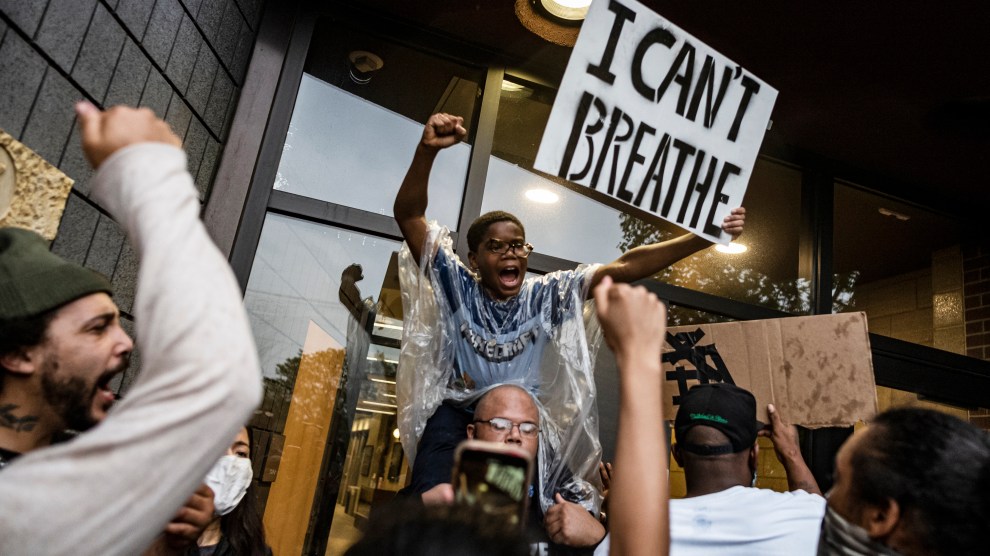

Mother Jones illustration; Getty

We may not yet know what the final tally of the presidential race will be, but when it comes to police reform, voters during this year’s election sent a clear message: It’s time to change how we think about public safety.

The nationwide protests that erupted this summer after the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and too many other Black men and women showed that activists aren’t messing around with their demands to hold cops accountable. And they took that energy to the polls. Across the county, there were at least 20 ballot measures dealing with law enforcement reform—more than in previous elections—and all but one of them passed. “All of this is just a culmination of the years of organizing that has happened by Black folks,” Chris Melody Fields Figueredo, who leads the nonprofit Ballot Initiative Strategy Center, told Bloomberg CityLab last month.

Voters overwhelmingly approved checks on the power of police, as well as measures designed to invest in alternative responses to the social problems like mental health and homelessness at the root of crime. Here are some of the policing issues they weighed in on, from Ohio to California to Texas:

Holding police accountable for misconduct

Police reform most frequently turned up on 2020 ballots in measures to strengthen police accountability, often by creating new government bodies to review complaints about police behavior or granting new powers to existing review boards. As election results came in on Tuesday and Wednesday, these initiatives proved overwhelmingly popular—voters approved them in at least 11 cities and counties in five states. None of the proposals earned less than two-thirds of the local vote.

In Portland, Oregon, for example, where anti-racist protesters clashed with police week after week this summer—and where police used tear gas and smoke grenades to crack down on demonstrators—82 percent of voters opted to dissolve the existing police review board. The new board created by Measure 26-217 will have sweeping powers to subpoena police documents, require officers to testify, and discipline or even fire officers, according to the Willamette Week.

And in Pennsylvania, two winning initiatives promise to strengthen oversight in cities with weak or historically ineffective review boards. In Philadelphia, where protests erupted last week over the fatal police shooting of Walter Wallace Jr., a 27-year-old Black man, voters authorized the city council to replace its old Police Advisory Commission with a new body—though it remains in the hands of city leaders if it will be better funded or more effective than the old one. Pittsburgh, meanwhile, voted to allow the city’s existing Citizen Police Review Board to compel police officers to cooperate with its investigations (the officers can now be fired if they don’t). The measure will also require police brass to wait for the review board’s recommendation before making final disciplinary decisions, theoretically allowing for some independent input.

Related measures passed by wide margins in Columbus, Ohio; Kyle, Texas; and in six places in California (Berkeley, Oakland, San Francisco, San Jose, Sonoma County, and San Diego).

Defunding the police

After the killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, demands for change in US policing shifted dramatically as activists called to strip funding away from police departments rather than reform them. City officials from Oregon to New York made some motions toward reducing police budgets, but little ultimately changed. While no ballot initiatives this year would have explicitly slowed the flow of taxpayer money into police coffers, measures in Los Angeles as well as DuPage County, Illinois, approached the question of police budgets indirectly.

Rather than defunding cops, the coalition of community organizers behind a Los Angeles initiative known as Measure J proposed investing in crime prevention and alternatives to incarceration. The measure, which passed with 57 percent of the vote, will amend the county charter to set aside 10 percent of all locally generated revenues (which totaled about $8.8 billion this year) for diversion, job training, mental health treatment, substance abuse counseling, and similar programs. None of the money can go to cops. LA Sheriff Alex Villanueva saw the proposal as a threat: “If you don’t want your streets to look like a scene from Mad Max, use your voice to tell the board what you think,” he tweeted this summer, as county supervisors were considering the initiative.

However, in the Chicago suburbs, the DuPage County advisory measures (which do not carry the weight of law) came at the issue from the other side, asking whether the county should “consider financial support of law enforcement and public safety its top budgeting priority” and “continue to fund and support training methods that decrease the risk of injury to officers and suspects.” Both passed with large majorities.

Limiting the number of police officers, or requiring them to be local

In the wake of Floyd’s death, Minneapolis city council members announced a bold plan to completely dismantle their police department. But they ran into a problem: They couldn’t fire all or even many of the cops, because the Minneapolis city charter mandated that they fund a police department with around 730 employees, based on the city’s population. And changing that charter would require a public vote.

The Minneapolis council members failed to get their proposal on this year’s ballot, so their city couldn’t vote on it. But they may have inspired changes elsewhere. On Tuesday, people in San Francisco decisively approved Prop. E, a ballot measure that will amend their city’s charter so that it no longer mandates a minimum of 1,971 full-duty officers on the force. Supporters hope this will make it easier to bring in other types of professionals, like social workers, to respond to 911 calls dealing with homelessness and mental health crises. The local police union predictably opposed the change, saying they were already understaffed.

In St. Louis, voters were also asked whether to amend part of their city’s charter dealing with the composition of their police department. This time, the question wasn’t how many officers could join the force, but where those officers could reside when they weren’t at work. The St. Louis charter currently requires cops to live in the city for at least the first seven years of their employment, something that critics say makes it more difficult to recruit and retain officers. In September, state lawmakers temporarily lifted those requirements, allowing cops to live elsewhere. Proposition 1 would have made that change permanent in St. Louis, but voters narrowly rejected it.

As we’ve previously reported, residency requirements for police are controversial. Around the country, most officers don’t reside in the city or town where they work, according to an investigation by USA Today. And some activists worry that when cops don’t live where they patrol, they feel less connected with and accountable to people on the streets, which theoretically could make them more likely to use force. After Floyd’s death, protesters in Philadelphia and elsewhere demanded residency requirements. But according to criminologists and grassroots groups cited by USA Today, including the Minnesota-based Communities United Against Police Brutality, there’s no recent research showing that cops who live locally are better at their jobs.

Better investigating police brutality

After a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, killed Michael Brown in 2014, activists around the country increasingly pressed for officers to wear body cameras, so their misconduct could be caught on film. But in the years since, these cameras haven’t been much of a fix: Too often, police departments refuse to release the video footage, citing an ongoing investigation. Or they delay doing so for months or years, until they’re forced by public pressure or a court order.

The voters of Akron, Ohio, were tired of that. They overwhelmingly passed a ballot measure that will require the police to “promptly” release body-cam recordings after an officer kills or seriously harms someone, as long as there’s no law preventing them from doing so. Research on whether body cams can positively affect police behavior is mixed, but supporters hope the change will at least make the department more transparent.

People in King County, Washington, which includes Seattle, also pressed for better investigations after police brutality. They passed Amendment 1, which will require investigations anytime a person dies in law enforcement custody, and will ensure the county pays for an attorney to help family members of the victim.

Restricting police searches

Following concerns that police officers in Michigan were collecting data from civilians’ cellphones using “Hailstorm” and “Stingray” devices, a Republican in the state House introduced a measure to write protections for digital data into the state constitution, according to Bridge Michigan. Under Measure 20-2, which was supported by about 9 out of every 10 voters statewide, police will have to get a warrant before accessing someone’s electronic data or communications. The measure follows similar successful initiatives in New Hampshire and Missouri, and codifies existing case law.

Meanwhile, Philadelphia voters overwhelmingly approved a local measure calling on police to end “unconstitutional stop and frisk” policing. While the measure won’t prevent officers from stopping and frisking a person they had “reasonable suspicion” to believe was committing a crime, it will condemn stops conducted for no reason but the subject’s race, gender, sexuality, or other protected characteristic. Reports released by the ACLU of Philadelphia this spring found that just between July and December 2019, Philadelphia police stopped about 6,000 people without reasonable suspicion. Overall, Black Philadelphians were stopped far more frequently than their white counterparts; they comprised 71 percent of those stopped and 83 percent of those frisked.

Limiting sheriffs

And let’s not forget about the sheriffs, whose deputies can help patrol the streets and respond to emergencies in many towns. Sheriffs are often elected to their jobs, but King County, Washington, residents passed a ballot measure to make theirs an appointed official—selected by the county executive and approved by the city council. Supporters of Amendment 5 argue that sheriffs who want to look good for reelection might not embrace thorough and independent investigations of their deputies’ misconduct. Critics worried the measure would remove people’s right to directly oust bad sheriffs. But it passed with 56 percent of the vote.

King County also approved a measure that lets the city council decide the sheriff’s job responsibilities, rather than letting the sheriff choose herself. Amendment 6 doesn’t allow council members to go so far as completely abolishing the sheriff’s department, but it does allow them to take away some of its duties and power. The goal is to put certain tasks, like responding to mental health crises, in the hands of trained health professionals, allowing sheriff’s deputies to focus more on responding to crime. Police unions spent hundreds of thousands of dollars trying to defeat both ballot measures.

“What they’ve been asking us to do is move away from [a] system of law enforcement that deploys armed police officers to respond to every situation, because that’s how you end up with dead Black and brown people, to put it frank,” council member Girmay Zahilay, who wrote one of the ballot measures, said last month. He promised to let families of people killed by law enforcement weigh in on the sheriff’s duties.