You can track QAnon’s arc, like most things in America, through its relationship with corporate brands. Although the conspiracy movement emerged out of fringe imageboards in 2017, its first viral successes came on Facebook and YouTube, where its lore envisioning Donald Trump fighting an elite cabal of liberal pedophiles was honed and refined. When Covid came in 2020, QAnon ballooned under lockdowns, putting it in the mainstream, but leaving it short of actually being mainstream.

Call it the Wayfair era. In July 2020, followers of QAnon began spreading a particular pedophilic panic: the absurd notion that the online furniture retailer was selling children for sexual abuse via armoire orders. Non-Q masses took the bait: “Mentions of Wayfair and ‘trafficking’ have exploded on Facebook and Instagram over the past week,” the Associated Press wrote at the time, noting that related TikTok hashtags “together amassed nearly 4.5 million views.” A national human trafficking hotline issued a press release warning that a flood of calls about the conspiracy had distracted them from genuine work.

While it was widely peddled, it was also widely derided. Surely, something so absurd could not keep going. And looking back on the uproar from two years later, Wayfair seemed like the death of Q. By late 2020, major Q adherents had been purged from the platforms. Its influencers and weird hoaxes almost never broke into broader consciousness, except to be debunked. Its galvanizing messiah, Trump, was on his way out of the White House. Q was no longer inspiring people to murder mob bosses, kidnap their own children, or show up heavily armed at the Hoover Dam.

But far from being the end, Wayfair was a sign of what the movement was turning into—one confirmed in late November 2022, when the Balenciaga panic happened. The genesis point was a TikTok video posted by Brittany Venti, a right-wing provocateur and influencer with a history of aggravating culture war fights. While displaying pictures from a Balenciaga ad campaign showing small children with purses made to look like teddy bears wearing bondage straps, she complained that a “worldwide, internationally known brand” was “advertising their purses by having a child hold kink fetish gear.”

We are in an era of obsessive, odd, and sprawling fear of pedophilia—one where QAnon’s paranoid thinking is no longer bound to the political fringes.

“To me, it’s about sexualizing children,” Venti concluded in the video, which garnered millions of views. Popular YouTuber Shoe0nHead relayed the complaint on Twitter, adding the claim that the photo shoot had “included a very purposely poorly hidden court document about ‘virtual child porn.’” Her tweet took off, boosted by large right-wing accounts, including the notoriously transphobic Libs of TikTok. Together, these influencers—none of whom maintain explicit links to the Q movement—galvanized masses of people to throw up their arms in disgust. As right-wing influencers like Candace Owens and Andrew Tate seized on the Balenciaga panic and dolled it out to their audiences, it became one of the biggest stories on the internet.

For some, the conversation moved beyond the ads and into accusations that the campaign somehow captured a reality that children were being abused by Balenciaga. A Twitter user accused Balenciaga of “getting even sloppier about their underworld.” “Pedophiles telling us they’re Pedophiles RIGHT IN OUR FACES,” another wrote.

It was Wayfair again, but bigger. And like Wayfair, it didn’t make sense and wasn’t true. Bondage may have been intractable from BDSM in the ’70s, but it had long since been co-opted by other subcultures, like techno ravers, artists, high fashion, and anyone interested in cosplaying as subversive. The court documents hadn’t appeared in the campaign alongside the children, but in a separate one featuring adult women. And of course, there was no child abuse. The photographer who did the shoot was well known for his not-at-all-lewd documentary work, and his subjects were the kids of Balenciaga employees who were on set supervising.

The episode revealed that the paranoid thinking of QAnon hadn’t disappeared, but that its logic was influencing people far beyond the reaches of the conspiracy theory. The Wayfair panic had been partially incepted and egged on by QAnon boosters. The Balenciaga panic was not. But their contentions were the same: Liberal elites were molesting kids and were brazen enough to leave clues in plain sight.

The Balenciaga panic can be seen as QAnon by other means—a mainstreamed version that imagines threats to children lurking just about everywhere. The long history of moral panics has often centered on seeing attacks to “the family” as social progress reaches schools, libraries, and hospitals and challenges old moral foundations. To prove it, they say, one need only need to pay attention, and to stand by is to allow an attack on children. Think of the Christopher Rufo–bolstered critical race theory panics, drag brunch panics, transgender panics, LGBTQ panics. They’re all at least partially incubated in the same petri dish as Q: paranoid nightmares dreamt up during moments of a changing social order.

It would be easy to cast all this aside as the horrific, confused ramblings of the stupid. But that ignores a central, uncomfortable fact: Many of us act like Q adherents now. While the movement itself has been thrown away, its styling is now dominant. We are in an era of obsessive, odd, and sprawling fear of pedophilia—one where QAnon’s paranoid thinking is no longer bound to the political fringes of middle-aged posters and boomers terminally lost in the cyber world.

Yes, many of those people thought that Balenciaga was advertising an actual role in a child sex cabal. But others did, too, as elements of the Balenciaga panic attained a level of mainstream acceptance that the Wayfair scandal never had. Cooper Kupp, the 2022 Super Bowl MVP and a generally apolitical wide receiver for the Los Angeles Rams, encouraged his Twitter followers to “please make yourself aware of the attack against our young ones,” accusing Balenciaga of “advertis[ing] evil.” Yashar Ali, a prominent left-leaning writer and journalist, called the campaign “gross” and praised an organization for revoking an award it had given to the Spanish fashion house. Kim Kardashian, who had never complained about any issues regarding child abuse or pedophilia over the years as she wore Balenciaga to high-profile events and its fall 2022 runway show, began hammering the brand. “As a mother of four,” she wrote in a statement, “I have been shaken by the disturbing images.”

Caroline Busta is a writer and critic who, with her partner and pseudonymous fellow critic Lil Internet, runs New Models, an internet community, website, and podcast. They closely watched Balenciaga-gate ensnare their interests—the intersection of fashion, the internet, politics, and media studies—a moment Lil Internet said felt like a breaking point. “It was the first time I saw the far right pull off a troll campaign that actually just got all of mainstream media—and even, like, progressives,” he said during a joint interview with Busta. Venti’s role kicking off the controversy, he added, “should be all the evidence anyone needed to question it.”

The Balenciaga uproar was a clear marker of Q’s successful diffusion, but it wasn’t the only one. Around the same time, decades-old drag brunches and the over half-a-decade-old drag queen story hour were suddenly identified as loci of child sex crimes. Instances of hospitals that treat transgender children being inundated with threats, libraries closing, schools calling off events, cafes canceling drag brunches, and things as odd as butterfly sanctuaries having to close because of threats over human trafficking conspiracies became commonplace. Such occurrences are now so regular that they barely register beyond the communities where they happen.

Or, as Travis View, a host of the QAnon Anonymous podcast and an independent researcher of the conspiratorial right, puts it, “There is a sense in which QAnon won.”

Indeed, Republicans who assiduously avoided QAnon during its initial runup now find it expedient not only to make overtures to it, but to pursue attacks and policies that jibe with its obsessions.

Last June, after Trump had already taken to donning a QAnon lapel pin and amplifying the conspiracy on social media, the Conservative Political Action Conference Foundation launched the Center for Combating Human Trafficking. While competing for the GOP’s 2024 nomination, Trump floated the death penalty for human traffickers and insinuated that Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis was a pervert and possibly a pedophile. During Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson’s 2022 confirmation hearings, Sen. Josh Hawley (R-Mo.) smeared her as having a “pattern of letting child porn offenders off the hook” as a judge. Marjorie Taylor Greene’s entire career trajectory from being an ostracized QAnon congresswoman to cementing a position as one of the most prominent right-wing politicians in the country is itself a demonstration of the mainline GOP coming to terms with the conspiracy.

“QAnon made space for more popular conspiracism on the right,” says View, explaining that it gave an opportunity for people like Chaya Raichik, the woman behind Libs of TikTok, to present conspiracies more palatable to the mainstream. Take so-called “groomer narratives,” View says, which “aren’t quite as crazy as QAnon” even though they are destructive and libelous.

The idea that left-wing child sex predators are omnipresent in schools has obvious echoes with the idea that lefty elites are running a massive pedophile ring. And both have a kernel of truth: Wealthy liberals were in Jeffrey Epstein’s orbit, and occasionally teachers are outed as predators. But neither has happened to the degree that Raichik et al. and QAnon allege—nor do they happen along the rigid lines they imagine. Epstein’s contacts spanned the political spectrum, and few are under suspicion of being involved in his abuse; and, of course, the majority of offending teachers are not gay or trans.

This paranoia has real effects: In 2023, legislators introduced 615 anti-trans bills—a threefold increase from 2022, according to the Trans Legislation Tracker. Every year since 2021 has set new records in the number of books banned, with many titles being contested over perceived pro-LGBTQ stances. The authors are often baselessly accused of being “groomers.” It’s a practice that jibes with how, as QAnon’s ethos spread to other forms, people began to “find” pedophiles in all sorts of places they verifiably weren’t.

It has even happened to me.

Last July, I opened Twitter to see that I had nine notifications. I hadn’t posted anything of consequence recently, but when I clicked through the alerts, I saw people calling me a pedophile and saying they wanted to do violent things to pedophiles. Someone using the handle 1776andBeyond (1777?) tweeted at me that “the only good pedophiles are dead ones.” A guy named Simeon tweeted that I was “legit pedo” (as opposed to a fake one?). Someone had photoshopped me onto a figure kneeling in front of an SS officer with a Pepe face and a pistol pointed at the back of my head. Another person tagged me in a post with the words “PEDOPHILES BELONG IN WOODCHIPPERS” over the image of a stick figure being fed into a machine with pink mist coming out. Similar emails came in from people who wanted to threaten me, but were too shy to do so in public.

After some clicking and scrolling, I found the inciting post: An account called End Wokeness that boasted 1.4 million followers had tweeted a screenshot of the headline on an article I wrote in 2019 (“Why Are Right-Wing Conspiracies So Obsessed With Pedophilia?”), next to photo of a small child holding a rainbow flag, interacting with some men dressed in dog fetish wear, possibly at a pride event. I had entered a Stoppardian, play-within-a-play situation: In my work writing about the right hallucinating about there being pedophiles everywhere, I briefly became a right-wing pedophile hallucination.

A smaller version happens to me every couple of months, as other accounts post mocking screenshots of the same story. As my repeated experience shows, at some point between the first Q drop on 4chan in 2017 and last summer, people, including many who didn’t believe or endorse the QAnon movement’s fantastic claims, had nonetheless become so primed to find pedophiles that anyone who came across their feed was potentially abusing children.

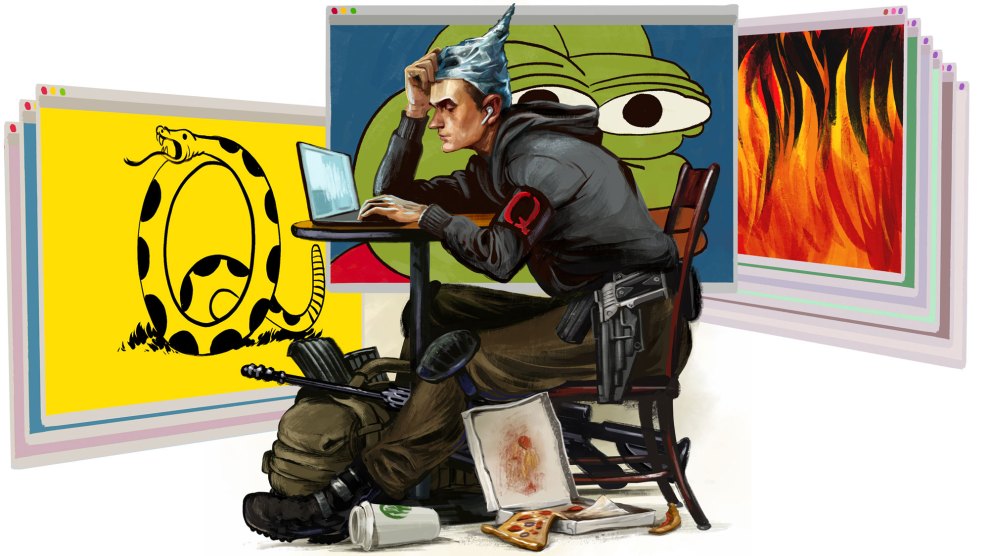

QAnon’s spread was aided by its conjoining—beneath hamfisted and lurid conspiracies—of transphobia and the Q faithful’s fear of losing their position in a changing social order. A key part of the QAnon eschatology is “The Storm,” also known as “The Great Awakening”—a fantasized judgment day that ushers in mass arrests of liberal elites and a purge of their deep state minions, opening the path for a new golden age of conservative government that embraces the nuclear family and the return of classic, white, Christian family values.

In 2019, while reporting that essay about the right’s obsessions with pedophilia, I reached out to View, who had recently started his podcast observing the Q phenomenon. Libs of TikTok didn’t yet exist, armed gunmen weren’t showing up to drag brunches, and DeSantis, just elected governor, had yet to launch his harshest attacks on Florida’s trans community.

Against that backdrop, Q felt confined to its conspiratorial fringe. View explained that there was “a great deal of anxiety” in the QAnon community about LGBTQ rights and trans rights in particular. “They’re concerned generally on the sort of acceptance of trans people and the over-sexualization of children,” View said, explaining that the movement hadn’t quite figured out how to integrate the issue into its attacks on liberal elites and its fantastic claims about underground pedophile rings.

We also discussed the QAnon economic vision. “One thing they often talk about after ‘The Storm’ is that they imagine that the economy will be restored so that a single income can support a family again,” View told me. “They imagine traditional gender roles and norms will be upheld and how children are raised will return to what used to be.”

It was one of the first times we spoke, and neither of us understood just how far QAnon would go, or that its adherents would eventually help establish a messy new grammar with conjunctions that, in a time of economic and cultural anxiety, combined all of these things: a cabal of liberal elites running a child trafficking ring. This same group of people was also pushing a “gay agenda” and “gender ideology” that elevated trans people, who were “grooming” children, with the verb’s meaning flipping as convenient between literal pedophilic grooming and indoctrinating kids to be trans, or to simply be okay with people who are.

Public figures who embrace the traditional atomic family—like DeSantis, Raichik, and Rufo—smoothed out the grammar that Q established into more palatable versions, as people wholly unconnected to QAnon used this echoing rhetoric. Serial plagiarist Benny Johnson likes to call President Joe Biden a groomer. Fox News’ Laura Ingraham has claimed public schools are sites of grooming. Republican lawmakers introduced anti-grooming legislation. Roger Stone recently accused 2024 GOP Senate candidate Larry Hogan, Maryland’s former governor, of having a “record of involvement with pedophiles.” This language now extends beyond politics. When rapper Kendrick Lamar puts out diss tracks accusing his rival Drake of being a pedophile, he makes the connection explicit: “I’m lookin’ to shoot through any pervert that lives, keep the family safe.”

QAnon’s clearest precedent was the Satanic Panic of the 1980s, another set of lurid beliefs about child endangerment that surfaced amid a changing social order in response to perceived threats to the nuclear family. Four decades ago, it happened at preschools—a tool aiding women transition away from homemaking and into the workforce—as caregivers were accused of waging demonic abuse against children.

Today, QAnon exists in a vastly more complex media ecosystem and seems to be addressing a wider, more amorphous set of concerns. But its rough function is the same: The family order is again seen as being threatened, this time by attacks on gender norms. Q gives people a way to feel they are protecting the traditional atomic family. By devouring fresh posts from QAnon influencers, donning Q gear, or spreading word online about the impending arrest of the cabal, Q faithful felt like they were doing everything they could to support the welfare of children and usher in a new era of conservative family values that would put them in charge.

The primacy of family in contemporary American reactionary politics made this sentiment appealing to non-Q-pilled conservatives, once the weirdest, most absurd parts were pushed into the background. The family is often assumed to be self-evident—especially on the US right—as the ideal social formation of a proper Christian nation. Instead of being bound together by a government helping us all, the belief goes, we are better served by little kin units tending to their own. The roots of the idea lie much further back than Margaret Thatcher, but a line she said in 1987 makes the point: “There’s no such thing as society. There are individual men and women and there are families.”

She and Ronald Reagan spent their tenures as heads of state pursuing policies linked to this credo, but their belief in the family didn’t only stem from Christian religiosity. They understood that an atomized society with weak ties beyond the family is better for business.

As the UK’s prime minister, Thatcher stoked interclass hostilities by pushing private homeownership. As historian Melinda Cooper explained in her 2017 book, Family Values, by owning a home, swaths of the British white working class had a stake of capital instead of being at odds with it—a nest egg that would “would teach the working class the value of inherited wealth and wean them off public services.”

In the US, Cooper notes, advocates for the privatization of Social Security “explicitly sold these instruments as vehicles of familial wealth accumulation.” These capital-aligned forces argued that Social Security pushed individuals toward the state and away from free markets—unlike stock market wealth, which they saw as “inheritable and would therefore serve to strengthen rather than undermine the bonds of family dependence.” By turning nuclear families into portfolios of housing equity and stocks, the right hoped to lock in votes favoring markets over the state. (Investors and money managers also expected to profit from their new, unsophisticated competition.)

Thatcher’s claim that there are only “men and women” is not an accident. Restrictive gender roles were, and still are, necessary to the world she envisioned. “The single biggest off-the-books investment that keeps stripped-down neoliberal economics working is free female labor,” historian Bethany Moreton told me. American women average over four hours a day of unpaid labor; some estimates put the annual value of this work at $1.5 trillion. If those hours were reduced or paid out, there would be massive cultural and financial repercussions. Men’s lives would be upended, as things stopped happening and they either faced the consequences or had to pick up the slack. Such changes would rewrite what it means to be a good wife and caring mother or, more fundamentally, popular visions of being a woman. Many people naturally will go to great lengths to not have to reimagine the fundamental basis of their lives.

“You’ve got a huge resource at stake: the continued ability to pass off gender as natural,” explained Moreton, a Dartmouth College professor and the author of Perverse Incentives: Economics as Culture War, a forthcoming book. Her point is that debates over gender binaries are also material claims and not just cultural ones. When people on the right declare increased acceptance of trans and nonbinary people as evidence of moral decay and the fall of the West, it is bigotry, but it is also because ending strict gender norms would demolish society as they conceive it. “They’re not shitting you when they say the world would come to an end, because their world would come to an end,” Moreton said.

Calling LGBTQ teachers “groomers” strikes a nerve, and claiming that trans indoctrination or critical race theory is getting in the way of learning important subjects like math and science strikes another at a moment of ever-increasing inequality, and as class struggle plays out on the field of college acceptances. If trans vitriol leveled at high school athletics hit in a broader way than the original bathroom-ban bills did, it may be because a kind of person would go crazy over the idea (however unlikely) of a woman losing an athletic slot at an elite college or a sports scholarship to a man they thought was indoctrinated into being a trans woman. To the white reactionary, it is the destruction of gender binarism, the sanctity of sports, and the myth of meritocracy all at once.

Fighting acceptance of trans people offers the potential to turn the clock back on traditional gender values and retreat toward the traditional nuclear family-based society that the right values—and that values them—and the free female labor that came with it. And it provides a field of argument where conservatives don’t have to baldly argue a system that operates on women’s unpaid labor should persist for the benefit of men.

While DeSantis, Rufo, and the like railed against elites they detested, the elites that they do like stand to benefit from socioeconomically isolated families and strained social ties of weakened labor power. If QAnon might have looked like a movement toward some bizarre future, it and the mainstream version that came after are, in truth, attempts to return to the past.

Update, July 26: This story has been revised with a new 2023 figure from the Trans Legislation Tracker, and to clarify the name of the Conservative Political Action Conference Foundation.