up a report, stored in a safe, indicating that Guo in October 2018 had met with officials from the United Arab Emirates to help them prepare for a meeting with Chinese counterparts.

What the FBI may have learned about Guo’s foreign links remains a secret. But the fact that the feds were investigating at all is striking, given the people Guo has had on his payroll.

Guo paid Bannon $1 million for “strategic consulting services” under a year-long contract that ended in August 2019, Axios has reported. By then Bannon had been working with, and for, Guo for a few years. The one-time Trump strategist met Guo shortly after being ousted from the White House in 2017. He quickly began helping Guo launch nonprofits, media companies, and other ventures. These entities were all part of an intricate effort, the pair claimed, to “take down the CCP.” Bannon also advised Guo in 2020 on a private stock offering, along with other financial ventures, that figure prominently in the DOJ fraud case against Guo. Bannon is not charged with wrongdoing in that matter.

Guo even offered Bannon use of a private plane, a Connecticut house, and a luxury yacht where Bannon was living when he was arrested in a separate case in 2020. Since then, Bannon has remained close to Guo. As recently as last year, Bannon aggressively promoted the financial ventures that Guo allegedly used to scam investors.

Giuliani—while serving as Trump’s personal lawyer in 2020—worked closely with Guo and Bannon to distribute lurid material from Hunter Biden’s laptop. Guo, or companies he controls, paid Giuliani and Michael Flynn, Trump’s former national security adviser, $50,000 each for speeches in 2021, a person familiar with the payments said. Peter Navarro, a Trump White House aide, has also worked for a group, the New Federal State of China, that Guo and Bannon set up. It’s not clear if Navarro was paid for that work. Giuliani, Flynn, and Navarro did not respond to requests for comment.

For his part, Miller received $750,000 per year, along with a $250,000 annual bonus, while working from 2021 until February of this year as CEO of Gettr, a right-leaning social media site in which Guo has played a major, though disputed, role. Miller worked directly with Guo at Gettr, where Guo often gave orders to top IT executives. Federal prosecutors asserted in March that Guo “controls Gettr through a series of shell companies.”

Gettr disputes that. “Guo was not and is not an investor in GETTR,” the company said in a statement Friday. Guo, Gettr said, “was one of the top influencers and content creators on the platform.”

A person familiar with Miller’s thinking said that he received assurances prior to signing on as Gettr’s CEO that “not one penny of Guo’s money” was invested in the company. The person added that Miller was told by two former Trump administration officials that Guo “was a target of the CCP” and that Guo was not advancing CCP interests in the US.

Bannon did not respond to questions. But he has previously suggested that Guo’s anti-communist rhetoric was more important than any ties Guo might have with some entity connected to the Chinese government. “He’s done more than anybody to wake this country up to the threats of the CCP,” Bannon told the New Yorker last year. “Whether he’s working for a faction or he’s hedging his bets, the stuff he’s done and what he’s galvanized is just relentless.”