Since the arrival of COVID-19, our lives have shifted in ways big and small. Most likely, the pandemic will not end with a bang—we’ll be dealing with some version of it for years to come. As we slowly adapt to our new normal, we’ll embrace some changes and resent others. A few of us at Mother Jones wrote about some of the shifts we’ve noticed in our personal lives and the world around us—from the “love it” to the “leave it” to the “we’re still figuring it out.”

Aaron Wiener

This is the year we almost let public transportation die. The cuts that cash-strapped transit agencies proposed before being bailed out by Congress—eliminating 40 percent of New York City’s subway service, a fifth of the DC region’s Metro stations, two-thirds of Atlanta’s bus routes—wouldn’t have been their instant demise, but it was hard to see a way out of the death spiral of mutually reinforcing service cuts and ridership losses.

For white-collar workers tidying up their Zoom backgrounds in their living rooms, the empty tracks were largely conceptual, a hypothetical nuisance in some far-off future that involved getting up off the couch to go to work. But the people running our supermarkets, day cares, and hospitals were already experiencing the very real impact of the deep cuts that had already gone into effect. Lacking other ways to get to work, many of these people—disproportionately Black, Brown, and lower-income—simply left home a lot earlier to endure an extra bus transfer or a longer wait for the train.

Which is all to say that the pandemic has taught us that public transit funding is not just helpful to commuters or vital to a carbon-neutral future. It is a matter of equity. The $30.5 billion for public transit included in the rescue package President Biden signed in March was the biggest subsidy the federal government has ever given our country’s trains and buses. It will get the major urban transit agencies, as well as Amtrak, through the worst of the pandemic-induced dive in ridership. But then they’ll be faced with difficult math all over again, necessitating some combination of higher fares and lower service.

Or not. Other city services aren’t expected to pay for themselves with user fees. When parks or schools or libraries are in need of maintenance, we don’t restrict access to them or charge people more to use them. Instead, we’ve collectively decided that they’re services for the population at large—particularly for those without a golf course membership, private school tuition funds, or a room in the house called the library.

Fortunately, it seems we’re approaching more of a bipartisan consensus on the need for federal transit funding. Biden’s infrastructure plan allocates an additional $85 billion for transit; even the Republican counteroffer includes $61 billion—twice the record-setting amount from the March rescue package. But the country’s public transit systems need steady, dedicated funding to ensure equity, not just infusions of cash in a once-in-a-century pandemic. “This is a grand opportunity,” says Adie Tomer, who runs the Metropolitan Infrastructure Initiative at the Brookings Institution, “to think about a more equitable approach.”

It’s tempting to say that the United States simply can’t hope to have European-style public transit because of our sprawl and car dependence. Yet European and Canadian cities went on the same postwar sprint to suburbanize and build highways; the difference was that they also connected these new suburbs to the urban core by rail. It would be prohibitively expensive to retrofit every US suburb to look like the ones surrounding Munich or Paris. But it wouldn’t be that hard to make them look more like Toronto’s suburbs, which are just as full of cookie-cutter McMansions as many US ones, except they have frequent, reliable bus service. Prior to the pandemic, Toronto’s regional bus service was logging more than 260 million passenger trips annually; in the Dallas–Fort Worth area, which has a bigger population, that figure was only 30 million.

Federal support in the United States has generally been limited to launching fancy new transit projects—say, a light rail that ends up with such a small budget it’s barely useful—rather than maintaining and expanding service on old ones. That money would be better spent making existing bus service widespread and reliable, transit experts say. Buses could not only connect people to the major transit lines heading downtown; they could also link suburbs to one another. That’s vitally important, given that fewer than a quarter of the jobs in major US metros are in the downtown core; 40 percent of commutes are now suburb to suburb. And most jobs effectively require a car, forcing lower-income Americans—who increasingly live in the suburbs—to either stretch their budgets or severely limit their employment options.

“Only buses can effectively deliver anything that looks like equity,” says transit consultant Jarrett Walker. “And yet there’s just been a persistent, relentless disinvestment in their operations.” Walker says he’s often asked to design bus systems on such a meager budget that the buses can only run every 40 minutes. In 2015, Walker helped redesign Houston’s bus network, focusing on providing more frequent service—generally every 15 minutes—in high-ridership areas. With the new map, Houston became one of the few US metro areas with rising bus ridership, though it came at the expense of some service to farther-flung, lower-demand areas.

There’s something for everyone in good public transit. It’s essential to curbing climate change. It’s good business and economics: The American Public Transit Association estimates that every dollar spent on transit generates $5 in economic activity. It makes our urban areas livable and accessible. But the pandemic has highlighted something more fundamental: Many of the people we’ve started calling essential workers simply can’t get by without it.

Madison Pauly

Our criminal court system gives many people who are arrested two choices: stay in jail until trial or put down a certain amount of cash for bail. The latter option, originally intended to ensure defendants would show up to court, has been repeatedly shown to keep low-income defendants and people of color locked up at disproportionate rates, which incentivizes them to plead guilty and leads to harsher sentencing. States and local jurisdictions have been slowly shifting away from money bail for years. But before the pandemic, around two-thirds of the 758,000 people in jail nationwide on any given day still had not been convicted of anything. While a fraction of those had been deemed by a judge to be too risky to release, the majority simply couldn’t afford bail (the median for a felony is about $11,700) or a for-profit bond agent’s fee. Judges set bail amounts and other release conditions using a simple equation: flight risk + future danger to public safety.

The coronavirus changed that calculation. Jenny Carroll, a University of Alabama law professor and former public defender, explained that before COVID-19, the danger to public safety came from a defendant’s supposed chance of committing a future crime. But after the virus turned jails into hotspots, keeping a defendant in crowded jail became a more obvious risk to community safety. “COVID-19 really posed the possibility that for all of us to be safe, it might actually be better if we weren’t detaining as many people,” Carroll says, “if we weren’t keeping as many people in facilities where they couldn’t socially distance, where they couldn’t get access to medical care, where they couldn’t get access to personal hygiene products as readily as in the free world, where hand sanitizer was contraband.”

Some court systems responded accordingly. In March 2020, California’s Judicial Council attempted to reduce jail populations by issuing guidance for judges to set bail at $0 for people booked on misdemeanor or low-level felony charges. Top courts in Alaska, Kentucky, and New Orleans took similar steps. According to a survey conducted by the National Association of Pretrial Service Agencies (programs that analyze defendants’ risk levels to recommend pretrial release conditions), 60 percent of agencies reduced bail amounts in response to COVID, and 68 increased the use of personal recognizance bonds, which don’t require a defendant to pay. Meanwhile, more individual judges started choosing to set lower or no bail, according to Meghan Guevara, executive partner with the Pretrial Justice Institute. “COVID led more judges to exercise the discretion that they have available to them on a daily basis,” Guevara says.

After COVID, judges should continue to exercise that discretion, Guevara argues—but within guidelines that prohibit or reduce the option to impose financial conditions for release. Those kinds of limits could come from legislation like the Illinois law passed in February, which will abolish cash bail in the state entirely and establish a strict process for judicial decisions on whether to lock people up before trial. Following the pandemic, and the national uprising after George Floyd’s murder, Carroll predicts that the national conversation about pretrial release will increasingly center on the ways in which jailing people can harm community safety. “If my father is locked up, I lose the benefit of his company,” Carroll explains. “I lose the benefit of his financial support. I lose some stability. I may lose my house.” All that absence has consequences for community wellbeing.

The question of bail has become more acute since jail populations—which plummeted in the early days of the pandemic—are now rapidly rising, driven in part by court backlogs and police returning to pre-COVID arrest practices. Yet as more people are being booked into jail and come up before judges for pretrial release hearings, questions remain about whether money bail even serves its intended purpose. A study of Philadelphia, where District Attorney Larry Krasner stopped seeking cash bail for many crimes in 2018, found that defendants released without bail were no more likely to skip court or commit subsequent crimes than those who still had bail set. “The theory behind money bail is always, ‘Well, if you have skin in the game, you’re more likely to show up,'” Carroll says. “And when they took away that skin in the game, it didn’t make a difference.”

Ari Berman

During the 2020 election, there was only one early voting location in the town where I live in New York’s Hudson Valley. My wife was determined to vote early to avoid problems on Election Day, but every time she drove by the polling site at the local community center, the line stretched hundreds of people down the hill, with cars parked all along the busy main road. She finally decided to wait in the rain for two hours on the Wednesday before the election.

In contrast, I voted by mail from the comfort of my living room, like so many other Americans in 2020. I didn’t have to stand in the freezing rain, or wait two hours, or worry that I might contract COVID-19 at the polls. Mail voting had previously been highly restrictive in New York—you needed to have a valid excuse, such as being out of town or having an illness that prevented you from going to the polls—under penalty of perjury, to qualify for a mail ballot and then send in a paper application to your county board of elections to receive one. But last September, after these restrictions were waived, I requested my ballot online and cited the pandemic as my reason. I had weeks to research the candidates and make sure I filled everything out correctly, then sent it back in early October, with plenty of time to spare.

The record number of Americans who said they would vote by mail for the first time in 2020 led to widespread fears of an election meltdown. Would President Trump’s efforts to sabotage the United States Postal Service cause hundreds of thousands of ballots to be rejected because election officials didn’t receive them in time? Would voters be disenfranchised because of minor technicalities, like forgetting to sign their ballots or mismatched signatures? Would election officials be able to count so many mail ballots in a timely manner?

One of the major surprises of the 2020 election was how smoothly mail voting went. At least 30 states relaxed their vote-by-mail requirements in response to the pandemic, and the number of Americans who voted by mail more than doubled, from 21 percent in 2016 to 46 percent in 2020, according to the MIT Election Data survey. Though half a million ballots were rejected during the primaries in 2020, when many states struggled to adapt to the rise in mail voting, the number of rejected mail ballots in the general election actually decreased from 2016. And despite Trump’s lies about “vote dumps” for Joe Biden as ballots were slowly counted in states like Michigan and Pennsylvania after Election Day, the 2020 election was judged by Trump’s own administration to be the most secure in US history.

Though the numbers of Americans voting by mail will likely decrease once the pandemic is over, mail voting should be here to stay. Eighty-one percent of people who voted by mail in 2020 said they were likely to do so again in the future, MIT found. The 10 states with the highest voter turnout in 2020 all allowed easy access to mail voting, and five of them sent ballots to all registered voters. When Major League Baseball pulled the All-Star Game out of Atlanta to protest Georgia’s voter suppression law, it was telling that the league moved the game to Colorado, which automatically sends mail ballots to all voters.

Of course, Republicans are doing everything they can to make sure mail voting doesn’t increase in the future. More than half of the anti-voting bills passed by state legislatures this year restrict access to mail voting by giving voters less time to get mail ballots, adding confusing new rules for how to cast them, limiting drop boxes that millions of Americans used in 2020, and preventing election officials from sending out absentee ballot application forms. The moves could backfire on the GOP, since core Republican constituencies, like elderly and rural voters, relied on mail voting before Trump demonized it. The Democrats’ sweeping democracy reform bill, the For the People Act, would stop these efforts by requiring all states to adopt no-excuse absentee voting and mandating access to conveniences like drop boxes, but in June, it was blocked by a Republican filibuster in the Senate.

The 2020 election had the highest turnout in 120 years in part because people had more options to vote than ever before—through the mail, during early voting at the polls, and on Election Day. Despite GOP efforts to make mail voting harder after more Democrats than Republicans used it in 2020, that level of convenience should become the new normal in American politics.

Laura Thompson

Am I the asshole? After a year of scrolling past not-so-socially distanced wedding photos, travel updates, and holiday posts, I finally broke down and purged my social media. I unfollowed hundreds of people—mostly acquaintances from cities I no longer live in—because I simply couldn’t handle the constant surge of anxiety I felt every time I saw one of them dining indoors with a dozen other friends.

Around that same time, a stranger yelled at me for not wearing a mask while walking my dog at the park. It seemed like an overreaction, given that we were outdoors and so far apart that she had to yell for me to hear her, so I kept my mouth shut and spent the rest of my walk stewing in some combination of irritation and shame.

So am I the asshole? Are all of my distant acquaintances assholes? Is the lady from the park an asshole? Yes. Yes to all of the above.

But it’s not entirely our fault.

The public health messaging around COVID-19 has been shaky from the start. First, Americans were told not to worry about the virus; it was just “one person coming in from China.” Next we were advised not to wear masks but banned from spending time outdoors, at places like parks and beaches. For a while we Cloroxed our groceries.

Nationwide, we reversed course on some of those early practices, but the average person’s risk assessment has still grown ever murkier. Some (Republican) governors have ignored CDC recommendations and rushed to reopen their states, threatening local officials who are taking a more measured approach in the process. Around the holidays, some people started giving in to “pandemic fatigue,” deciding that the mental health benefits of visiting long-lost loved ones outweighed the known risks of multi-household gatherings. Now, we’re navigating the vaccine era: Should you get the Johnson & Johnson shot or hold out for a more effective mRNA cocktail? How safe are mixed-vaccine-status gatherings? Can you require proof-of-vaccination for event attendees? How can you possibly enforce outdoor mask requirements only for the unvaccinated?

Without universally agreed-upon best practices being promoted by government officials, Americans were left to fend for themselves and judge their friends accordingly. When I asked Mother Jones readers (and my few remaining friends) whose behavior had been getting to them the most recently, their answers were overwhelmingly virus-related.

Friend held a maskless wedding where they explicitly said to not talk about COVID or you had to put money in a jar….

— Abby Jessen (@abbyjessen) April 14, 2021

Our two next-door neighbours bitching to me about each other about how many people the respective other has over, and “I WOULD NEVER!”. Both entertaining tons more than we do. 🤷🏼♀️

— Menschin (@MenschinDD) April 14, 2021

America has grown increasingly divided in recent years, but the pandemic threw a wrench in relationships in unprecedented ways. r/AmITheAsshole, the reddit channel for airing grievances and voyeuristically consuming strangers’ interpersonal conflicts, put a moratorium on COVID-related posts in March 2020. To paraphrase one of the channel’s moderators: There were too many posts, they were all basically the same, and the comments section could quickly become cesspools of misinformation. Even the online hub for commiserating about shitty friends couldn’t handle the pressure the pandemic has put on relationships.

Countless think pieces have been written about the nature of friendship post-pandemic. Some are cheering the return of casual friendships; others are hoping their social circle stays pared down when everything else returns to normal. My personal wish is a bit more abstract, though. I want to stop thinking about how frequently my friends wash their hands. I want to stop worrying that the Easter brunch hosted by someone from my hometown will be the superspreader event that eventually kills my parents. I want to forget that some of my friends were sharing Plandemic memes. But I’m not sure I can. Global pandemic or not, am I really comfortable sharing finger foods at a Super Bowl party with people who don’t believe in preventative health care?

When I asked my very nonscientific sample of people how likely they were to be able to move past their friends’ perceived transgressions, the answer was generally “Who knows?”

“I don’t think it’s something that will sour [our relationship] permanently, but it does create some hesitancy going forward,” one Mother Jones reader told me.

Only time will tell, I suppose. Some relationships may remain on permanent hiatus, while others may recover after the virus is (hopefully) depoliticized. Inevitably, someone else will do something irritating or downright offensive, and perhaps the memory of your friends’ armchair public health advise will fade. In fact, as the country continues to reopen, we’re in for a return to the rude behaviors of yore: co-workers who steal your clearly labeled leftovers, cousins who bring an uninvited plus-one to weddings, men who manspread on public transit.

Some people will always be assholes, but hopefully anti-maskers and other COVID jerks will soon be a thing of the past.

Andrea Guzman

Over the past year, health care has gone through a digital revolution: As the pandemic intensified, more and more providers switched from in-person visits to telehealth appointments over video chat. In April 2020, telemedicine services increased by more than 4,000 percent, and nearly half of all consultation visits were delivered virtually. For many, this was a welcome change. Virtual visits prevented potential COVID-19 exposure and saved others—especially those in rural areas—from a long commute to the doctor’s office.

The increase in telehealth was driven in part by the public health emergency that went into effect in January 2020. Through it, beginning in March, Medicare was permitted to pay providers the same for virtual visits as in-person ones, and many private insurers followed suit. While the public health emergency has been extended through late July and the Department of Health and Human Services has indicated it will remain through year’s end, keeping these rules permanently would take an act of Congress. Without action, Medicare beneficiaries who have had their virtual care covered could lose it in what some experts have dubbed a “telehealth cliff.”

Take Central City Concern, a nonprofit in Portland that provides services to unhoused people. Last fall, the group set up private suites in their buildings where clients could access telehealth services—like substance abuse recovery and mental health groups—on a donated tablet. Thanks to an emergency order, the virtual appointments were covered by Medicare and Medicaid.

What was meant to be a temporary solution worked surprisingly well, at least once they tackled tech barriers. Jack Keegan, director of nursing at Central City Concern, said some clients relied on their own devices before the suites launched. For people without smartphones or data plans to support these services, virtual care was out of reach before the suites arrived.

Post-pandemic, Keegan predicts many clients will prefer to return to face-to-face services. Yet he says in some cases, virtual visits would make it easier for his clients to access health care. For instance, lack of transportation could stand in the way of someone making their appointment, but that concern goes away with virtual meetings.

Kyle Zebley, director of public policy at the nonprofit American Telehealth Association, watched this play out during the early months of the pandemic. Telehealth “was doing everything that proponents of the industry said it could do, but for a variety of reasons had not been able to do prior to the pandemic.”

In April, lawmakers introduced a bill aimed at saving telehealth. The CONNECT for Health Act was reintroduced by Sen. Brian Schatz (D-Hawaii) and a handful of others. If enacted, it would make COVID-19 telehealth flexibilities permanent and expand coverage of telehealth through Medicare. While it’s died in previous congresses, Zebley said this time around, the fact that half of the senators are co-sponsors is a hopeful sign.

Numerous states have passed or are considering bills to strengthen telehealth access. In Oregon, Central City Concern and the ATA testified in favor of a bill that would reimburse health services delivered via telemedicine at the same rate as a health service delivered in person. In the South, which along with rural communities disproportionately faces challenges to telehealth access, Arkansas passed a law that permanently establishes telemedicine rules that had been put in place during the pandemic.

The pandemic has flipped the switch for patients who had grown accustomed to traditional doctor’s visits, Keegan said. But now that many people have tried out virtual care, some might be reluctant to give it up. “Forcing clients, either because that was all that was offered or because of their own fear in medical spaces, caused them to try a telehealth appointment,” Keegan said. “You’re not going to be able to put that back in the box.”

Sinduja Rangarajan

After an afternoon of play at a park in Oakland, as we were driving back to Fremont, my four-year-old daughter announced that she needed to pee.

We took the nearest exit and parked in a strip mall with a Starbucks. Restrooms were closed. We hit up Quiznos next. No restrooms there, either. Seeing us dash door-to-door, a man asked us if we were looking for restrooms and pointed to a gas station at an adjacent parking lot. “I have kids so I understand the urgency of the situation,” he said.

It would have been a bit much to walk, so we got into our car, strapped our seat belts, and went to the gas station. The guy at the counter said the restrooms at this gas station had been shut since the pandemic started last year.

I had never been madder at another parent.

We asked the guy at the gas station if he knew of a place where our daughter could pee. He pointed to Wendy’s, a two-minute car ride away. We got into our car again. Wendy’s was closed. We saw a McDonald’s nearby. My daughter and I ran inside. We found a clean restroom at last. What a relief.

My biggest beef with McDonald’s in the past has been that it had few vegetarian food choices. But today, I felt grateful, and we celebrated our day without accidents with french fries and some coffee. As my daughter dipped her fries in ketchup, I explained the importance of peeing at home before we leave for someplace.

And yet, when we were on our way to United States Citizenship and Immigration Services today for an important appointment, our daughter said again, “Mom, I need to pee.” It was a tense moment in our car. We were almost at the office, so we went to a gas station nearby. Again, no luck. Restrooms were closed. I knocked on the Dunkin’ Donuts next door. The restroom was out of order.

I could have scurried to a strip mall next door to try Starbucks, Chipotle, or Black Bear Diner, but I didn’t. I won’t tell you what happened next. Did it happen behind a bush? Or did her pants come to her rescue? Did she borrow her baby brother’s diapers for this one time? Did a kind stranger guide us to the right doors this time around? You’ll just have to guess.

Jackie Flynn Mogensen

In early January 2020, weeks before the World Health Organization officially uttered the word “pandemic,” the Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center, a hospital associated with Fudan University, received a sample of a mysterious virus that had sparked a cluster of pneumonia cases more than 400 miles away, in Wuhan. Professor Zhang Yongzhen, a virologist who had sequenced genomes from thousands of new mRNA viruses over the course of his career, quickly got work on this one.

Zhang completed the sequence in under two days, as he recalled in an interview with Time last summer, and submitted his results to a database run by the United States National Institutes of Health for review. But fearing it would take too long for the data to reach people who needed it, Zhang and his team decided to go straight to the public: On January 11, they posted the sequence on the open-access site virological.org.

“That was the most important day in the COVID-19 outbreak,” Linfa Wang, a virologist at Duke-National University of Singapore Medical School, told Nature in December. Thanks to Zhang, the world had a head start on COVID. Even as the virus, which we now know as SARS-CoV-2, began to spread globally, researchers everywhere had already started using Zhang’s sequence to study it, design diagnostic tests, and develop a vaccine. If you’re one of the hundreds of millions of Americans who’ve received a dose of the COVID shot so far, you have Zhang in part to thank for it.

Luckily, Zhang wasn’t alone in recognizing the value of accessible science during this pandemic. Many academic publishers, including big names like Elsevier, Springer Nature, and SAGE lifted their paywalls, which can be pricey, for most COVID-related content. And to meet demand, journals’ speed of peer-review dramatically increased. Meanwhile, new research increasingly published on preprint servers ahead of peer-review and scientists created organic task forces to analyze them. It was like some kind of weird make-believe world where science happened quickly and collaboratively, and research articles were shared on the house. (The system, however, was still not immune to mistakes.) “The pandemic has shown us all in real-time the value and vital importance and role of open science,” Steven Inchcoombe, the chief publishing and solutions officer at Springer Nature, told me in an email, “not just within academia, but for everyone.”

Now, after more than a year derailed by the virus, the case for keeping science open-access—that is, free to readers—couldn’t be any stronger. “If you believe that science matters to solving COVID, then you have to believe that any delays in communicating science would have slowed it down,” says Michael Eisen, editor-in-chief of the journal eLife, a professor of genetics, genomics and development at UC Berkeley, and a co-founder of Public Library of Science (PLOS). Plus, COVID isn’t the only global crisis our planet is facing. What about climate change or cancer or malaria or biodiversity loss or bee colony collapse disorder or coral bleaching? Wouldn’t we benefit from those research articles being freely accessible?

Indeed, advocates have been making this argument for decades, most famously, open-access activist Aaron Swartz, who in 2013 took his life after being arrested for illegally downloading millions of journal articles that he planned to post online. Since then, the calls to free science have grown louder as more researchers acknowledge that the science publishing system makes little sense.

Typically, it works like this: Scientists apply for and are awarded funding, conduct science, and write papers. Then, when they’re ready to publish a paper, they send it to journals one at a time, hoping the most prestigious one will pick it up. Once a journal accepts the paper, it can charge whatever it wants for people to access it. Researchers aren’t paid for their articles—and are expected to review their colleagues’ papers for free as just like, part of the gig of being a scientist. For institutions that rely on research, like universities, access to bundles of journals can cost millions of dollars, even for schools whose own scholars produced some of the work. (It’s sort of like if Mother Jones didn’t pay reporters for their stories, yet charged hundreds of dollars for a subscription.)

The system makes even less sense when you remember that it is often the government—that is, the public—that is funding the research in the first place through federal grants. The other, more obvious problem with this system is that it hinders the cross-pollination of ideas, collaboration, and progress. The data backs me up: According to an analysis by Springer Nature, open-access articles see, on average, four times more downloads, nearly two times more mentions in the media, and 1.6 times more citations—a good indicator of scientific impact—than pay-to-read articles.

It’d be foolish to think all of the industry’s changes will remain after the pandemic. Journals have bills to pay, after all. But from a public opinion perspective, it may be hard for publishers to “put that genie back in the bottle,” says Jeff MacKie-Mason, the university librarian and an economics professor at UC-Berkeley. MacKie-Mason, in fact, has been pushing for more accessible science for the UC system for years as a co-chair of its publisher negotiating team. Back in 2019, UC shook the academic world when it canceled its contract with Elsevier after failing to reach an agreement that would allow free access to the universities’ own research. For two years—including the bulk of this pandemic—the UC staff scraped by. Professors rationed their research needs. They borrowed material through the library system, sourced articles from their peers directly, and relied on preprints. It wasn’t a perfect process and was definitely not sustainable, but it was effective. Just this past March, the UC system got its way and signed a new open-access agreement with Elsevier. According to the university, it is the largest such agreement to date in North America.

The pandemic likely strengthened the universities’ case. “If science is worth anything,” says MacKie-Mason, “the more people who can access it, the better we are,” he says. “The pandemic has proven it.”

Most people I spoke to for this story agreed open access is a win for science. But no one could give me a clear answer about how to actually achieve it. Should the federal government mandate that research it funds be published in open access journals—as many countries in Europe are aiming to do? Should universities foot the bill? Individual researchers? There are a handful of open-access publishers already, like PLOS and the UK’s BioMed Central—but they’re not exactly free. Most open-access journals operate by charging researchers or institutions a fee typically ranging from a few hundred bucks to thousands of dollars to ensure their research is publicly available.

“If we value these things, someone’s going to pay,” says Theodora Bloom, executive editor of The BMJ, a medical journal based in the UK, and a co-founder of preprint server medRxiv. “How do we get to a point where the work is done and paid for, and the results made freely available as soon as possible to as many people? I don’t think we yet know what the right model is.”

Ready or not, there is evidence the science world is already changing. Publishers who designed the paywalls are now vying to lead the open access race. (Inchcoombe told me that since 2015, Springer Nature has published “more [open access] articles than any other publisher,” while Elsevier told me in a statement that it is “the fastest-growing open-access publisher in the world.”) Meanwhile, their competition—journals that are strictly open-access—have skyrocketed in number over the past decade. And universities, like the UC system, are pursuing new, large-scale open-access agreements, including Iowa State, Carnegie Mellon, and the Big Ten, to ensure their research is freely available. “It’s a really rapid movement,” MacKie-Mason says. “There’s been more change in open access publishing in the last five years, I think it’s fair to say, than in the previous 25 years.” I say, let’s keep the momentum going.

Molly Schwartz

For the first time in my life, I understand why so many people who make their livings in front of the camera—reality show personalities, news anchors, movie stars—get plastic surgery. I empathize with them. I get it. I, too, have had the experience of spending an inordinate amount of time looking at myself—not with millions of others on Bravo, but with a select group of colleagues on Zoom.

When I first installed Zoom, I didn’t think too much about the personal implications. As with much of the rest of the world, the pandemic forced my work life online, so I got the tool that allowed me to have meetings and see co-workers while we stayed physically apart. But I could never have imagined how hours and hours of looking at myself would affect me psychologically. I’m someone whose makeup routine takes five minutes max, who doesn’t wear high heels as a matter of principle, and who avoids taking selfies or looking at photos of myself. For most of my life, this hasn’t been a problem.

But slowly, during my Zoom-focused, quarantined life I’ve felt my occasionally ambivalent but generally self-confident sense of my appearance erode. Day in and day out I was forced to stare at the puffy bags under my eyes, the unfortunate spattering of adult acne on my chin, the way my face looks when I laugh too hard (which I usually do). It became impossible not to critically dissect my appearance, to silence my hectoring inner Anna Wintour. After one particularly Zoom-heavy day, I googled eye-lift procedures and how much they cost. (Around $3,000 with a recovery time of two weeks.)

Why not merely select the “hide self” function on Zoom, you might reasonably ask. Because now that I have the option to stare at myself in action, I need to know what everyone else sees my face do. During the pre-pandemic days of uncomplicated indoor dining, when I found myself eating at a restaurant with a mirror on the wall opposite my seat, I couldn’t help checking myself out. It’s too tempting to try to plumb the depths of that impossible question: What do other people see when they see me? And how can I fix it so that what they see looks like I want it to?

Turns out, I’m not alone.

Plastic surgeons are reporting that interest in plastic surgery has markedly increased during the pandemic, especially for the whole menu of facial procedures, from rhinoplasty to face lifts, cheek implants, ear surgery, eye lifts, forehead lifts, neck lifts, botox, and fillers. They’ve even given the phenomenon a name: the “Zoom Boom.”

The market research firm Equation Research surveyed more than 1,000 women across the United States and found that interest in plastic surgery has gone up by 11 percent among women over the last year, though we don’t know the age breakdown. (The absence of men in the survey is glaring—certainly they’re not exempt.) Although almost all cosmetic procedures decreased overall during the pandemic due to office closures, facial procedures decreased by the smallest percentage.

A survey conducted by the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) of their nearly 8,000 members revealed that nose reshaping (352,555 procedures), eyelid surgery (352,112 procedures), and face lifts (234,374 procedures) were the top three cosmetic surgical procedures in 2020. When accounting for the fact that most plastic surgeon were closed for an average of eight weeks in the year, the demand for each of these procedures actually rose by 12 percent, 7 percent, and 4 percent respectively. Demand for the most popular body-focused procedures, by contrast, dropped. Breast augmentation surgeries were down by 18 percent, liposuction was down by 5 percent, tummy tucks were down by 2 percent, and breast lifts were down by 6 percent. During these days spent sitting and staring at the screen, why bother fixing anything from the neck down? (Though demand for butt implants has notably soared!)

I decided to talk to some experts about this—just as a reporter of course. So I tracked down Dr. Lynn Jeffers, a plastic surgeon and chief medical officer at the St. John’s Pleasant Valley Hospital in Camarillo, California, to ask what this Zoom Boom is all about. (Jeffers has also been working overtime running the vaccine rollout at her hospital.) She thinks there are three main factors. People had more disposable income during the pandemic because they were saving money on things like travel and dining out. Also, working from home made recovering from surgery easier and more discreet. And the only factor I could personally relate to: “We were suddenly all on Zoom, and our faces were so big in front of us, and most of us didn’t have great lighting or great webcams and so forth,” says Jeffers. “A number of people attributed the increased interest in facial procedures, as well as Botox and fillers, because that’s what everybody was seeing.”

While Zoom fatigue has been a struggle for many of us, the effects have been especially distressing for the roughly 2 to 3 percent of Americans who struggle with body dysmorphic disorder (BDD). “Skin, nose, lots of different facial features tend to be the focus of concern in BDD,” says Dr. Hilary Weingarden, a practicing psychologist and clinical researcher at Massachusetts General Hospital who specializes in OCD and related disorders, such as BDD. She explained to me that any concerns I might have about my facial appearance can take on a heightened, or even distorted, presence in my self-perception when I see myself on Zoom for long periods of time.

“When you sit on Zoom, you’re staring at them all day long, and so we can tend to over-focus on that body part of concern,” she says. “When we look at ourselves in that way, we can start to actually distort our perception. And it starts to look more blown out of proportion.”

Weingarden points out that when people focus on small flaws about themselves, they are seeing a very different picture from what other people see, which is more holistic. Also, Zoom is a particularly strange and unforgiving vehicle in that it literally lines our faces up next to other faces, which creates a situation that’s ripe for unflattering comparisons—a dangerous rabbit hole, as anyone with a propensity for late-night Instagram scrolling will tell you.

Of course, there are lots of reasons to want to tweak or alter appearance, but my own obsessive dissection of my face just made me feel bad. Self-conscious about laughing or smiling. Deflated by a bad hair day. But more than anything, I’ve felt disappointed in myself that I can be troubled by an issue that is so damn superficial when, yes, I have much to be grateful for. I don’t value other people based on their appearance. Why can’t I extend that same courtesy to myself?

But I think it goes deeper than that. OCD disorders like body dysmorphia have strong ties to anxiety and depression. The obsessive checking and rituals around perceived issues are a channel for anxieties around much bigger things: like the fear of social exclusion, or illness, or dying, or other catastrophic, irreparable calamities—that the pandemic brought to all of our lives to a certain extent. It should be noted that BDD is a severe disorder with high rates of co-morbid depression, high rates of suicidal thoughts and suicidal attempts, and, in severe cases, a paralyzing fear of leaving the house. I do not have OCD or BDD, but I think the ties to anxiety are interesting.

“Most of us have aspects of our physical appearance that we don’t like, that we worry about. And that’s normal to being human,” says Weingarden. “So that experience of worrying about physical appearance, and even engaging in some of these ritual behaviors—we all do some of that to some extent. It can vary anywhere from very mild to full-blown BDD, and everything in between.”

If someone had offered to install a mirror in my computer so that I can stare at myself all day, I never would have agreed to it. Yet somehow that’s what I got. That’s what we’ve all got. Among the innumerable aspects of the pandemic that have been unnatural, add functioning under the constant surveillance of a virtual mirror.

Flow theory posits that people achieve peak performance when they are engrossed in an activity to the point that they lose their sense of self. It’s like being in the zone, or in a groove. For me the best feeling is when my self-awareness fades into the background and I am fully immersed in editing, or reading a good book, or listening to a friend’s story.

When I confided to a friend about my Zoom Appearance Crisis (ZAC!), she pointed out that Narcissus stared at himself all day every day and it didn’t work out so well for him. Sitting at the edge of a lake and engrossed in his own reflection, he ultimately lost all interest in his worldly surroundings and turned into a flower. Clearly, this is not an ideal picture of engagement with the world—much less baseline productivity.

But maybe we got the message from the myth all wrong. Maybe Narcissus didn’t expire because he loved looking at himself. Maybe he just couldn’t look away.

Sinduja Rangarajan

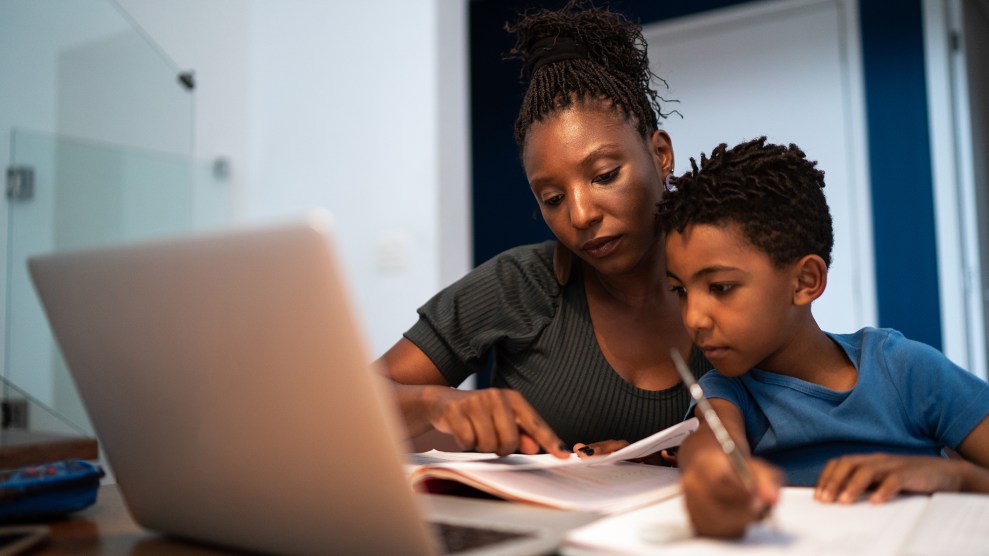

For a large chunk of last year, my then 3-year-old daughter and my husband did what a lot of parents with children did during the pandemic: They wore masks and went out for bike rides in our neighborhood in the evenings.

One evening, my daughter and my husband took an extraordinarily long time to get back. Out of curiosity, I stepped out to see what was up. Our apartment complex had more than 100 condominiums all lined up next to each other. Redwood and Cherry Blossom trees surrounded it, and there was a lot of common space for kids to run and bike around. I walked three times around the area before I called my husband. They were hanging out in a corner that I’d never been to. Under a canopy of trees, my daughter was playing “camp camp” with a neighbor’s daughter. They were collecting twigs and sticks and piling them up in one place. My daughter refused to leave. She’d found her best friend.

Since that day, every evening after we wrapped up work, we’d take my daughter to play outside with her best friend. Soon she found other best friends in the complex. Bike rides were only a ruse. She’d step off the bike the moment she saw any of the kids and start playing. After a day of screens and Zooms, she was eager to see someone her age. I could sense her emotional health improving. She felt lighter and happier after these spontaneous playdates.

This was all happening in April last year when so much about the virus was still unknown. We didn’t know that the virus was less likely to spread through surfaces. We didn’t know that kids were less likely to get seriously infected. We didn’t know that the virus was less contagious outdoors. Still, as parents, we took the risk to let our kid hang outdoors around other mask-wearing kids. We suspended our disbelief about the virus for a few hours every evening. Initially, our conversations with the other parents were awkward and shrouded in anxiety, but still, as our children played, we talked. We shared notes about what each of us was doing to get through the day. We shared homeschooling resources and information about preschool Zoom classes that had popped up. We consoled each other about our little kids learning to “mute” and “unmute” when they barely knew what a computer was. I deluded myself into thinking I was doing this for my daughter, but in the process, I was talking with adults, real people, parents who were struggling to get through the day as I did.

After a few weeks of leaning on each other for support, one of my neighbors said that our community had reminded her of her own childhood in India. I agreed with her. I remember stepping outside my apartment to play with lots of kids in common spaces in our complex as my mom made dinner. Mumbai is an overcrowded city, but one of its virtues is there is no dearth of people around you. And like every big city, it can be harsh and alienating, but to survive it, you need to find pockets of humanity. Remembering my upbringing reminded me of how much my mom invested in building a community around her. Finding people who were accessible was much more important than finding like-minded people with whom you’d like to have a beer. These don’t always have to be at odds, but when you optimize for close geographical proximity, it’s rarer to find someone whose world views exactly match yours.

Before the pandemic, I was commuting three hours to work in San Francisco. My everyday routine consisted of dropping my daughter at a preschool in the morning and in the afternoon dashing through traffic stops and delayed BART rides to make it to the 6:30 p.m. deadline to pick her up. I was completely exhausted by the time we hit the parking lot of our home. There was no bandwidth for taking her out to a park on a weekday. She’d also had her fill of friends and playtime at her daycare.

It wasn’t as if I completely ignored our neighbors before. I knew the names of their dogs and collected their packages when they were away. But during the pandemic, our neighbors became our friends. When the pandemic hit, the lockdown tied us to our geography. Our community is diverse, with people from different age groups, races, and socioeconomic backgrounds. Our next-door neighbors were a family from India. Next to them, some graduate students teamed up together to share an apartment. Next to them, two single moms were raising their children and sharing an apartment. Before the moms moved in, an old disabled man lived with his sister-in-law and brother-in-law from El Salvador, who were taking care of him. In the row of apartments opposite to ours, was an old couple who’d lived there for more than 20 years. Often our mail and deliveries would get mixed up with theirs because our apartment numbers were too similar. When we’d dutifully return the packages; we’d share a thought or two.

Many times during these brief interactions, I got a sense that their beliefs differed from ours. A neighbor commented about how lucky we were that we lived next door to a police station. I’d quietly disagreed but never engaged. Every once in a while, I’d receive the cold shoulder from a group of moms who stayed home with their kids. They’d taunt me about not having the time to invite them for dinner or attend their weekly lunch potlucks.

When the pandemic hit, suddenly, everything that separated us—from our sociopolitical beliefs to our hobbies—became smaller. We were bound together by the universal experience of the pandemic.

The pandemic gave us a way to work through many invisible fault lines. I was better able to relate to moms who stayed home all day taking care of their kids. I was able to even more appreciate the labor that went into child-rearing through the day. Stay-at-home moms in our community were aghast at how much worse it must be for me to hop on office Zoom calls with wailing kids in the background. Even though I couldn’t attend their Tuesday lunch potlucks, I was at least able to meet up with them for a few hours in the evening.

Even if I end up moving away from this apartment complex and even after the pandemic ends, I am going to spend time building a sense of community around me, to find support as I raise kids. This past year has taught me that children playing with other children is the best form of childcare, and neighbors are a low-cost solution to finding support. A community has always been humanity’s answer to survival. I would never agree with some of their viewpoints, and they’d probably never come around to seeing things the way I did, but we all acknowledged that our kids needed a community. We’d found a common language to ground us and build trust. My hope is that our commonalities may open up ways for us to work through other differences and learn from each other.

Art directed and illustrated by Grace Molteni