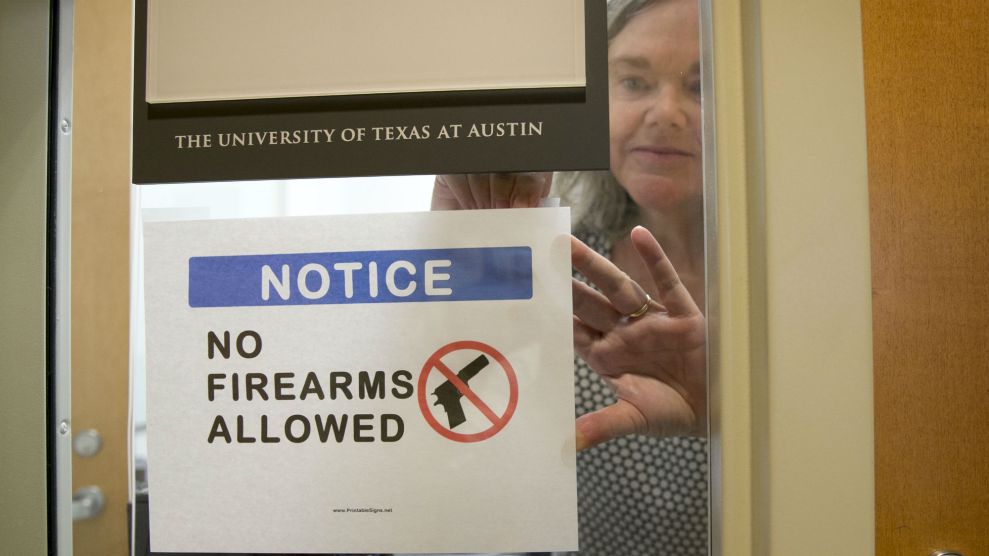

Students protest a campus carry law in Austin, Texas, in August.John Mone/AP

Eight states currently have laws that allow people to carry guns on college campuses. In 24 others, individual colleges can decide whether to allow firearms on the premises. The primary rationale for these laws, according to their supporters, is safety: School shooters, they say, are less likely to succeed in their attacks if students and teachers are armed and able to fight back.

But a new study from Johns Hopkins University shows that campus carry laws are unlikely to deter rampage shooters and may in fact lead to more injuries and deaths. Here are the main takeaways from the research:

Concealed-carry laws do not deter mass shootings

Advocates for looser gun laws have popularized the idea that armed criminals are more likely to attack in “gun free” zones where nobody can fight back against them. Colleges that ban students from carrying weapons are consequently more dangerous, according to proponents of campus carry laws. But this theory is not supported by data, the Johns Hopkins study found. From 1966 to 2015, only 12 percent of 111 high-fatality mass shootings in the United States—at college campuses or elsewhere—took place in “gun free” zones, and only 5 percent took place in “gun restricted” zones, where security guards were armed but civilians were banned from carrying weapons. Another analysis, published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, drew similar conclusions: Only 13 percent of mass shootings from 2009 to 2015 occurred in gun-free or gun-restricted zones. What’s more, allowing people to carry concealed weapons has been connected with an increase in violent crime, according to researchers at the Brennan Center for Justice. They noted a 10 percent average increase in violent crime in states that adopted right-to-carry laws.

Armed civilians are not likely to stop a rampage shooter

When a mass shooting does occur, campus carry advocates say, it helps to have responsible gun-toting civilians in the area, so they can thwart the attacker. Pro-gun economist John Lott and other advocates point to 39 incidents where they say armed civilians have helped stop gunmen. But when the Johns Hopkins researchers looked into the cases, they found that only 4 of 39 actually involved an armed civilian stopping a rampage shooter. What about the other 35 alleged incidents? As with various past cases debunked by Mother Jones, they did not stand up to scrutiny: Twenty-two of them weren’t actually mass shootings—sometimes a gun was never even fired. In two mass-shooting incidents, an armed security guard or a law enforcement officer, not a civilian, intervened. In two other incidents, armed civilians helped detain a perpetrator after the shooting had already ended, and they didn’t use guns to do so. In five mass shootings, armed civilians tried but failed to stop the attacker—and three of them were shot in the process.

Separate research from the FBI shows similar results. The bureau looked at 160 active-shooter situations from 2000 to 2013 and found only one case where an armed civilian intervened to stop an attack that was underway. (And that civilian was a US Marine.) In 21 cases, an unarmed civilian interrupted the attack and restrained the gunman. In other words, unarmed civilians were far more likely than those with guns to stop an active shooting in progress.

Respond effectively in an active-shooting situation requires extensive training, the Johns Hopkins researchers noted. “There is no reason to believe that college students, faculty and civilian staff will shoot accurately in active shooter situations when they have only passed minimal training requirements for a permit to carry,” they wrote.

Campus carry could lead to more suicides and other gun violence

College students are much less likely to stop a rampage shooter than they are to use firearms to inflict harm on themselves or others, the researchers found. The brains of young adults are still developing, they explain, and that can compromise impulse control and judgment—both of which “are essential for avoiding the circumstances in which firearm access leads to tragedy.” That could be one reason why 19- to 21-year-olds have the highest rate of homicide offenses, according to FBI data. The risk of violent confrontations increases when you throw alcohol and binge-drinking into the mix, the researchers added.

The risk of suicidal behavior, which peaks at age 16, is also high through the mid-20s, the researchers wrote, noting the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and other mental illnesses on college campuses. “Research demonstrates that access to firearms substantially increases suicide risks, especially among adolescents and young adults, as firearms are the most common method of lethal self-harm,” they explained. In one study of 645 college campuses, guns were used in about a third of suicides by male students.

The Johns Hopkins study also broke down gun violence on campuses another way: Of 85 shootings or “undesirable discharges of firearms” on colleges from 2013 to June this year, only 2 percent involved rampage shooters. Much more common were interpersonal arguments that turned into gun violence (45 percent), premeditated attacks on a single person (12 percent), suicides or murder/suicides (12 percent), or unintentional discharges (9 percent).